Source: Zhou Ziheng

Every August, central bankers from around the world gather in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, a ski resort in the central United States, for a "symposium" organized by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Bankers use this opportunity to discuss monetary policy and its effectiveness in "managing the economy," especially "controlling" inflation and providing the right amount of "liquidity" to the financial system.

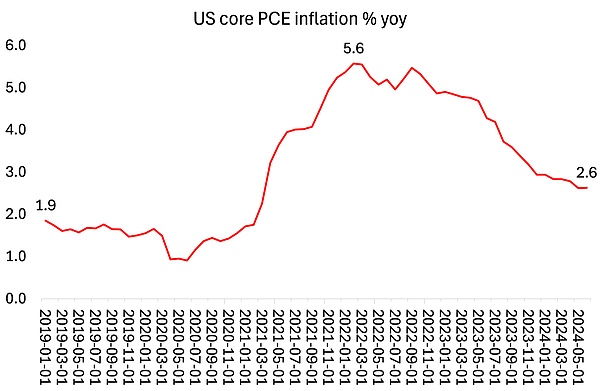

This year’s symposium comes as the Fed faces a dilemma over whether to cut its “policy” interest rate as the economy shows signs of cooling but inflation remains “firmly” falling toward the Fed’s 2% target. The so-called policy rate sets the floor for all borrowing rates for households and businesses in the U.S. (and much of the world). It is currently at its highest level in 23 years.

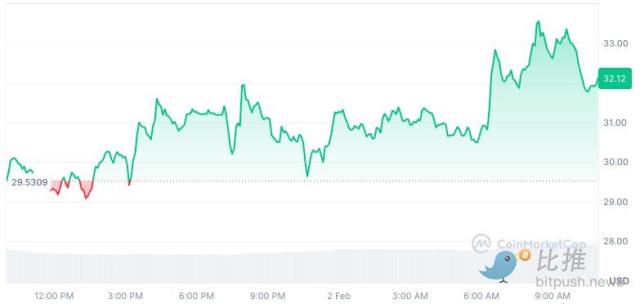

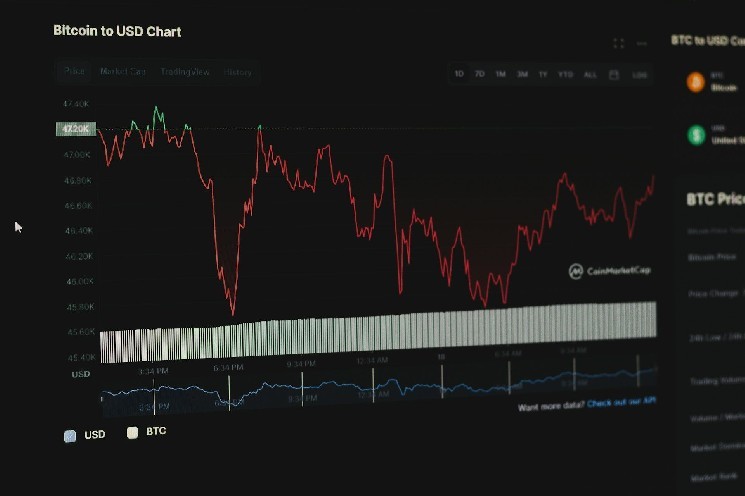

In early August, financial markets panicked and began selling corporate stocks in response to the Fed’s decision not to cut its policy rate at its July meeting, and then July employment data showed a sharp drop in net job growth and a rise in unemployment. However, markets gradually calmed down after the latest inflation data showed a further (modest) decline in inflation, especially as Fed Chairman Jerome Powell began to make it clear that the central bank would cut interest rates at its September meeting.

Powell reiterated that view in a speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium on Friday. " We have resumed progress toward our 2 percent objective. I am increasingly confident that inflation will return to 2 percent on a sustainable basis...The labor market has cooled substantially from its prior overheating. It seems unlikely that the labor market will be a source of elevated inflationary pressures any time soon...A further cooling of labor market conditions is undesirable and unwelcome. Now is the time for a policy adjustment. The way forward is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks."

