Introduction and purpose

Hi, my name is Nathan Gunawan and I’m a co-founder and CEO in Pallav Technologies.

Usually my personal business introduction stops there. Maybe it touches upon my educational or work history in slight detail. But only for 20-30 more seconds.

Recently, I’ve noticed the older, more senior folks slow down the pace: more curious about personal background: my family, where I grew up, my hobbies, my personal “end game”. It got me to thinking: it’s rare for me to be asked these questions by most, but maybe these are the questions that truly matter.

From an investor or long-term business partner perspective, it’s a bit odd, isn’t it? You trust significant sources of capital —financial, social, professional — without knowing who the other side really is. But evidence showcases that understanding the personal deeply is fundamentally what matters.

The best understand this. For instance, they understand that most startups pivot and transition to different territory than they originally started with, and it’s the founder’s resilience and curiosity that enables them to push through to better ground.

It’s why Hummingbird looks for a special kind of founder (“unique childhood trauma”). It’s why people like Harry Stebbings from 20VC constantly emphasize the “who” nature of early stage investing.

As a founder myself, it got me thinking. I might not have much face time to share my deep personal story. Neither is it always comfortable for the investor to request vulnerability during real-time due-diligence. So instead of putting it under the table, why don’t I just share my story out in the open? Instead of just surface level facts, I could write in more detail of things below the surface: the tapestry, good or bad of my life.

The best investors and business partners will check everything they can get their hands on. I was told that my Substack writings (e.g. on fintech) have been helpful in giving investors confidence in my knowledge of financial services.

In the best case, maybe this story draws in people who resonate with the values that I’ve built throughout life so far. And there’s no worst case — it’s just the facts of my life! So let’s dig in.

Early childhood & moving to Singapore

I was born in Jakarta on September 4, 1997. From what I remember, it was a standard childhood thankfully devoid of much pains or troubles. My mom Maria was a stay at home mom, and my dad Charles was a finance professional working as an investment banker in Indonesia out of a local bank.

There were two major catalysts in my childhood that shook up what was at that point “ordinary life”.

The first catalyst was the birth of my sister, Nicole, in 2003 when I was 6 years old. Unfortunately, Nicole was born with a rare condition called chronic vomiting syndrome that was detrimental to her day to day life. At that time, the condition was still not well understood, and thus hard to treat. The implication was that she would get “attacks” on a frequent basis, during which she would constantly vomit sometimes up to 20-30+ times per day. During these attacks, she would have to go to the hospital to get connected to an IV drip. Many things would trigger attacks, but one of the potential causes was bad air (to which we all know pollution in Jakarta to be the case).

The second catalyst was the acceleration of my dad’s career. When I was 8 years old, he was recruited as a Managing Director to lead Goldman Sachs’ Indonesia strategy. From 2005, he was formally employed and positioned more in Singapore (although most of his origination work was still in Indonesia).

These two catalysts met each other and in 2006 when I was 9 years old, my family decided to use the opportunity while my dad was under an employment pass to relocate to Singapore. Medical care and atmosphere would be better for my sister. From the outset, it seemed like things would get better.

I quickly adjusted to Singapore. My dad placed me to study in Singapore American School (to my mom’s initial chagrin, who wanted me to go to a local Singaporean school). My dad’s rationale was clear: Americans were more well-rounded and extroverted, and intellect alone did not result in success. I was then a shy, introverted child. And thus, I would be more challenged to grow in an American school environment. Though I would go on to fracture my arm in the first few weeks of school, I adapted pretty well to the American environment. I read a lot more books (sparking a lifelong habit), played more sports, and became much more social and imaginative.

At the same time, my sister slowly got better. Our family found treatments that started to work and the intensity of her condition began to recede: slowly, but surely.

While this was going on, my father’s career continued to progress and he ended up taking on a Country Head role at Credit Suisse Indonesia in 2008. When I was 11, my Dad was back to predominantly being in Indonesia while my family decided for my mom, my sister, and myself to stay back in Singapore. This decision would begin the catalyst for the next stage of my life.

Parents’ divorce & depression

Due to my Dad’s work and the broader family’s decision to stay back in Singapore, my Dad would end up taking on a schedule that only now I can truly appreciate. He would stay in Indonesia during the weekdays and on Fridays would fly back to Singapore to spend time on the weekends with the family.

