Author: Atis E Source: medium Translation: Shan Ouba, Jinse Finance

This article looks at the mechanics of CEX/DEX arbitrage trading, focusing on the AMM aspects of execution, aiming to show the relationship between block time, block base fee, and the participants involved in these trades (LPs, Seekers, etc.). It includes simulation results with available source code.

It is widely believed that CEX/DEX arbitrage trading creates a large portion of DEX trading volume, perhaps even the majority of that volume. The Loss and Rebalance (LVR) model1 is a method to quantify and model arbitrage volume from a theoretical perspective.

However, it is susceptible to misinterpretation and misunderstanding. For example, some research papers state (or imply ) the assumption that LP losses on arbitrage trades grow with the square root of block time. This comes from modeling LVR in an idealized setting. However, works that actually run simulations (such as this one ) generally reveal that shorter block times have minimal impact. How can we reconcile these different results and bridge the gap between theory and practice?

Arguably, much of the difference comes from the assumption that arbitrage is a two-person zero-sum game, as is typically modeled in LVR research. However, this assumption is not valid in a post-EIP-1559 world, where transactions cannot be free. Not only does each arbitrage transaction split the profit between searchers, builders, and proposers (SBPs, as mentioned later in this article), it also burns some ETH based on the block space requirements at the time of the arbitrage. To borrow a term from physics, the base fee introduces friction into this process. This friction eliminates a large portion of potential transactions and reduces LPs’ revenue.

1 — Personally, I prefer to call it CVR (Cost and Rebalance) because in real-world DEXs, there is no real entity that accurately quantifies losses through LVR. Instead, a key question that DEX designers and LPs can consider is what percentage of the theoretical LRV they are taking, i.e. what part of the LVR is actually the expected loss of LPs in a model where the DEX is only used by arbitrage traders. That said, I will stick to LVR in this article to avoid more confusion.

Price Action Examples

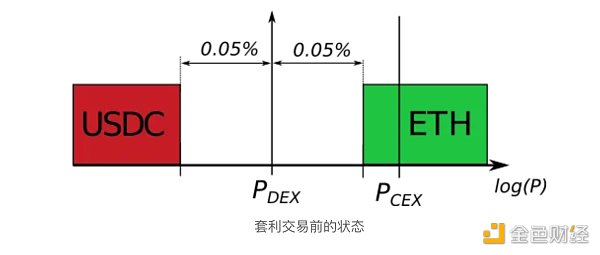

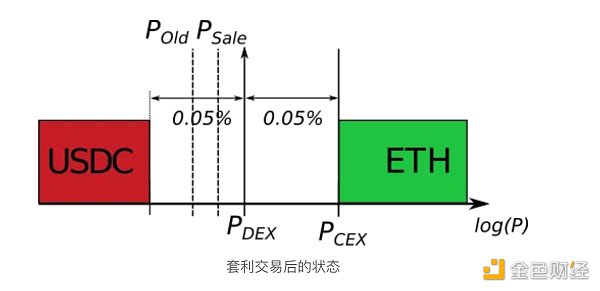

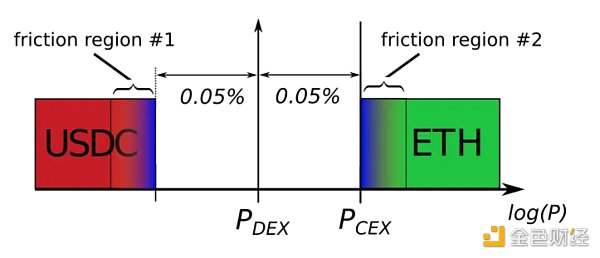

Let’s look at the arbitrage mechanism in detail. The following figure shows a typical state in a DEX pool after the price on the CEX changes enough to attract arbitrage.

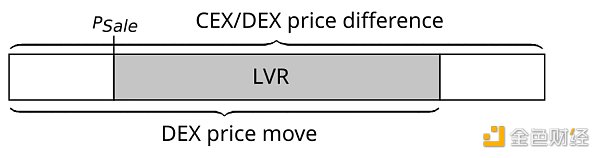

The following figure depicts the state after the arbitrage transaction. The DEX price has transformed from P_Old to P_DEX, and the LP sells its assets at the P_Sale price, which represents the geometric mean between the two prices. The new DEX price is still slightly deviated from the CEX price, but it is still in the non-arbitrage area. Therefore, unless the CEX price rises slightly or falls sharply to completely cross the non-arbitrage threshold and then some, no further transactions will occur.

