Source: U.S. SEC official website Translation: Shan Ouba, Jinse Finance

On Friday, August 23, local time, Federal Reserve Chairman Powell delivered a speech at the Jackson Hole Annual Meeting. As the global market was looking forward to this moment, the Federal Reserve Chairman publicly announced that the Federal Reserve has officially entered a cycle of interest rate cuts.

The following is the full text of the speech:

Four and a half years after the pandemic began, the most severe economic distortions caused by the pandemic are receding. Inflation has fallen sharply. The labor market is no longer overheated, and conditions are now easier than before the pandemic. Supply constraints have normalized. The balance of risks to our two mandates has also shifted. Our goal is to restore price stability while maintaining a strong labor market and avoiding the sharp rise in unemployment that would have occurred in an earlier deflationary period when inflation expectations were less firmly anchored. We have made great progress toward that goal. While the job is not done, we have made great progress toward it.

Today, I will first talk about the current economic situation and the future direction of monetary policy. Then, I will discuss economic events since the outbreak of the epidemic, exploring why inflation has risen to levels not seen in a generation and why inflation has fallen sharply while unemployment has remained low.

Recent Policy Outlook

Let us first understand the current situation and the near-term policy outlook.

For much of the past three years, inflation has been well above our 2 percent objective, and labor market conditions have been extremely tight. The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) primary focus has been, and rightly so, on reducing inflation. Prior to this episode, most Americans alive today had never experienced the pain of persistently high inflation. Inflation has caused enormous hardship, especially for those who have had the hardest time coping with the rising costs of life’s necessities, such as food, housing, and transportation. High inflation has induced stress and a sense of unfairness that persists to this day.

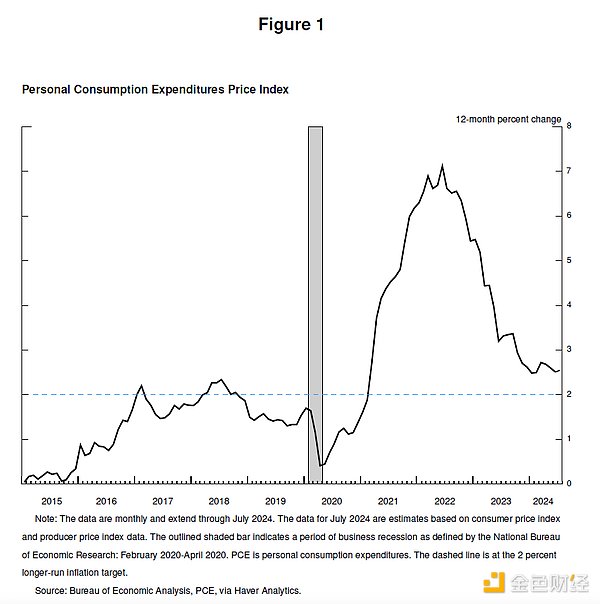

Our tight monetary policy has helped restore balance between aggregate supply and demand, eased inflationary pressures, and ensured that inflation expectations remain anchored. Inflation is now closer to our objective, with prices rising 2.5 percent over the past 12 months. After a pause earlier this year, progress toward our 2 percent objective has resumed. I am increasingly confident that inflation is on a sustainable path back to our 2 percent target.

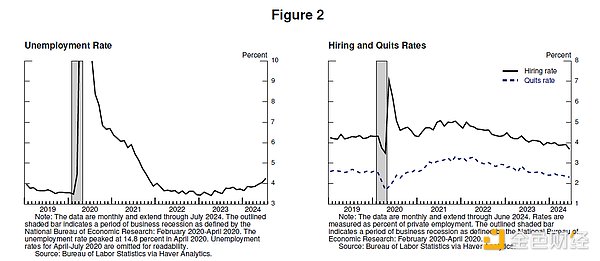

Turning to jobs, in the years before the pandemic, we saw significant benefits to society from strong labor market conditions: low unemployment, high labor force participation, historically low racial employment gaps, and healthy real wage growth, with inflation low and stable, with these gains increasingly concentrated among low-income people.

Today, the labor market has cooled significantly and is no longer as overheated as it was before. The unemployment rate began to rise more than a year ago and is now 4.3%, which, while still historically low, is nearly a percentage point higher than it was at the beginning of 2023. Most of the increase has occurred in the past six months.

