Welcome to the 193 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last week! If you haven’t subscribed, join 230,390 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Contrary

If you like deep dives on great startups, then do I have the job for you!

Contrary, a venture firm that has backed companies like Ramp, Anduril, and Zepto, is hiring a Research Analyst for Contrary Research to build on their efforts to create the best starting place to understand any private company. The role is fully remote with competitive salary and more. If interested, email research@contrary.com and mention Not Boring!

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Tuesday! Fun week.

Today’s Deep Dive is a long time coming. Last year, when Julia DeWahl and I hosted our season of Age of Miracles, we got to speak with a lot of the founders building nuclear startups. Only one founder turned us down: Radiant’s Doug Bernauer. Radiant was heads down racing to a 2026 deadline and wasn’t spending much time talking about the company publicly. Respect.

Earlier this year, though, on a trip out to Los Angeles, I got to meet Doug and some of the Radiant team at their El Segundo HQ, and see a little bit of what they were building up close. That’s when Doug first told me about why he started Radiant — because Mars needs nuclear — and when I knew that I had to write about the company.

Today is my daughter Maya’s 2nd birthday — happy birthday, Maya! If Radiant succeeds, she and Dev might get to celebrate a birthday on Mars one day. What a world.

So this is a Deep Dive on Radiant, and on what it takes to build a nuclear reactor from scratch on Earth so that one day we can use it to power a civilization on Mars.

Let’s get to it.

Radiant

(Click here to read the full thing online)

SpaceX takes its mission “to make humanity multiplanetary” completely seriously.

“When Musk launched SpaceX back in 2002, he conceived it as an endeavor to get humanity to Mars,” Walter Isaacson wrote in Elon Musk, “Every week, amid all the technical meetings on engine and rocket design, he held one otherworldly meeting called ‘Mars Colonizer.’ There he imagined what a Mars colony would look like and how it should be governed.”

Elon’s former Chief of Staff, Sam Teller, recalled a 2014 SpaceX board meeting on the same theme: “They’re sitting around seriously discussing plans to build a city on Mars and what people will wear there,” Teller later marveled, “and everyone’s just acting like this is a totally normal conversation.”

On the surface, it seems absurd. In 2014, the Starship rocket that might one day carry humans to the Red Planet was nine years away from its first testflight. Starlink, which would fund the journey to Mars, was still five years away. And the first successful landing of a Falcon 9 first stage, the reusability that would make the whole thing possible in the first place, wouldn’t happen for another year and a half. But here was the board, spending precious meeting time debating Martian fashion.

Your first reaction might be that Elon is weird, and he is the boss, and so everyone humors him. His former assistant, Elissa Butterfield, told Isaacson, “We tried to avoid ever skipping Mars Colonizer, because that was the most fun meeting for him and put him in a good mood.”

But it wasn’t just Elon.

Doug Bernauer, an eleven-year SpaceX veteran, gave up a salary, stock options, and the enviable position as a senior jack-of-all-trades engineer at the world’s most ambitious company to fix an existential problem he helped uncover, simulated, solved for, and presented to Elon and the team in a Mars Colonizer meeting.

Here was the problem: to colonize Mars, you need to send Starship up with supplies, then refuel it and send it back to Earth, all without humans, because untamed Mars is too risky, and the food to feed them weighs too much.

But how do you refuel Starship on a planet with no fuel?

It’s actually possible. You can vaporize the ice that’s all over Mars into water, run it through an Electrolyzer to split H2O into Hydrogen and Oxygen, pull CO2 from the atmosphere, then react Hydrogen and CO2 using the Sabatier reaction to produce methane. Then compress it, cool it to a liquid, fill the tanks, and keep it cool with cryo coolers. The challenge is: that takes a whole lot of power.

Turns out, you would need over three football fields worth of solar panels to produce all of that power. Assuming that you could get the panels spread out on Mars’ surface, a task for which the team looked at a number of unorthodox solutions, you’d also need to send up vehicles that could anchor them into Mars’ rocky surface. All told, the mass of the panels plus all of the other machines involved in the process would require two missions.

Solar was a no-go. But not powering Mars was not an option, either. What to do?

In a meeting with Tom Mueller, now the CEO of Impulse Space, and Elon, Doug remembers, “Elon said the word nuclear first.”

SpaceX had no nuclear division. Unlike solar, Elon didn’t have a nuclear company on the side. The company had no nuclear code, nothing on the topic except for a few studies that Mueller, already a big nuclear fan, had done.

Doug didn’t know anything about nuclear, either, but he knew how to figure things out. In his time at SpaceX, he’d already worked on everything from mining locomotives to space lasers. So he raised his hand to study the problem, and in doing so, changed the trajectory of his career.

Nuclear on Mars

At first blush, the idea of building nuclear reactors on Mars seems like a fantasy, and a potentially wasteful one at that. The age-old knock against the space program is that we shouldn’t be spending tens of billions of dollars sending rockets to faraway planets when we have so many issues left to solve right here on our own.

The counters to that line of thinking are manifold, ranging from the aspirational to the practical.

On the aspirational side, humans need a frontier, a just-out-of-reach goal to strive towards. Plus, making humanity multiplanetary is an insurance policy on the most valuable thing in the universe.

More practically, the things we develop for space directly improve life on earth.

GPS is the most obvious example. Without satellites, your Google Maps wouldn’t work. But the list of products you use in your daily life that were born out of or improved by space research is shockingly long: cell phone cameras, memory foam, scratch-resistant lenses, cordless tools, water filtration systems, infrared ear thermometers, joysticks, LASIK, artificial limbs, cochlear implants, insulin pumps, soft contact lenses, and baby formula, to name a few. When I finished the London Marathon in April, I was quickly wrapped in a reflective blanket of the sort first developed by NASA in 1964.

And as Brian Potter highlights in his series on solar, at a time when solar PV electricity was 5x more expensive than batteries and 10,000 more expensive than electricity from utilities, satellites “would be the main customer for solar PV for the next 20 years,” kicking off the technology’s earth-altering descent down the cost curve.

That such a disproportionate amount of innovation would come from space research is counterintuitive but logical.

In Taste for Makers, Paul Graham wrote that difficulty can lead to good design:

When you have to climb a mountain you toss everything unnecessary out of your pack. And so an architect who has to build on a difficult site, or a small budget, will find that he is forced to produce an elegant design.

Space is harder than a mountain: it is extreme, remote, resource-constrained, and unforgiving. Governments, and private companies, are willing to pay large sums of money for solutions, often with indefinite payback periods, in a sort of Pascal’s Wager: that the ultimate gains will be near-infinitely large.

Researching for space gives geniuses permission to treat seemingly fantastical ideas with life-or-death seriousness, with extreme constraints that strip away any considerations except the hard facts, which is exactly what Doug did when he began studying nuclear on Mars.