What happens if the CEX price now goes up by 0.001%? The trade will not happen. This is because, on both sides of the non-arbitrage gap caused by the mining pool exchange fees, there is a friction zone caused by the blockchain's base fees and other factors, including CEX fees (if any), priority fees and bribes to block proposers, arbitrageurs' prediction accuracy and risk tolerance, etc.

For the purposes of this article, we assume that the block base fee creates the majority of friction, and ignore other factors. The friction created by the base fee is predictable to arbitrageurs, and they are unlikely to create any swaps where the expected profit after subtracting the expected base fee of the next block is negative.

Single transaction LVR analysis

When the difference between the CEX and DEX quotes is large enough to exceed the pool's swap rate, an arbitrage trade is triggered. But the LVR achieved by a single arbitrage trade is not proportional to the spread. Instead, the LVR is proportional to the difference between the trade execution prices on the CEX and DEX. Assume that the CEX trade execution price is equal to the quote, but the DEX trade execution price is P_Sale , which is the geometric mean of the quotes before and after the trade.

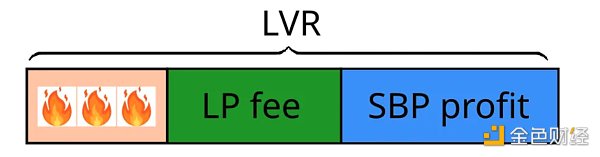

In addition, a single transaction LVR is distributed among three entities:

Liquidity Provider

Searchers, Block Builders, and Block Proposers (SBPs) as a collective entity

ETH holders, affected by ETH destroyed in transactions

LPs receive swap fees, while SBPs collect arbitrage profits, which are then distributed among these three participants. It is not surprising that comprehensive searcher-builders dominate the arbitrage market , as they have to deal with a simplified version of the principal-agent problem in profit distribution.

ETH holders are not directly compensated, but the value of their ETH will increase slightly over the long term due to deflationary pressure.

High volatility increases the likelihood of price increases, which increases carry trades. In addition, it makes the expected jumps larger. LP fees are often uncorrelated with volatility, leading to unfair distributions to LPs when volatility rises.

By comparing the LVR of a single transaction and the LP fee of that transaction, we can evaluate the fairness of that transaction to LPs. In the case of a smooth price evolution without jumps, the LP fee can almost recover the LVR, and the LP loss is small. However, if the DEX to CEX spread fluctuates due to block time granularity or actual price discontinuity on CEX, the LP fee will be less than the LVR, resulting in some losses for the LP for this (theoretical) rebalancing strategy.

Example scenario

Let’s model the in-scope liquidity of the Uniswap v3 ETH/USDC 0.05% pool. As of April 2024, it holds ~$1 billion worth of virtual assets, equivalent to ~$150 million in physical assets, with a liquidity concentration of 6. Having deep liquidity is critical if we want to be able to arbitrage swaps even on relatively small price changes.

A simple Uniswap v3 swap might consume around 150,000 gas , equating to a USD cost of $10 per swap, assuming a reasonable 22 gwei base fee cost and a $3,000 ETH/USDC price. During times of DeFi stress and high volatility, costs can easily increase several times.

Example 1

Assume that the starting price of ETH on both CEX and DEX is $3,000.

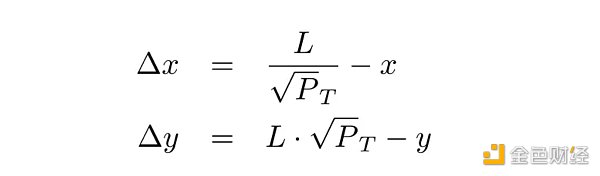

First, let's see what happens when the CEX price changes by +0.1%. The current CEX price is $3003, which is outside the non-arbitrage zone. The arbitrageur calculates the DEX target price P_T , which is equal to 3003 · 0.9995 due to the 0.05% fee charged by the mining pool, and swaps part of the USDC for ETH on the DEX, raising the DEX price to the target price. The swap amount is defined by the liquidity L in the pool and the (virtual) reserves x and y :

This will return the amount without fees, to get the input amount including fees the result must be divided by 0.9995 (for a 0.05% pool).