“Imagine being low on sleep and all you want to do is sleep, and pushing yourself to take a cab on a 2-3 hour traffic one-way ride to the airport to go to Singapore every week. It was tough even if I wanted to be with the family.” — I can definitely imagine how exhausted my Dad was, especially with the increased responsibility that his work demands placed.

At the same time, my Mom was giving her all to raise us. Not only did she dedicate herself to my sister’s condition, but also made sure that we were taken care of to the best of her abilities (that I can appreciate only now). She drove us around Singapore to Math and Chinese after-school tuitions. She drove to Yishun twice a week to send me to golf lessons. Not only that, but she also took up a job as a real-estate agent, making herself known to Indonesian families who were looking to buy properties in Singapore which then was a highly liquid, lucrative market.

However strong both individuals were though, my Mom and Dad’s relationship slowly started to break. Maybe it was due to incompatibility. Maybe it was the distance. But as a child, though young, I could observe the relationship slowly but consistently withering away. Week after week.

Fights happened more often around the household. Each one grew more and more intense as months passed by. Fights started to happen not only between my Mom and my Dad, but the anger seeped to affect the family as a whole. I remember when I was in middle school, asking my church mentors: “Will my Dad and Mom divorce?” It seemed like a constant possibility that things would come crashing down in any second. I could sense and see that both my Mom & Dad were deeply unhappy.

As a result of home life being hostile, I retreated into my own world. This was about the ages of 11-14. It was tough to be honest to not be able to share this to anyone else (especially at that age). I escaped into video games, and my confidence was low. On top of all this, I had a severe case of cystic acne, which seems like it would be such a trivial thing, but it actually exacerbated and made my confidence continue to spiral down, especially in middle school when kids were at their meanest and I was at my most self-conscious.

I was also not particularly naturally gifted in anything, at least that I knew at that time. I might have been above average at academics, but I was not #1. I wasn’t particularly the best at sports, music, pretty much anything. This was also a confidence hit.

I remember being severely depressed at this point in my life between 11-14.

All of this culminated in my parents divorcing when I was 18 years old. To be honest, it was an extremely messy situation. Both sides are not on good terms and the fall-out of the divorce was tough to deal with. However, if there was a great thing to come out of the circumstance: it’s that it forged my ability to handle pain for long periods of time, and forced me to be independent and find my own path.

I am fortunate to come out of this with much better individual relationships with both my Mom and my Dad. It has taken a lot of work (including a personal decision to come back to Indonesia to resolve this which I’ll touch upon later) and humbling myself down to get to this point where I can say I am no longer resentful. As a founder of a financial services company, I enjoy the bonding and mentorship I am now able to have with my Dad (over glasses of wine). I also enjoy a better relationship and immense gratitude for my Mom, who has sacrificed and given a lot of herself to raise both me and my sister.

High school: The birth of my my “fire” & distance running

I somehow was able to dig out of this hole at about 14 years old. It’s unclear to me why, but there was seemingly a mental switch that occurred. All I remember is sitting in Math class on my first day of high school and thinking to myself: “We need to be very serious now.” From then on, I remember excelling in academics at the top-level in all subjects (despite previously only being above average, not anything remarkable). I had a fire to be at the top.

Meanwhile, on a friend Shiv’s suggestion, I decided to try out for the Cross Country (long-distance running) team in 10th grade (when I was 15) despite not having any previous athletic background, much less in a competitive way. Shiv suggested that I train over the summer to prepare for try-outs the following August when school started again. In order to make the JV team, I had to run a mile under 6 minutes and 30 seconds.

So that summer after 9th grade, I ran everyday. My fitness levels were complete garbage in the beginning, but I increased the distance and speeds such that I was running 10Ks comfortably by the end of the summer. I returned to school for 10th grade and the try-outs are still vivid in my memory: I was going to do the mile time-trial while the existing Cross Country team was doing mile repeats. Somehow, fighting for my life, I crossed the line in 6 minutes and 27 seconds. I literally teared up. This was the first time I felt true pride. I worked so hard to achieve something. This was the first team and real accomplishment that I had ever made.