The first question he asked was: could nuclear achieve SpaceX’s objectives on Mars?

He started reading papers and playing around in Python, comparing solar versus nuclear. Pretty soon, he realized that nuclear had a number of advantages.

For one thing, you could fit everything – the nuclear reactor, the Sabatier reactor, and all supporting machines, in one Starship.

Instead of needing to land at the equator, where the sun is, the Starship could land at Mars’ North Pole, where the ice is.

If you landed right on the ice, you could integrate a reactor right into the rocket, use the heat it produces to melt a hole, let it freeze back up over the hoses, and end up with a giant well. This is very similar to a process that humans have undertaken in the Arctic and Antarctic for decades – a Rodriguez Well, or Rodwell. The first Rodwell, built at Camp Century in Greenland, just 800 miles from the North Pole, in 1958, actually drew its power from a nuclear reactor. In October 2020, four years after Doug had the idea, NASA actually studied the potential of using Rodwells on Mars, and concluded that it could potentially work, although more studies are needed.

When Doug concluded his study, he had his answer: nuclear could achieve SpaceX’s objectives on Mars. And he had his self-assigned marching orders: “OK, after we build Starship, this is the thing to do and build,” he said, “This is the mission statement.”

Remember, SpaceX people are dead serious about building a civilization on Mars. Elon takes time out of his insane schedule every week for Mars Colonizer. Doug, realizing that humans would have to farm on Mars and that he didn’t know how to farm, ripped the grass out of his family’s front yard and started planting wheat with his kids to practice.

Just getting a rocket to Mars isn’t enough.

To form a society up there, you need power, and more specifically, you need nuclear power.

By that logic, then, figuring out how to build nuclear reactors that you can put in a Starship and send hurtling through more than 100 million miles of space, became a problem of civilizational importance, and one that Doug would be willing to spend the rest of his career solving.

He remained at SpaceX for the next three years, getting smarter on nuclear, reading papers and playing with simulations at night while doing his day job during the day, waiting for the time when he and the team would hit go on their nuclear plans.

Then in January 2019, the Department of Defense’s Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO) announced Project Pele and requested “the development of a safe, mobile and advanced nuclear microreactor to support a variety of Department of Defense missions, such as generating power for remote operating bases.”

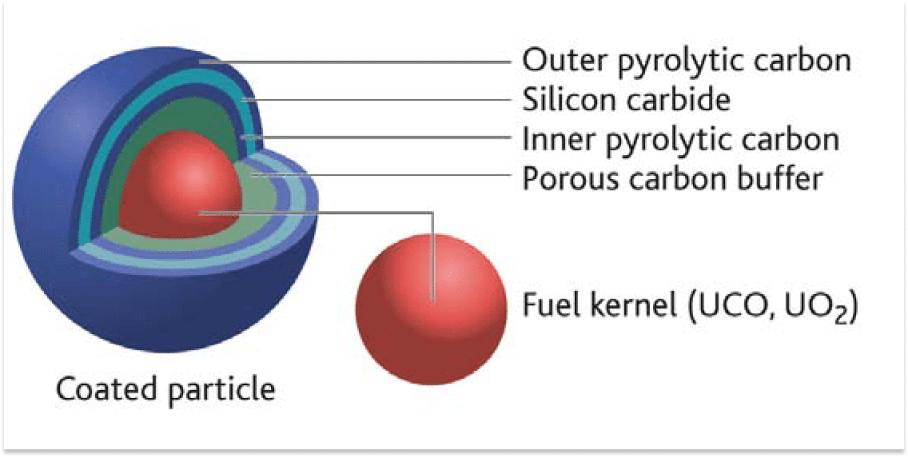

The DoD had very specific needs: a 1-5 MW high-temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGR) mobile nuclear reactor that could be transported in a C17 to be set up quickly in remote locations, that used High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) fuel in damage-resistant TRISO (TRIstructural-ISOtropic) fuel particles, which could be run for several years without refueling and use passive safety systems that can shut down safely on their own.

Project Pele was a loud, clanging siren for Doug. He knew that the DoD must have put out the request with a supplier in mind – the Defense Science Board reviewed many companies three years prior to creating the program to ensure its specs were reasonable and that the RFP would generate sufficient replies – but he thought that SpaceX should compete anyway.

Nuclear was too important to the plan, and no new reactors had been built in such a long time. Having the DoD behind the project could change that. It could solve all of nuclear’s challenges – funding, customer, and regulatory – within one entity, which meant that the time was right for some company to be the company that built a new reactor.

He thought that company should be SpaceX, and tried to set up a nuclear team within the friendly confines of the space giant. Meanwhile, since the DoD had requested proposals, he went on sabbatical to temporarily go full-time on the project, pulling together an informal crack team that included Firmware Engineer Bob Urberger, to submit one. The team came up with a name – Radiant – and a logo, and even set up a legal entity through which they submitted the proposal.

The team didn’t win the proposal, nor did Doug win his attempt to set up a nuclear team within SpaceX. It was just too hard for a big company that had so many other complex things going on.

That was fine. The proposal had confirmed to him that he couldn’t work on anything but solving this problem, so in 2019, Doug left SpaceX to found Radiant.

Simulating Radiant

Now that hard tech is undergoing a SpaceX-driven renaissance, there’s a belief that a founder can simply leave SpaceX, raise his or her hand, and receive millions of venture dollars to build the SpaceX for X.

That was not Doug’s experience founding Radiant.

When he hung up his shingle, Doug’s sum total of experience with nuclear power was that one project. He understood the rough shape of what he would need to build – something close to Project Pele’s requirements – but he didn’t know what the reactor design would be, how to design a reactor, or anyone who knew how to design a reactor.

He set out to remedy those issues in reverse order.

First, he started reaching out to people in the nuclear industry on LinkedIn, and was met with a surprisingly positive reception. This is something I’ve heard from a number of nuclear founders – industry veterans are extremely welcoming to fresh talent. One of the suggestions he heard over and over again in those conversations was to go to the annual American Nuclear Society event to meet more people, so Doug, Bob, and a few others went at the end of 2019. They met more people, including Jess Gehin, the Associate Laboratory Director, Nuclear Science & Technology, at Idaho National Lab (INL).

In early 2020, on Gehin’s invitation, Doug visited INL, where he walked on top of reactors talking about different technology types. “I fiendishly learned everything I could about fuel, densities, costs,” he said, all information that he would bring into figuring out how to design a reactor.

Second, he set out to learn reactor design through simulations. He’d figured out how to do the necessary modeling work for the proposal he submitted while at SpaceX (via Radiant Industries), but by his own admission, what they submitted was “really a Frankenstein, not a good design from an expert.” So he turned himself into an expert.

Then, early in Radiant’s life, before the company had raised any money, COVID hit. Like many of us, Doug spent much of his lockdown glued to his computer. Unlike many of us, Doug was using his computer to model nuclear reactors.