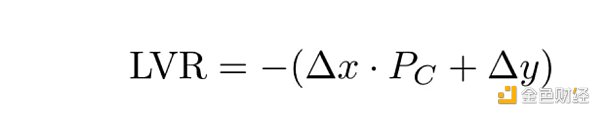

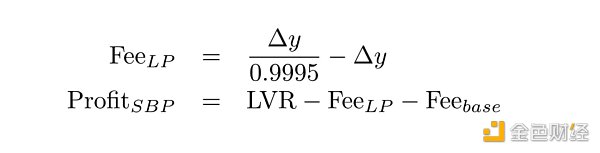

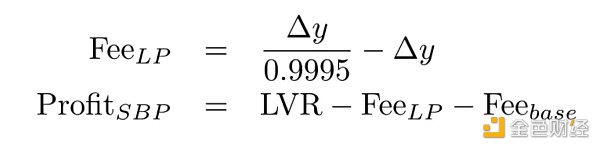

LVR is calculated based on delta and CEX price P_C :

The LVR is then divided into an LP fee portion, an SBP profit portion, and a block base fee, which does not depend on the details of the transaction except for its Gas cost:

If the estimated SBP profit is positive, the transaction may take place, otherwise it will not.

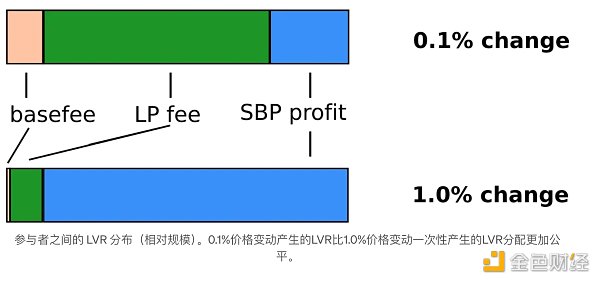

For the example pool with $1B worth of virtual assets, the swap’s LVR is $93.66 and the LP fee is $62.46, resulting in 33.3% of the theoretical single-transaction LVR being realized as LP losses. About a third of the loss comes from the $10 block base fee.

Example 2

Keep the same assumptions, but let the CEX price change by 1%.

In this case, the LPs did receive an impressive fee of $1,184.66. However, the LVR per trade grew much faster, reaching $12,406.47, meaning that the LP losses accounted for 90% of the theoretical LVR.

This shows that LP losses are super-linear with price changes. The price increased 10x (0.1% vs 1.0%), but LP losses increased over 360x ($31.19 vs $11,221.81).

Example 3

As can be seen from the previous examples, limited partners are better off if they can trade incrementally rather than all at once.

Let us consider a short block world where the price changes by +0.1% twice (i.e. from $3000 to $3003 and then to $3006), and a long block world where the price changes by +0.2% once.

The LP fee is $187.39, which is the same in both cases. (These trades are path-independent because we assume non-compounding fees.) However, the LVR is higher in the second one.

Specifically:

For short blocks, the cumulative LVR is $343 and the LP loss is 45.4%.

For long blocks, the cumulative LVR is $468 and the LP loss is 60.0%.

Example 4

Finally, let's consider the example of oscillating prices. First, the price changes by -0.1%, then increases to +0.2% from the starting price. In the short block world, the LP is able to trade both times, while in the long block world, the LP cannot trade the price drop and its reversal because they both occur within a block.

turn out:

For short blocks, the cumulative LVR is $843, the LP fee is $312, and the LP loss is 63.0%.

For long blocks, the cumulative LVR is $248, the LP fee is $187, and the LP loss is 60.0%.

This example shows that LVR is a counterintuitive metric. In the short block world, the pool has much higher transaction volume and collects correspondingly higher fees. Moreover, the final price is the same, so the Impermanent Loss is equal in both worlds. However, in the longer block world, the realized LVR, as well as the LP loss quantified by the LVR, is higher.

Example Summary

Summarizing the results:

If prices can be modeled as a GBM process, then overall both models suggest that a short block world may be preferable.

If prices follow some other pattern, such as fluctuating around the mean, then shorter blocks will lead to worse outcomes according to the LVR model.