I started as the slowest runner on the team, but resolved to myself that I would make it to Varsity and eventually become one of the fastest people on the team. I remember during a training when a Varsity teammate Michael was sharing a story of how he started running two years back, put in more hard work than anybody else (even those who had ran for years beforehand), and now was the #3 fastest runner on the team. I took that story to heart without anyone knowing. I was going to work harder than anyone else to succeed.

And so I did. I trained extremely hard. During the season, I never missed any optional weekend runs. After the season, I ran every single day with some members of the Varsity team with an external coach named Twiggs. This mentality carried itself over for all of the high school years, to the point where in the Summer prior to 12th grade I was running 100+ miles a week, running twice a day, trained by a coach named Rameshon.

I was obsessed with hard work. “Hard work beats talent when talent does not work hard”. “Champions are made in the off-season”. These were sayings that I carried on my sleeve.

And hard work did pay off. When I was in 12th grade, I was the #2 fastest runner on the team, and had made it to the IASAS team, selected runners that would represent our school in international competitions (one of 7). My mile time had dropped by 2 minutes since the time I had tried out for the first time. But more than just the outcome, I developed a sense of confidence and assuredness in myself and my abilities. I knew that in anything I did, I could put in the work despite coming from behind. I also developed the knowledge that hard work patiently applied over long periods of time would yield results. You could not hack, or take shortcuts to success. This carried over and continues to carry over to everything that I do.

Remarkably though, being an athlete was not the most memorable part of this phase of my life. I found myself drawn to the act of creation and creating impact beyond myself.

Prior to my own training sessions, I volunteered to be an assistant coach to Middle School runners. I saw an opportunity to nurture a deep passion for the sport and a work ethic that transcended into their character, and so I would train with them on weekends as supplementary training both in-season and off-season. Similarly, with my belief in hard work, I built an off-season training group for High School runners called the Eagles Distance Project whose goal was to sharpen individuals to make it to Varsity. I would coach, motivate, and create training programs all-year long. Many of the runners I trained since Middle School went on to be top runners in High School, some of whom even went on to set inter-school records and compete in college.

Building Eagles Distance Project made me realize that I could have a part in building something that had a significant impact on others' lives. I could utilize the knowledge and abilities I had gained to positively impact others. In many ways, this was the spark of the entrepreneurial soul that I have since developed.

I executed in High School to a strong degree. Academic and extracurricular excellence opened doors, and I chose to go to Northwestern University to pursue my undergraduate degree in Mathematics.

College at Northwestern: Exploration & Perspective

College was a natural evolution to the lessons that I learned in High School, particularly in the areas of creation, entrepreneurship, tackling unknowns, gaining perspective, leadership, and grit.

Interestingly enough, the first 2 years of college were more dedicated to trying new things out. College was the first time I had intellectual and personal freedom in such a different way than the structured nature of High School. I joined an a cappella group (X Factors), joined two true American white-guy fraternities (Delta Chi, Beta Theta Pi), became the Co-President of a Greek service club GreekBuild, was even elected as one of the VP’s of the Interfraternity Council that governs the fraternities at Northwestern, and crazily was even one of two guys as part of Northwestern’s Varsity Cheerleading team throwing girls up in the air. While none of these things ever impacted me in a continuing, significant personal capacity — it did push me beyond my boundaries to meet people I would have previously never interacted with, and secondly teach me that I was great at sales. I went from an traditional Asian guy raised in Singapore who did not know anything about football, to getting the #1 bid at a fraternity (which apparently is a big deal) and being elected to multiple leadership positions to govern the frat system. What a crazy story.

On the other side of this, funnily, I also developed a passion for the education space after time doing extracurricular teaching at a public school in Chicago. It opened my eyes to the reality of life outside of my socioeconomically homogenous and upper-middle class bubble. I was teaching predominantly immigrant Hispanic, Asian & Black kids who were from low-income backgrounds. I noticed many students did not have the confidence that I took for granted — that going to and paying for college, working hard to get a good job was a no-brainer. Many did not have the examples and confidence to be able to strive for something bigger.

And so, despite being destined to a traditional finance track with my Dad’s background and an initial freshman year internship at Northstar Group’s private equity team, I actually decided in my sophomore year to do an internship with Teach for America under their Accelerate Fellowship (one of the leading education non-profits in America). It brought together extremely smart kids from schools like Yale, Dartmouth, Penn with backgrounds that were vastly different from my own — and took us to different parts of the country: from Los Angeles, to New Orleans, to the Rio Grande Valley in Texas — to support and to understand different educational stakeholders and their unique needs across a variety of functions from non-profits, school boards, and school leadership.