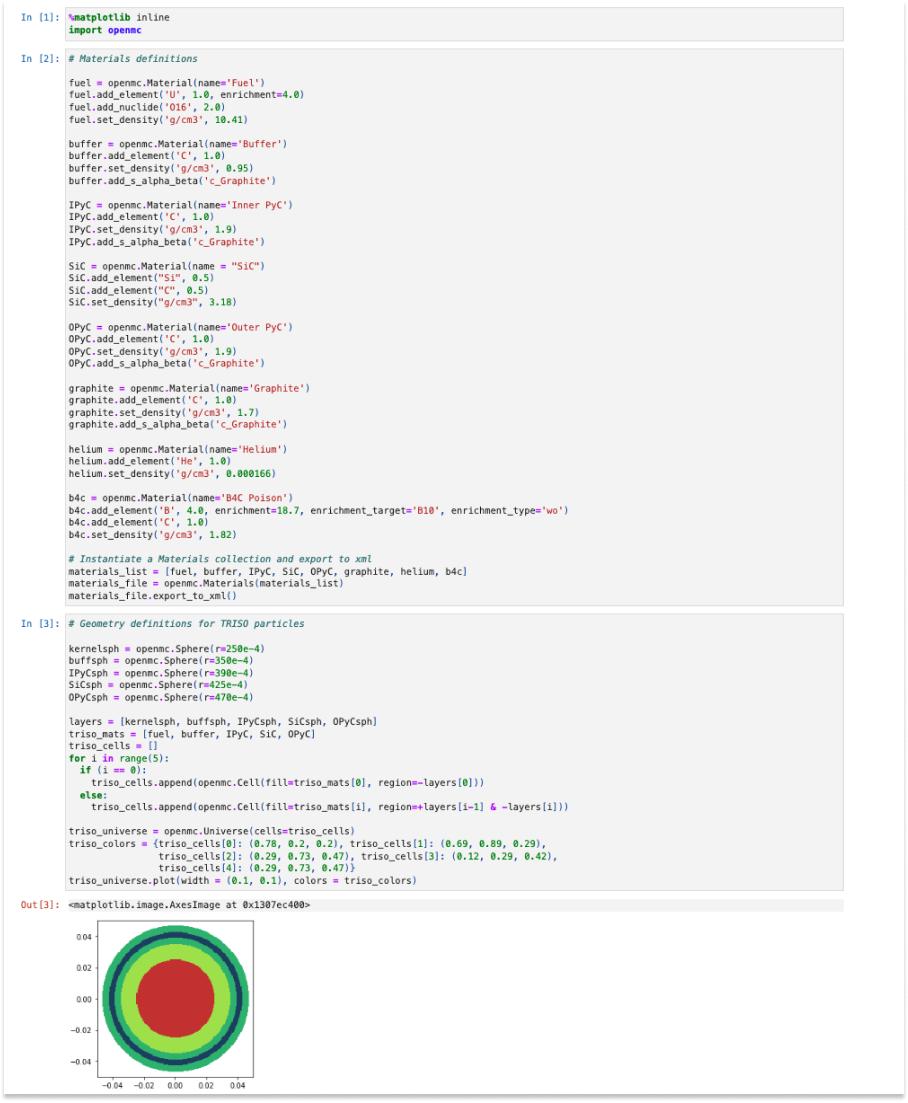

Taking what he’d learned from conversations, questions, and papers, Doug started running simulations in code, first using a program called Serpent, “a multi-purpose three-dimensional continuous-energy neutron and photon transport code, developed at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland since 2004,” and then a more modern one called OpenMC.

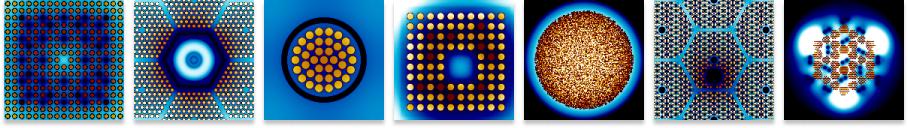

This is what some OpenMC code looks like for a Very High Temperature Reactor (VHTR):

In OpenMC, you can adjust a number of different parameters, like fuel enrichment or coolant channel sizes, and the Monte Carlo code simulates a number of particles by making neutrons, picking a random direction for them to head, and rolling the dice on their starting energies. It outputs metrics that tell you how the simulated reactor performs, like k-effective.

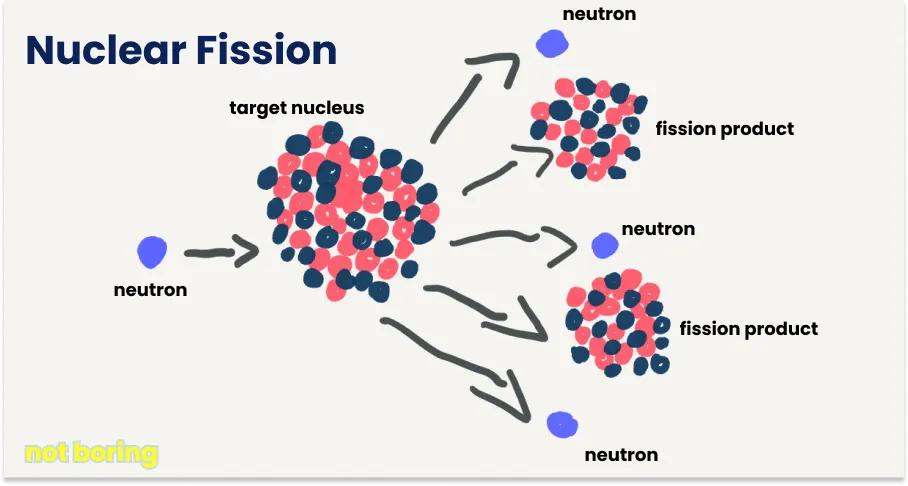

K-effective is the ratio of the number of neutrons in one generation to the number of neutrons in the previous generation in a nuclear fission chain reaction. As Doug explained, “If you get 2.4 neutrons from every fission reaction, and lose 1.4 neutrons, and 1 gets back to fission, that’s critical.” Meaning, each reaction produces a certain number of neutrons. Some are lost to any number of factors, like absorption in non-fissile materials, leakage from the reactor core, parasitic capture in U-238 (you want it to hit the U-235 isotope, not U-238), or absorption in control rods). If just one neutron survives to set off fission in the next U-235 atom, and so on, then the reaction can sustain and produce power.

There are dozens of parameters and dozens of output metrics in OpenMC, and in an actual nuclear reactor. Change one parameter, and all of the outputs change. It’s a multivariate problem with no right answer; it depends what you’re solving for. In Doug’s case, he was solving for a reactor that roughly hit Project Pele’s request, but even within that limited design space, there are practically limitless permutations.