So far, the rise in unemployment has not been due to the large layoffs that typically occur during a recession, but rather has primarily reflected a significant increase in the labor supply and a slowdown in the pace of hiring. Even so, a cooling in the labor market is evident. Job growth remains solid but has slowed this year. Job openings have fallen, and the ratio of job openings to unemployment has returned to its pre-pandemic range. Hiring and quit rates are now below their 2018 and 2019 levels. Nominal wage growth has slowed. Overall, the labor market is much looser now than it was in 2019 (before the pandemic)—a year when inflation was below 2%. It seems unlikely that the labor market will become a source of inflationary pressures any time soon. We do not seek or welcome a further cooling in labor market conditions.

Overall, the economy is still growing at a solid pace. But inflation and labor market data suggest that the situation is evolving. Upside risks to inflation have diminished. Downside risks to employment have increased. As we emphasized in our last FOMC statement, we are focused on risks on both sides of the dual mandate.

Now is the time to adjust policy. The way forward is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the changing outlook, and the balance of risks.

We will do everything we can to support a strong labor market while continuing to move toward our price stability goal. With appropriate reductions in policy constraints, there is good reason to believe that the economy will return to a 2 percent inflation rate while maintaining a strong labor market. Our current level of the policy rate provides us with ample room to respond to any risks, including the risk of a further deterioration in labor market conditions.

The ups and downs of inflation

Let us now turn to the question of why inflation rose, and why it fell significantly while unemployment remained low. Research on these questions is growing, and now is a good time to discuss them. Of course, it is too early to make a definitive assessment. This period will be analyzed and discussed for many years to come.

The arrival of the coronavirus pandemic quickly shut down economies around the world. This is a time of uncertainty and significant downside risk. Americans, as always, adapt and innovate in times of crisis. Governments have responded with unprecedented force, particularly in the United States, where Congress unanimously passed the CARES Act. At the Federal Reserve, we have used our powers with unprecedented force to stabilize the financial system and help avoid a depression.

After a historically deep but brief recession, the economy began to recover in mid-2020. As the risk of a severe, prolonged recession recedes and the economy reopens, we risk a repeat of the slow recovery that followed the global financial crisis.

Congress provided substantial additional fiscal support in late 2020 and early 2021. Spending recovered strongly in the first half of 2021. The ongoing pandemic shaped the pattern of recovery. Continued concerns about the pandemic affected consumption of in-person services. But pent-up demand, stimulus policies, changes in work and leisure patterns due to the pandemic, and additional savings from limited consumption of services have combined to drive a historic surge in consumer spending on goods.

The pandemic has also wreaked havoc on supply conditions. Eight million people dropped out of the labor force at the start of the pandemic, and by early 2021 the size of the labor force was still four million smaller than before the pandemic. The size of the labor force does not return to its pre-pandemic trend until mid-2023. Supply chains have been disrupted by the loss of workers, disruptions to international trade links, and dramatic changes in the structure and level of demand. Clearly, this is nothing like the slow recovery that followed the global financial crisis.

Inflation ensued. After running below target in 2020, inflation climbed sharply in March and April 2021. The initial surge in inflation was concentrated in goods in short supply, such as motor vehicles, where price increases were particularly large. My colleagues and I initially judged that these pandemic-related factors would not persist and therefore believed that the sudden increase in inflation would probably pass quickly and would not require monetary policy intervention—in short, that inflation was temporary. The standard view has long been that central banks can ignore temporary increases in inflation as long as inflation expectations remain anchored.

The idea of "temporary inflation" was widely accepted at the time, held by most mainstream analysts and central bank governors of developed economies. The general expectation was that supply conditions would improve quickly, the rapid recovery in demand would come to an end, and demand would shift from goods to services, thereby reducing inflation.

For some time, the data were consistent with the hypothesis of transitory inflation. Monthly readings of core inflation declined each month from April to September 2021, albeit at a slower pace than expected. By mid-year, support for this hypothesis began to weaken, and our communications reflected this. Starting in October, it became clear that the data no longer supported the hypothesis of transitory inflation. Inflation rose and spread from goods to services. It became clear that high inflation was not transitory and that a strong policy response was required if inflation expectations were to remain anchored. We recognized this and began adjusting policy in November. Financial conditions began to tighten. We initiated rate increases in March 2022 after winding down asset purchases.