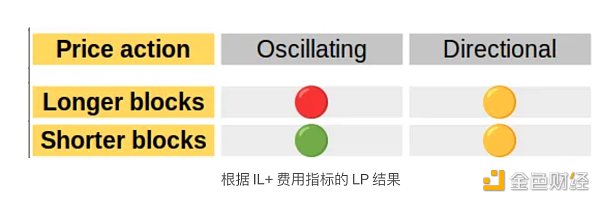

The LP results are summarized in the figure above.

It’s worth emphasizing that using Impermanent Loss+ fees as a metric yields very different results from the LP perspective:

However, we know that for volatile pairs that follow the GBM assumptions, the IL and LVR based models should eventually converge to the same result, since the expected value of the LVR is equal to the expected value of the IL. We need to go beyond the specific cases analyzed so far. See the next section!

Simulation study

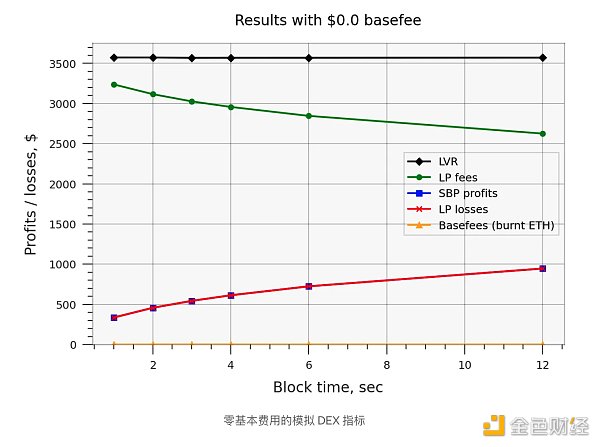

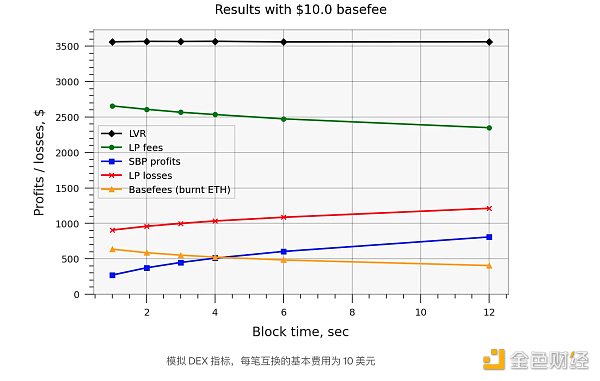

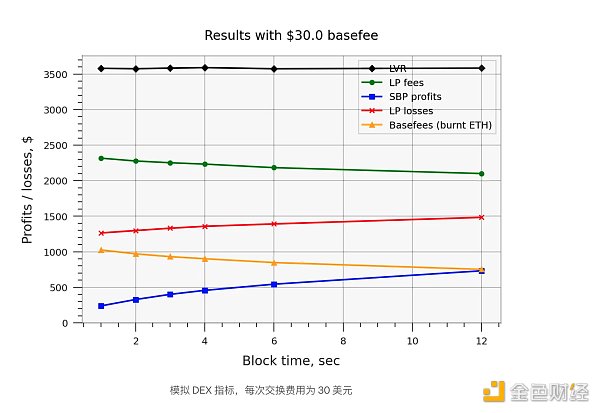

The following figure shows the DEX performance metrics simulated using a stochastic GBM. The simulation assumes an annual volatility of 50%, which corresponds to a daily volatility of about 2.6% for a 12-second block and a volatility of 0.03% per block. This is roughly how ETH has fluctuated in recent years.

The simulation ran for 3600 seconds and by coincidence the LVR was approximately $1 per second or $3600 per hour². LP losses ranged from $350 to $900 per hour ($3-8 million per year). To be clear, this theoretical model does not include any LP fees from noise/uninformed traders, whose LVR is expected to be zero, compensating for LP losses on arbitrage trades.

The results show that when the basefee is zero, LP losses can indeed be modeled exactly by the function sqrt(blocktime) + const (i.e. not by its square root, since there is some offset from the x- axis even for short blocks) . However, after we introduce the EIP-1559 basefee into the model, this result no longer holds, since more frequent transactions also consume more ETH, offsetting most of the positive effect on LP fees - see the results below. Furthermore, and more importantly, the basefee costs increase by a constant offset from the x- axis.