Luckily, Doug had a lot of time. He ran hundreds and hundreds of simulations, first to get a feel for how different decisions influenced the output, the way you or I might play with a model’s sensitivity to different inputs in Excel in order to understand a business. He’d share each new batch of runs with his new friends at INL and a particularly helpful professor at UC Berkeley. That professor, he said, enjoyed seeing the frenzied attempts of a novice but SpaceX-credentialed outsider.

Once Doug got far enough down the rabbit hole on a certain design, tracking metrics and responsiveness to tweaks the whole time, he’d throw it all away and start fresh.

“I didn’t know what the hell I was doing,” he smiled, but with each fresh model, he knew a little bit more.

Third and finally, Doug got to a reactor design he liked: a 1 MW High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor that uses a hydride moderator inside of a graphite core to lower fuel requirements.

Typically, fuel costs aren’t a huge consideration in nuclear reactors. For a 1 GW reactor, like the Westinghouse AP 1000, nuclear fuel makes up something like 5-7% of the total cost of operating the reactor, unlike something like an oil or gas plant, in which fuel is by far the biggest cost because you need to keep feeding it in to produce electricity. But for Radiant’s smaller reactor, 0.1% the size of a utility-scale reactor, fuel is a huge percentage of the overall cost, as high as 40-60%.

This is where the nuclear modeling bleeds into financial modeling. With a rough outline of the reactor design, Doug began to dig into the economics. Costs for various inputs to a nuclear reactor, like fuel, were actually harder to find than Doug expected. Luckily, there are contracts through federally funded programs that are mandated to be publicly available, so he’d get one number, and even if it was hard to corroborate, he’d go with it for the time being.

As Doug learned at SpaceX, iteration speed is everything. The perfect is the enemy of the good.

“Take it, look at it, run with it. Don’t wait, ever.”

He didn’t. While working on the reactor design, he was talking to manufacturers about the helium pumps they’d need to cool it. He lined up partners with nuclear-grade experience. He kept meeting people. Hired Armand Eliassen, a longtime Naval Reactors engineer. Bob Urberger joined the team full-time as a co-founder. They hadn’t raised any money yet, but Doug and Bob put in some of their own to say, “This is now a thing.”

Then in late 2020, the DOE announced its Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program (ARDP), initially with $160 million from the DOE, and then with another $2.5 billion funded by the Infrastructure bill, to back up to ten projects. The program would award grants in three pathways:

Advanced Reactor Demonstrations

Risk Reduction for Future Demonstrations

Advanced Reactor Concepts 2020 (ARC 20)

The first pathway funded two existing companies – Bill Gates’ TerraPower and X-Energy – to support “design, licensing, construction, and operation” of those companies’ first reactors.

The other two pathways, however, were wide open. Five or six companies had tried and failed. This was Radiant’s first big shot.

Demonstrating Reactors on Earth

I realize I haven’t stated this explicitly yet, so for the avoidance of doubt: while Doug’s plan was to develop nuclear reactors for use on Mars, Radiant was created to start by designing nuclear reactors that work on Earth, reactors that could attract capital and make money on earth.

Even SpaceX, with the world’s best rockets and well-laid plans for Martian dominion, funds those things by selling telecommunications services to terrestrial customers.

And to make a nuclear reactor that makes money on earth takes money, which the DOE was offering.

So Doug, Bob, and Armand got to work on putting together their proposal. “We had a month or two to put the whole thing together,” Doug remembered. “It was a forcing function.”

The proposal required a design and cost estimates for the reactor, which the team had already been working on, but it also required a funding schedule: how much money would the team need, and when, to build its reactor.

More specifically: how much would it take to get to the DOME in 2026 with a fueled reactor test?

Remember this. Four years ago, the Radiant team committed to having a reactor ready to fuel up and test at the National Reactor Innovation Center’s Demonstration of Microreactor Experiments (NRIC-DOME) test bed at Idaho National Laboratory by 2026. Hold onto that thought.

More urgently, the team calculated that it would only need $2.8 million to fund its development in the first year, which the DOE ARDP could cover, if they won. They’d need money in the interim, though, so for the first time, Radiant went out to raise money.

Again, in 2024, that would be easy. That would be the tiniest round an ex-SpaceX founder building in nuclear could convince an investor to shrink down to. In 2020, though, it was another story. Radiant raised $700k from angels, and Doug pitched VCs on the story that this DOE program was coming, and that they thought they could win it. VCs replied: “Cool, we will put such and such a check in when you win it.” Doug had to sell more SpaceX stock to fund the company while it submitted, and then awaited the results of, its proposal.

So they submitted. And then they waited, and waited, and waited, for three or four months, until one morning, Doug said, “I woke up, looked at my phone all foggy-eyed, saw the email, and it was like, ‘Nah.’”

Radiant did not win the award, or the money that came with it, or the money that VCs promised to wire the company once they won it.

“Everything they wrote in the rejection was true,” Doug told me. “But it was just the negative aspects, none of the positives. ‘You have no past performance record,’ ‘you haven’t worked in nuclear.’ It’s silly stuff when you look at it now, totally true but the totally wrong way to look at it.”

Ultimately, though, the company was able to raise the money it needed on SAFEs from three investors – Acequia Capital, Also Capital, and Boost VC. And more importantly, they had a design, a budget, a goal, and a plan to get there: DOME in 2026 or bust.

Why the DOME Matters

To understand why the DOME is so important to Radiant, you need to understand a little bit about the history of nuclear energy in America and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s (NRC) chicken-and-egg approach to regulation.

Back in the first Atomic Age, after the US dropped nuclear bombs on Japan, there was tremendous excitement around using that same newfound capability that humans had gained, the ability to release huge amounts of energy by splitting atoms, for good.

In 1953, President Eisenhower addressed the United Nations General Assembly to deliver what would come to be known as the “Atoms for Peace” speech.

President Eisenhower imagined that, “if the entire body of the world's scientists and engineers had adequate amounts of fissionable material with which to test and develop their ideas, this capability would rapidly be transformed into universal, efficient, and economic usage.”

They did, and it was. On Age of Miracles, nuclear engineer and author of the excellent whatisnuclear.com Nick Touran told me and Julia DeWahl that the period was a time of incredible experimentation in nuclear power:

There was a time back in the 40s, 50s, 60s, where there were a hundred thousand people around the world, the smartest people in the world, all focused on nuclear reactor technology. It was like The Thing. And so there's so much interesting information and history and things that people did back then. It just blows my mind. Every time I go, look, I find something new. We had lots of small reactors, dozens of small reactors, some of which pretty much check all the boxes of the things that we're excited about now. We actually built them.