Powell then claimed that the Fed’s monetary policy had kept the U.S. economy from entering a recession and kept inflation down. “Our restrictive monetary policy has helped to restore balance between aggregate supply and aggregate demand, mitigate inflationary pressures, and ensure that inflation expectations remain anchored.” He argued that prices were rising because of a combination of increased consumer spending and supply shortages. That’s true, but the question is which factor was dominant. Most, if not all, studies of periods of inflation show that supply factors dominated, not excess consumer demand, government spending, or “excessive” wage growth — arguments central bankers used at the time to justify big rate hikes.

But Powell hinted at the real reason in his speech, saying: "High inflation is a global phenomenon that reflects common experiences: rapid growth in demand for goods, tight supply chains, tight labor markets, and sharp increases in commodity prices." This also explains the subsequent decline in inflation: "Supply and demand distortions caused by the epidemic, as well as severe shocks to energy and commodity markets, are important drivers of high inflation, and the reversal of these factors is a key part of the decline in inflation. The dissipation of these factors took much longer than expected, but ultimately played an important role in the subsequent deflation."

Nonetheless, Powell continues to promote the narrative that the central bank’s “restrictive monetary policy” has worked by “moderating aggregate demand .” Powell also reiterates the myth that the central bank’s monetary policy helps “anchor inflation expectations ,” which is allegedly the key to controlling inflation. But this is again nonsense, as recent research clearly shows that “expectations” have little to no impact on inflation. As Fed economist Rudd recently summarized: “Economists and economic policymakers believe that households’ and businesses’ expectations of future inflation are the key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and uncritical adherence to it can prove prone to serious policy mistakes.”

Powell has also proposed other mainstream concepts to explain inflation and to justify their "restrictive monetary policy." The first is the so-called "natural rate of unemployment" (NAIRU). The theory is that there is an unemployment rate that is low enough to maintain economic growth without inflation, but not high enough to indicate a recession. But the NAIRU is another short-lived and fickle feast that cannot be measured.

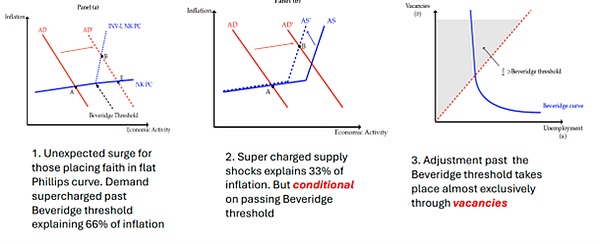

The NAIRU is related to the so-called Phillips Curve, a product of Keynesianism that argues that when the labor market is too "tight" (i.e., unemployment is below the NAIRU), excessive wage increases can lead to inflation. There is a "trade-off" between wages and inflation. This theory was empirically refuted in the 1970s when the economy experienced "stagflation" (i.e., rising unemployment, slow growth, and rising inflation).

Since then, several studies have shown that there is no “curve” at all, and that there is no correlation between movements in unemployment, wages, and inflation. In fact, Powell’s comments on the NAIRU are the exact opposite of what he said at the 2018 Jackson Hole Symposium, when Powell suggested that there might be no use in following the usual traditional “indicators” (i.e., the NAIRU, which measures when the economy is running at its optimal speed) or the natural rate of interest (which measures when borrowing costs are appropriate).

Third, the idea that there is a natural rate of interest that keeps inflation in check without hurting economic expansion, and that central banks should measure and stick to it, is at odds with the realities of capitalist production. Even the hawkish ECB President Isabel Schnabel admits: “ The problem is that it cannot be estimated with any confidence, which means that it is extremely difficult to operationalize… The problem is that we don’t know exactly where it is .” (!)