² — Due to the settings chosen for the simulation, the results can be used as a rough and likely highly inaccurate approximation of the Uniswap v3 USDC/WETH 0.05% pool on mainnet. Analyzing the matches and identifying the biggest reasons for the discrepancy between the empirical performance could be a subject of further research.

Summarize the results

Generalizing to other pools. Simulation results are specific to the USDC/ETH 0.05% pool, which is typically the most liquid volatility pool on Uniswap v3. For pools with lower liquidity, the importance of friction caused by the base fee will increase. For example, assume that the ETH/USDT 0.05% pool has 1/3 of the liquidity. Then the results for this pool with a $10 base fee will match the results for the USDC/ETH pool with a $30 base fee. Friction will similarly decrease for pools with higher liquidity, such as USDC/USDT and other stablecoin pairs.

Generalization to other chains. The model assumes that shorter blocks simply divide the available block space differently, rather than adding more block space. If the reduction in block time was accompanied by a proportional reduction in basefee, the simulation results would not be generalizable and would look very different.

Replicating theoretical results

(This is a more technical section that most readers can skip.) While my simulations are not guaranteed to be accurate, they can be compared to the results of the paper “ Automated Market Making and Arbitrage Profits in the Presence of Fees ”. There are two main differences in the setup/assumptions between the different works:

The paper assumes that transactions are frictionless—there are no base fees or other costs for arbitrageurs.

The paper assumes that block times are Poisson distributed.

Rather than redesigning the DEX simulation to incorporate non-uniform block times, I designed a separate function for a “fast” simulation that only calculates the probability of a transaction per block, rather than other metrics. The results are very consistent with the paper:

When the function is changed to use uniform block times, the results are slightly different, but not dramatically so. The results of the full DEX simulation match the quick simulation fairly well, giving confidence that it is implemented correctly. (Or at least, with the same assumptions):

However, when adding a non-zero basefee, the positive impact of shorter block times is greatly reduced:

Impact on blockchain design

The “LP Loss” curve in the DEX Performance Metrics graph above clearly shows that LP losses do not actually increase in proportion to the square root of block time, unless the base fee is zero. This is not a novel or unexpected finding, but simply reiterates the principle that more frequent transactions lead to higher transaction costs. However, given that the sqrt time model has become a common assumption, it may benefit from wider dissemination.

Pick only one significant result that conflicts with this hypothesis: According to the simulation results, it is best

Providing liquidity in a 30 bps pool on-chain with a 120 second block time,

Rather than for

Providing liquidity in a 5 bps pool on-chain with a 2 second block time

If the base fee for the trade equals $10, the relative losses for the LPs are 26.9% and 31.3%, respectively. In the real world, a 5bp pool could certainly be better, but only if there is enough volume from noisy/uninformed traders.

While shorter blocks do benefit LPs, the impact is limited and less significant than other factors (base fees, liquidity depth, pool fee tiers, and other potential factors). A more compelling argument for fast block times may come from the perspective of traders — as faster confirmations improve the trading user experience — or from other participants, such as smaller block builders, who will have more opportunities to win proposer auctions in a short block environment. However, shorter block times also come with significant centralization risks : increased network bandwidth and latency requirements for network validators; increased processing requirements; greater importance of geographic proximity; and an overall design bias toward HFT. Needless to say, the existence of alternatives could reshape the entire debate depending on how it evolves — such as moving to L2; adding pre-confirmations to L1; or others.

Therefore, we can divide the block time design problem into two parts:

L1 perspective: A decentralized, trusted neutral design is absolutely necessary for Ethereum and other L1 blockchains that aim to compete with Ethereum. No matter how important they are, they should not be over-optimized for the performance of a single application.

L2/Appchain Perspective: In contrast, L2s or Appchains do not need to tailor their designs for general-purpose applications. L2 fees may already be low enough to reduce the friction caused by the base fee to negligible levels. If this is not the case, then paradoxically, exempting CEX/DEX arbitrage swaps from the EIP-1559 base fee will benefit DEX users.

Summary

in conclusion:

Due to the EIP-1559 base fee and other factors, arbitrage trading is not frictionless.

Therefore, the theoretical LVR in the real-world DEX is divided into three entities: LP, ETH stakers, and SBP as a collective entity.

A more gradual price change results in a more equitable distribution of LVRs among the three entities.

On chains with higher transaction costs, changing block times will only slightly increase LP profits relative to other factors.