People were experimenting with all sorts of nuclear reactor designs, using various moderators, coolants, vessels, and sizes. There were Light Water Reactors, both Pressurized and Boiling, Heavy Water Reactors, Gas-Cooled Reactors, Liquid Metal Fast Breeder Reactors, Molten Salt Reactors, Organic-cooled Reactors, Homogeneous Reactors, and Graphite-Moderated Reactors, among others. As Nick pointed out, a lot of the reactor designs startups are excited about today were first tested way back in the ‘50s and ‘60s (many such cases in hard tech).

If the phrases “nuclear reactor” and “experimentation” sound odd together, well, it was a different time. Back then, nuclear reactors were governed by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which was tasked with both regulating and promoting/developing nuclear technology. The AEC of course cared about safety, but it didn’t care only about safety. It believed that nuclear power was a force for good and regulated it as such.

Then a couple of things happened, one market-driven and one-government driven.

On the market side, the US Navy, under Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, decided to use Pressurized Water Reactors (PWRs), built by Westinghouse, to power nuclear submarines. Westinghouse used this experience to create commercial PWR designs, and as more utilities embraced nuclear, and engineers realized the economies of scale present in larger reactors, the US nuclear industry essentially just made bigger and bigger PWRs.

If you’re picturing a nuclear plant in your head right now, with the hourglass-ish cooling tower, you’re probably picturing a PWR. Sixty-three of the ninety-four active nuclear reactors in the US today are PWRs, and the other thirty-one are the similar Boiling Water Reactors (BWRs).

This explains why the US coalesced around Light Water Reactors back then, but none of it explains why the DOME is so important to Radiant today. That’s the government-driven piece.

In 1974, Congress passed the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, which split the AEC’s responsibilities into two organizations:

The Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA) took over the research and development aspects of nuclear energy, as well as other energy-related programs. This became part of the newly-formed Department of Energy (DOE) in 1977.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) was given the responsibility for the regulation of civilian nuclear power and nuclear materials.

At the same time, the DoD’s nuclear programs – including the Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program – were separated from the civilian agencies, meaning that money spent on the defense side wouldn’t fund the peaceful use of nuclear energy, practically the polar opposite of Eisenhower’s vision of Atoms for Peace.

That decision, although it may not have been the intention at the time, set the nuclear industry in amber as it existed in 1974. In the 50 years since the NRC took over, it has never certified an advanced nuclear reactor (non-water cooled) design. The NRC has also not licensed the construction of any new reactor design, including LWRs. Despite the fact that we need clean energy. Despite the fact that many of the new designs are safer than water-cooled designs!

That’s an embarrassment, full stop.

Peeking inside of the embarrassment, part of the problem is the NRC’s chicken-and-egg approach to regulation that I mentioned earlier: the NRC wants to see data proving that a particular reactor design is safe, but it won’t allow companies to test their reactors in order to generate that data! That’s so maddening to even type that it’s a small miracle any entrepreneur is willing to build a nuclear startup.

But entrepreneurs are clever and resilient, and many are taking novel approaches to getting around the NRC’s roadblocks. And one path around the roadblocks is to test a reactor in one of the DOE’s national labs, like, for example, Idaho National Lab.

Contra the NRC, the DOE is awesome. It’s quite literally the good half of the AEC. I talked about some of the great work it does on things like fusion and nuclear safety in my deep dive on Fuse Energy, and it also provides loans and grants to fund the development of new energy technologies, and provides facilities to test advanced reactor designs. Like the DOME.

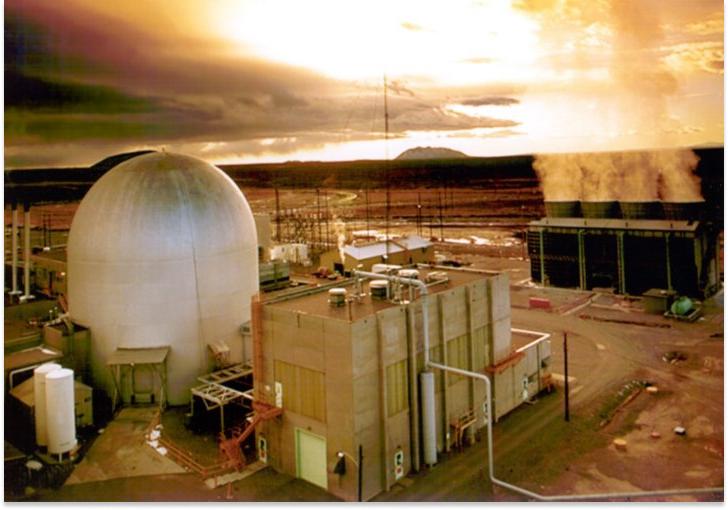

The “DOME” at INL, officially known as the Contained Test Facility, was built to house the Experimental Breeder Reactor II (EBR-II), a breeder reactor power plant built and operated by Argonne National Laboratory back in the AEC-overseen good ol’ days 1964.

EBR-II was shut down in 1994, and the decades-long decommissioning process began. In the 2010s, there were plans to take down the large concrete dome from which the facility takes its nickname. Contractors actually cut a giant vertical slit in the dome (lowercase, the actual structure) to begin the process. The DOME was on its way out until, miraculously, passionate leadership at INL’s Materials and Fuels Complex got those plans changed in 2018.

Now, INL is preparing the dome to serve as a test facility for advanced reactors. The refurbished Demonstration of Microreactor Experiments (DOME) test bed is set to open in 2026.

Hence Doug’s original plan to test at the DOME in 2026. Hence the race to the DOME.

Here’s the logic more succinctly. Currently, there’s nowhere to test an advanced nuclear reactor design, hence there’s no way to generate the data the NRC needs to see to approve a design, hence there’s no way to get a new design approved. When the DOME begins operations, hopefully in 2026, it will be that place, the facility at which nuclear startups may be able to resolve the NRC’s chicken-and-egg paradox. Whichever company can test in the DOME first has a timing advantage: it can get the data, get NRC approval, and roll out commercial reactors before anyone else.

Here’s Radiant’s logic. If humanity is to be multiplanetary, we need nuclear reactors on Mars. To make nuclear reactors for Mars, you need to make a nuclear reactor that works on earth. To make a nuclear reactor that works on earth, you need money. To make money, you need to mass produce nuclear reactors on earth and sell power from those nuclear reactors to customers who need it at a price they can afford. To do that, you need approval to make nuclear reactors. To do that, you need data. To do that, you need to test in the DOME.

Because the reactor design Radiant is pursuing is not water-cooled, and nothing like it has ever been approved by the NRC before.

Meet Kaleidos

Now is as good a time as any to tell you more about the reactor that Radiant is building. They call it Kaleidos.

If you want to skip this section, you can. We’ll cover what the reactor design enables in a little bit. As a little teaser, check out Radiant’s website. When I talked to Union Square Ventures’ Fred Wilson, an early Radiant investor, he said, “Make sure to point people to their website.”

But I think one of the most important things to understand about Techno-Industrials is how the technology and business model fit together, so if you’re willing to dig in with me, I promise you’ll at least learn a little bit about how nuclear reactors work and the trade-offs that nuclear companies need to make. On y va.