Clearly, these natural rates of harmonious non-inflationary growth have been moving! "Navigating by the stars sounds simple enough. However, using the stars to guide policy in practice has recently become quite challenging because our best assessment of the position of the stars has shifted significantly. Schnabel continues: "Experience has revealed two realities about the relationship between inflation and unemployment that are directly related to the two questions I began by asking. First, the stars are sometimes far from where we perceive them to be. In particular, we now know that the level of unemployment can sometimes be very misleading about the state of the economy or future inflation relative to our real-time estimates of NAIRU (u*). Second, the reverse is also true: inflation may no longer be the first or best indicator of tight labor markets and rising pressures on resource utilization." As an indicator, then, inflation is pretty useless.

The 2024 Jackson Hole Symposium continued with several well-respected mainstream economists presenting papers on the effectiveness of monetary policy. One of the papers revisited the Phillips and Beveridge curves’ explanations for the surge in U.S. inflation after the 2020 pandemic crash. The Beveridge curve describes that as job openings rise, inflation rises and vice versa. The speaker told the central bankers, “The pre-surge consensus on these two curves needs to be substantially revised.” In other words, the existing mainstream theory cannot explain the recent post-pandemic inflation surge. The speaker attempted to propose a series of revised curves that are now based on job openings instead of unemployment.

Still, Powell declared monetary policy a success: “ All told, the healing of the pandemic distortions, our efforts to control aggregate demand, and the stabilization of expectations have combined to put inflation on a path toward our 2 percent objective that looks increasingly sustainable.” And that’s without the recession that was feared and spooked financial markets just three weeks ago. A “soft landing” for the economy is still on the cards, with the “Goldilocks” scenario of strong economic growth, low unemployment, and low inflation on the horizon.

I pointed out in my previous article that the market crash three weeks ago does not yet foreshadow a recession. For me, the key indicator is first and foremost corporate profits. So far, profits in major economies have not fallen into negative territory.

Source: Refinitiv, corporate profits in five largest economies weighted by GDP, my calculations

But the U.S. economy and other major economies are far from out of the woods. Price inflation remains “firm,” meaning it looks like it will run at least about 1% above the central bank’s target.

This is also what the ECB presidents attending the seminar are worried about. Bank of England Governor Bailey said: "The question we still face is whether this persistent factor will decline to a level consistent with inflation reaching the target on a sustained basis, and what needs to be done to achieve this goal. Is the persistent decline basically set in as the overall inflation shock fades, or does it also require a negative output gap, or are we experiencing a more lasting change in the setting of prices, wages and profit rates, which will require monetary policy to remain tight for a longer period of time?" ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane also doubted whether monetary policy can play a role in the "last mile" of "fighting inflation".

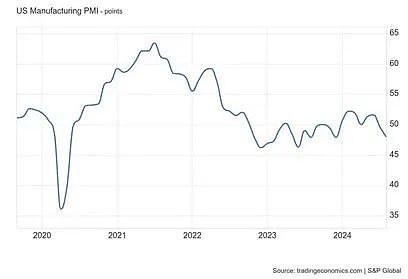

Meanwhile, among the major economies, real GDP growth (and especially real per capita output growth) was very weak. Only the United States saw a notable expansion, and even there, sales growth did not exceed 1% if exports and inventories were stripped out. The rest of the G7 economies were either stagnant (France, Italy, the United Kingdom) or in recession (Japan, Germany, Canada). The situation in the other advanced capitalist economies (Australia, the Netherlands, Sweden, New Zealand) was not much better. The manufacturing sector was in deep contraction in almost all the major economies.

Moreover, there will soon be a new American president who will either want to raise import tariffs to record levels, thereby stifling world trade and raising import prices, or impose new taxes on corporate profits - neither of which is good news for American capital.

Jackson Hole celebrated success, but what it really revealed was that central bank monetary policy has played little role in bringing inflation down from its peak in 2022; it has played little role in achieving output or investment growth; and it has little ability to prevent rising unemployment or future production declines. All high interest rates have done is to push many small businesses into bankruptcy or more debt; and to drive mortgage rates and housing rents to their peaks. Cutting rates now would only stimulate the stock market, not the economy.