By early 2022, headline inflation was above 6% and core inflation above 5%. New supply shocks emerged. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to sharp increases in energy and commodity prices. The improvement in supply conditions and the shift in demand from goods to services took longer than expected, in part because of further developments in the United States. The pandemic also continues to disrupt production in major economies around the world.

High inflation rates are a global phenomenon that reflects shared experiences: a rapid increase in demand for goods, tight supply chains, tight labor markets, and sharp increases in commodity prices. Inflation around the world is unlike any period since the 1970s. Back then, high inflation was entrenched—something we were deeply committed to avoiding.

By mid-2022, the labor market is extremely tight, with labor demand increasing by more than 6.5 million since mid-2021. This increase in labor demand is due in part to workers rejoining the labor force as health concerns begin to subside. But labor supply remains constrained, with the labor force participation rate remaining well below pre-pandemic levels by summer 2022. From March 2022 through the end of the year, job openings were almost twice the number of unemployed people, indicating a severe labor shortage. Inflation peaks in June 2022 at 7.1%.

Two years ago from this podium, I discussed some of the pain that fighting inflation might bring, such as higher unemployment and slower economic growth. Some have argued that a recession and prolonged high unemployment are needed to bring inflation under control. I expressed our unwavering commitment to restore full price stability and to keep doing so until the job is done.

The FOMC did not back down, steadfastly fulfilled our mandate, and our actions powerfully demonstrated our commitment to restoring price stability. We raised our policy rate by 425 basis points in 2022 and an additional 100 basis points in 2023. We have maintained our policy rate at its current tight level since July 2023.

Inflation peaked in the summer of 2022. In two years, inflation has fallen 4.5 percentage points from its peak, while unemployment has remained low, a welcome and historically unusual result.

Why has inflation fallen without unemployment rising significantly?

Pandemic-related supply and demand distortions and severe shocks to energy and commodity markets were important drivers of high inflation, and their reversal has been a key part of the decline in inflation. These factors took longer to unwind than expected but ultimately played an important role in the subsequent decline in inflation. Our tight monetary policy has encouraged a modest decline in aggregate demand, which, combined with improvements in aggregate supply, has reduced inflationary pressures while allowing the economy to continue to grow at a healthy pace. As labor demand has slowed, the historically high level of job openings relative to unemployment has normalized, primarily through a decline in job openings without large and disruptive layoffs, making the labor market less of a source of inflationary pressure.

On the critical importance of inflation expectations. The long-standing view of standard economic models is that inflation will return to target as long as product and labor markets are balanced—without an economic slowdown—as long as inflation expectations are anchored around our target. This is what the models say, but the anchor of long-term inflation expectations has never been tested by persistently high inflation since the 2000s. It is far from certain that the inflation anchor will remain anchored. Concerns about a decoupling of inflation expectations have fueled the view that a slowdown in the economy, particularly in the labor market, is required for inflation to fall. The important lesson from recent experience is that anchored inflation expectations, combined with strong central bank action, can achieve lower inflation without requiring an economic slowdown.

This narrative attributes the rise in inflation primarily to the unusual collision between overheated and temporarily distorted demand and constrained supply. While researchers differ in their methods and in their conclusions, a consensus seems to be emerging that I believe attributes the main cause of the rise in inflation to this collision. Overall, the recovery from the distortions of the pandemic, our efforts to moderately restrain aggregate demand, and the anchoring of expectations are working together to put inflation increasingly on a path that will sustainably reach our 2% target.

Achieving lower inflation while maintaining a strong labor market is only possible if inflation expectations are anchored, reflecting the public's confidence that the Bank can achieve 2% inflation over time. This confidence has been built over decades and has been strengthened by our actions.

This is my assessment of events. You may have a different view.

in conclusion

Finally, I want to emphasize that the pandemic economy is proving to be unlike any previous period, and there is much to learn from this extraordinary period. Our Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy underscores our commitment to review our principles every five years through a comprehensive public review and to adjust them as appropriate. As we begin that process later this year, we will remain open to criticism and new ideas while preserving the strength of our framework. The limits of our knowledge—made apparent during the pandemic—require us to remain humble and skeptical, focused on learning lessons from the past, and nimbly applying them to current challenges.