Recall that Doug and the Radiant team wanted to design their reactor to meet Project Pele’s requirements: “a safe, mobile and advanced nuclear microreactor,” and more specifically, a 1-5 MW high-temperature gas-cooled (HTGR) mobile nuclear reactor that could be transported in a C17 to be set up quickly in remote locations, that used High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium HALEU fuel in TRISO fuel particles, which could be run for several years without refueling and use passive safety systems that can shut down safely on their own.

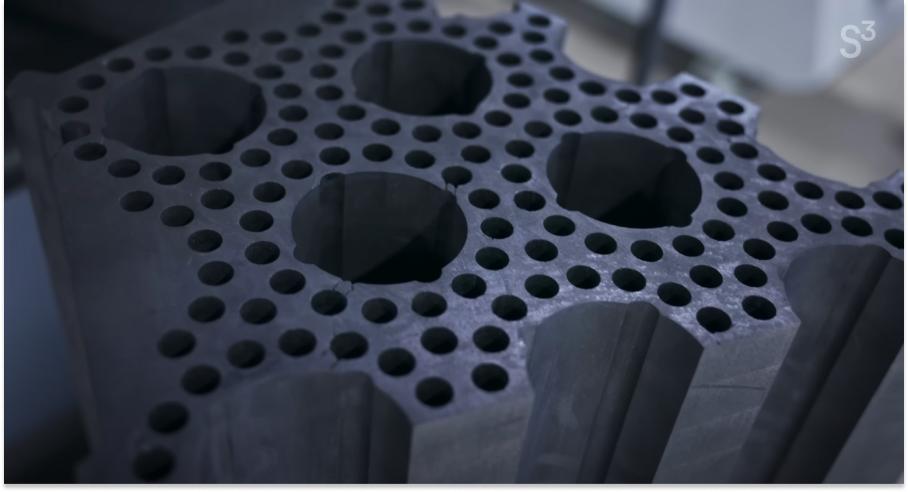

That’s what they’ve done. I’ll break it down piece by piece, but I also highly suggest watching the episode that Jason Carman did on Radiant for S3, and I’ve linked to the part where they talk about how the reactor works:

Or watching this in-depth four minute video on Kaleidos:

For the text version, we’ll go over the three main variables: size, fuel, and coolant.

Size

To start, Kaleidos is much smaller than the nuclear reactors you’re thinking about. Those are typically 1 gigawatt (GW), enough to power roughly one million homes. Kaleidos is 1 megawatt (MW), enough to power roughly one thousand homes.

That, as Doug points out, is a practically entirely different product, three orders of magnitude (OOMs) smaller than a standard reactor. Typically, reactors are broken out by OOM:

Normal: 1000 MW, or 1 GW

Small Modular Reactor: 100 MW

Microreactor: 10 MW

Kaleidos is an OOM smaller than that, at just 1 MW. “Three OOMs is like taking a plane that fits 200 people and a remote controlled plane,” Doug pointed out, “and regulating them the same way.”

But that’s how they’re regulated. Thanks, NRC. (This is hopefully changing with the passage of the ADVANCE Act and the NRC’s Part 53 regulation, which is being developed to create a specific regulatory framework for advanced nuclear reactors.) You’ve got to play the game on the field.

Being small means that Kaleidos can fit in a plane or on the back of a truck to be shipped to remote locations that desperately need clean, consistent power. It also implies a number of design choices and trade-offs.

Fuel

For one thing, a smaller reactor means that fuel becomes a large percentage of the overall cost of the system, as high as 40-60% versus 5-7% in a gigawatt-scale reactor. Aside from the cost, the HALEU fuel in TRISO pellets that Radiant plans to use is hard to come by. Fuel is probably the biggest supply chain risk to any nuclear startup.

On the fuel itself, Radiant will use High-Assay Low-Enrichment Uranium fuel at the high-end of the “low-enrichment” range with an enrichment level of almost 20% uranium-235 (the rest is mainly uranium-238, which is not fissile).

That choice ties into the Pele specs, but it also aligns with Radiant’s business model. Higher enrichment allows for more efficient fuel use because with more U-235 atoms present, there's a higher probability of neutrons causing fission rather than being absorbed by U-238 or other materials. Remember, you need one neutron to make it to the next U-235 atom to go critical.

HALEU can also achieve higher burnup rates – the amount of energy extracted from the fuel – before required refueling. This is particularly important given the fact that Kaleidos will operate in remote environments where a longer time between refuelings has a dramatic impact on unit economics. Radiant’s reactors will go five years between refuelings.

The HALEU fuel will be encapsulated in TRISO pellets, which the DOE calls The Most Robust Nuclear Fuel on Earth.

TRISO fuel is meltdown-proof and can handle temperatures up to 1,600°C. Radiant’s reactor will have about 100 million of these poppy seed-sized particles.

As mentioned earlier, though, that 100 million number is lower than it could have been, because Radiant designed the core with both a more traditional graphite moderator plus a hydride moderator.

Radiant makes its core out of graphite, as seen in the image above. The image of the core is from an old design; you can see some small defects, which they’ve learned from and corrected in current versions. The current design is made up of 37 sections, which Radiant calls “monoliths,” which are narrower than the wedge shown above. In both new and old designs, those smaller holes are where it puts the TRISO fuel pellets. The bigger holes are coolant channels – helium flows through them to pick up heat – but Radiant also puts hydrides in there. I’ll explain why.

We talked about fission reactions earlier. Neutrons hit the heavy U-235 atoms in the fuel, causing them to split and release both energy, in the form of heat, and more neutrons, which continue the chain reaction.

These neutrons zoom around at high speeds. The higher the speed, the less likely they are to produce another fission reaction. The role of moderators is to slow the neutrons down and increase the probability of more fission reactions. The physics are way more complicated than this – and over my head – but roughly, the better the moderation, the less fuel you need, since moderators increase the likelihood of fission reactions.

Light water reactors, like all of the gigawatt-scale reactors in the United States, use good old H2O as both their moderator and their coolant, which has advantages in terms of simplicity, efficiency, and safety. Some advanced, or “Gen IV,” reactors don’t use moderators at all – these “Fast Reactors” keep neutrons fast and trade lower fission of U-235 for the fact that high-energy (fast) neutrons can actually cause fission in U-238. Many of the reactors that use slowed-down (thermal) neutrons, like Radiant, use graphite as the moderator that slows them down.

Hydrides – like YH1.7 and ZrH1.6 – have higher hydrogen densities than graphite, which makes them very effective moderators. Doug’s early insight was that by also using hydrides as moderators, they could use less fuel by increasing the probability of fission reactions more than with graphite alone.

There is no free lunch. Hydrides are more expensive than graphite and require more careful engineering. In a larger reactor, where fuel cost and supply is less of a concern, hydrides might not make sense. And even Radiant isn’t using a fully hydride core; it’s mainly graphite. But given the reactor size, Doug realized that using some hydrides as moderators would bring down the overall cost of the system.

OK, let’s zoom back out. All of that – the HALEU TRISO fuel, the moderators, the fission reactions – the point of all of that is to produce heat, which can be converted to electricity (and potentially used to heat water).

How that heat is transformed into electricity comes down to the coolant.

Coolant

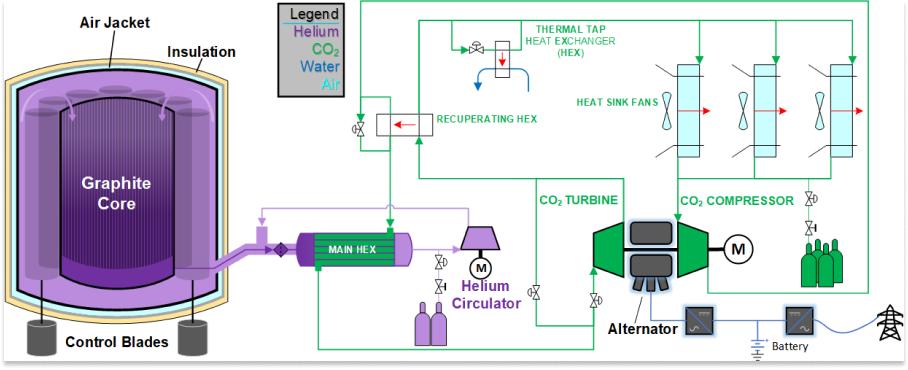

Per the requirement, Kaleidos is not a light water reactor, but a high-temperature gas-cooled reactor. In this case, the gas is helium. Helium serves as the coolant. Here’s how it works:

Nuclear fission reactions heat several tons of graphite.

Helium is continuously cycled through the reactor in a closed loop.

Cool helium enters the reactor core at lower temperatures and picks up heat from the graphite (the reactions themselves produce energy as heat).

The helium heats up to about 700°C as it leaves the core and flows to a heat exchanger.

In the heat exchanger, the hot helium heats up supercritical CO2 (sCO2).

The hot sCO2 drives a turbine alternator compressor to generate electricity using a closed Brayton cycle.

The sCO2 is further cooled in the heat sinks and sent back to the heat exchanger.

After transferring its heat, the helium is forced by an electrically-driven turbopump to flow back to the reactor to pick up heat and go through the process again.

With me? Good.

Helium has some unique attributes that make it potentially safer than the water used in light water reactors, chief among them that helium doesn’t become radioactive as it’s bombarded with neutrons from the nuclear reaction. Helium-4, the most common isotope and the one Radiant uses, is supremely tight and stable: it’s just two protons and two neutrons. That gives it an extremely low neutron capture cross-section, meaning that when neutrons hit the helium atoms, they’re much more likely to scatter than to be absorbed.

All of that to say, if, on the off chance, a Kaleidos suffers an incident and releases its coolant into the atmosphere, it would just harmlessly float away. There would be no radioactive fallout.

That’s important for any reactor, but it’s particularly important for smaller reactors that will be located in remote locations across the globe.

The combination of a helium primary coolant and supercritical CO2 power generation loop keeps Kaleidos safe in accident scenarios while also efficiently converting heat to electricity.

Doug told me that Radiant’s current design currently achieves “30% average thermal to electric conversion.” Large nuclear reactors typically have about 33-37% efficiency, so 30% is very good for a much smaller system. That said, Doug mentioned that they could potentially increase it to 42% with design improvements in later generations, and that their approach has a 49% efficiency ceiling at Kaleidos’ scale.

As with anything in reactor design, getting there would come with trade-offs, and the Radiant team will continue to look at those trade-offs as they evolve.

So there you have it. Kaleidos is a 1 MW reactor that uses HALEU TRISO fuel, graphite and hydride moderators, helium coolant, and a Brayton cycle involving sCO2 in order to deliver a compact, mobile, efficient, and affordable product to customers that can go five years between refuelings.

That leaves us with one Pele requirement: passive safety systems that can shut down safely on their own.

While each of the decisions we’ve discussed are designed to optimize for economics, they’re also designed to optimize for safety. TRISO is meltdown-proof. Helium is non-radioactive. 1 MW is small enough that even without those features, a meltdown wouldn’t be catastrophic.

In addition to all of those physics-based passive safety features, Radiant – Bob, in particular – has built a “Digital Twin” of the reactor, a systems model of the nuclear reactor to model its safety in various scenarios.

When I went out to visit Radiant’s El Segundo HQ in February, Bob let me play with it. You can do something like, say, click a button to disable the heat sink and model out what happens to the reactor. In the coming months, as it builds out the full reactor (without the nuclear fuel, for now), it will tie real sensor data from the reactor into the Digital Twin to make real predictions.

As Bob said in the S3 video, “The idea here is that we can demonstrate the shutdown profile of the reactor system in the case of an emergency, and show that as the nuclear fuel continues to produce heat, that we remain passively safe.”

Ultimately, nuclear reactors generally are way safer than people think, and Radiant’s reactor specifically is way safer than that.

So how does all of that tie into Radiant’s business? Is this the best approach to nuclear?

Trick question.

Understanding the Nuclear Startup Market

Typically, when looking at investing in startups, I’m looking to find the one company that will win a large market. Power laws are a hell of a drug, as Anduril/Founders Fund’s Trae Stephens lays out well in Venture Capital’s Space for Sheep, and typically there’s one power law winner per category.

Through that lens, you may be tempted to look at the nuclear power startup landscape as a competition among all of them, with one really big winner eventually emerging.

I think that’s the wrong way to look at nuclear, for a couple of related reasons.

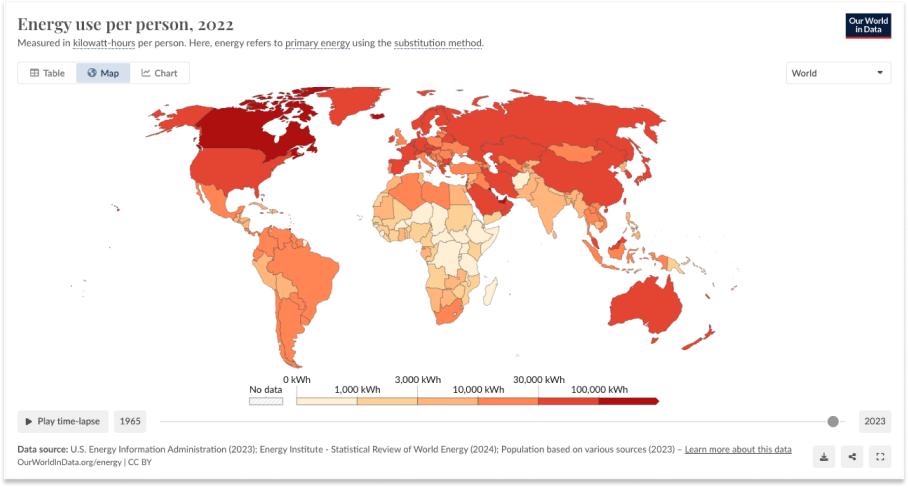

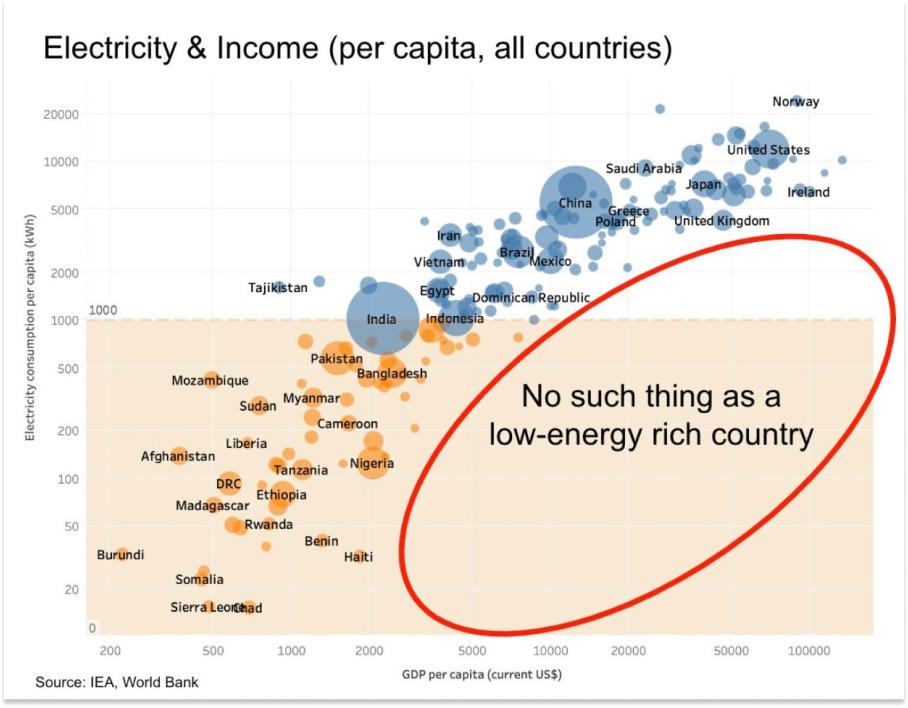

First, energy is just such a massive market that it can produce a lot of winners. According to a recent International Energy Agency (IEA) report, consumers around the world spent $10 trillion on energy in 2022 before accounting for government subsidies, and the vast majority of the world’s population doesn’t consume as much energy as they could or should. India’s 1.4 billion people, for example, consume 10% the kilowatt-hours of their American counterparts.

Even Americans don’t consume as much energy as we can or should. There is no more direct input to GDP per capita than energy consumption per capita. As the meme goes, there is “No such thing as a low-energy rich country.”

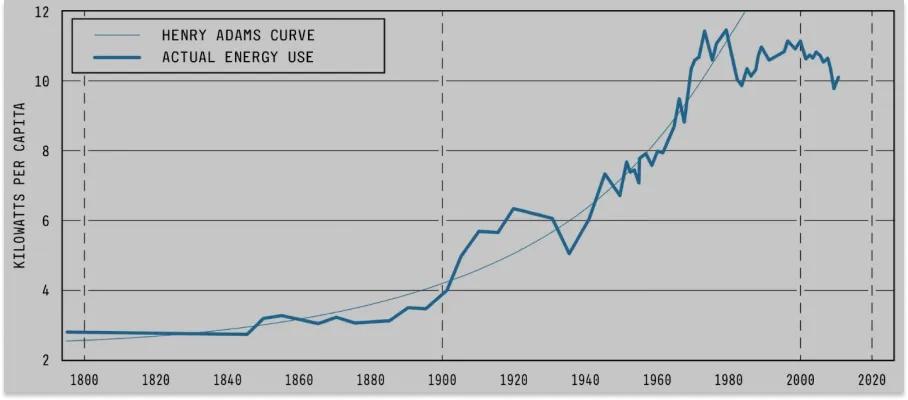

America today will not look rich by this standard to our grandchildren. Our growth in energy consumption fell off a cliff, or more specifically off the Henry Adams Curve, in the 1970s.

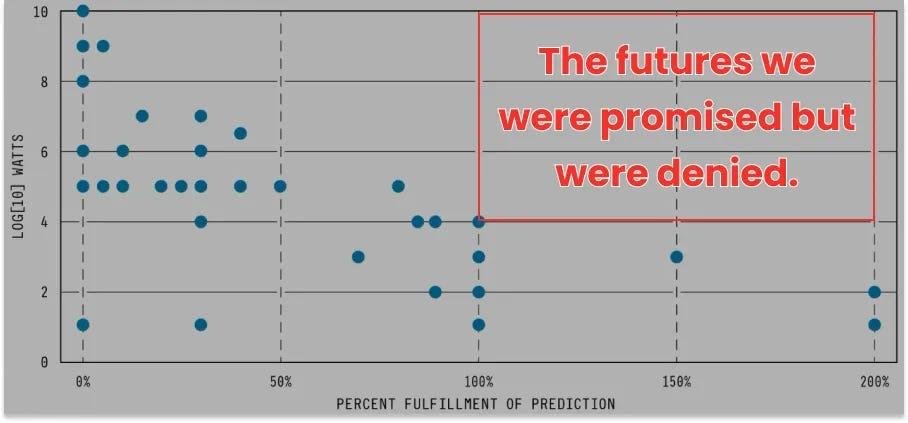

In Where is My Flying Car?, J. Storrs Hall argues that this is why, while many of the sci-fi predictions in the digital world did come true, none of those predictions in the physical world that required more than 10 kW of electricity did.

I won’t belabor this point. I’ve made it before and I wrote about it in more detail in Working Harder and Smarter if you want the full thing, but the point is that if entrepreneurs come up with ways to produce cheap, clean, energy and get it to where it’s needed, people will find a use for it. There is a theory related to this, Jevons Paradox, which says that when technology increases the efficiency with which a resource is used, people actually use more of it, not less, because the lower price induces more demand. Jevons came up with the theory by observing that the increased efficiency of coal use led to more demand for coal. We give people more energy, or more efficient energy, and they find ways to use it.

So that’s reason number one: energy is as close to a bottomless market as there is.

The second is that nuclear startups are producing very different products for very different markets. Nuclear reactors are a technology that enables these companies to serve various needs.

Pitchbook tracks 48 nuclear fission companies, mostly startups