If there’s one thing I know for sure, unlike other people who may have stuck to a homogenous group all throughout college (e.g. Indonesians hanging out with only Indonesians). I totally pushed myself to the limits to meet people vastly different from me, and to understand and empathize with situations that I had never experienced. This was a truly transformational time.

And then in my junior year of college, I pretty much quit the entire frat system realizing it was mostly a waste of time and started focusing much more on getting forward in life. I became much more serious about my studies in Mathematics and Applied Science after a transformative class called Analytics for Social Good where I realized analytical problem solving could truly result in insights that shape progress. I built product management and customer support knowledge through a summer internship with a now-IPO tech company ServiceTitan. And I took in my own time a bootcamp with General Assembly where I built data science and machine learning skillsets.

And my passion for creation continued to blossom. After my years of long-distance running, I decided I was too skinny for girls and decided to build muscle doing power-lifting. That same competitive fire I had as a runner led me to pursue powerlifting in a competitive manner, and resulted in me building Northwestern’s Powerlifting Team. I took the sport and the team seriously, and we went to Nationals twice. I brought a group of individuals together to appreciate and be able to bond and grow together over the sport (which used to be such an individual thing). Again, it was a realization that one could create a significant life impact for others through the act of creation.

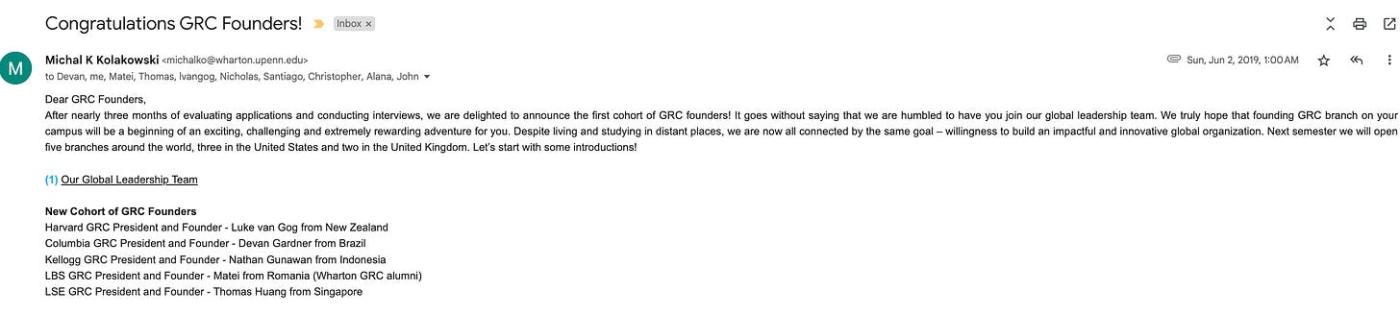

And in my senior year, I upped the stakes once more for the act of creation (which at this point was relegated to the area of sports). Through a chance connection to a girl at Penn named Candice, I was connected to the Penn Facebook feeds and chanced across a successful social impact consulting club called GRC (Global Research and Consulting Group) that was looking to expand outside of Penn to other universities, and was looking for potential founders of school branches to apply.

Having been part of an existing consulting club and realizing that the skills consultants learn are tremendously valuable in any career (namely structured problem solving), but that most consulting clubs are tremendously “pre-professional” and too focused on people that are purely gung-ho about getting a consulting job — I saw GRC as an opportunity to flip the script and create a sort of “anti-consulting consulting club”. I pitched this idea to some strangers who came highly recommended after an initial LinkedIn post I made (Vishal, Kinnera, Sharad, Rushmin), and somehow we got a legendary team together. I reached out to a few CEOs running impact related companies and we ended up securing our first client, an EdTech company Innovare (which has since raised $5 million) for a transformation project where we helped them identify gaps in their sales enablement, specifically the de-motivation and lack of guidance for newly joined sales members.

We expanded GRC quickly after our first engagement, and got more than 20 new people to join the club and 3 new clients in the second quarter including big names like Education for Employment and Arc Thrift Stores. We passed on the leadership and GRC continues to grow as one of Northwestern’s leading and most popular clubs.

Building GRC was a bit different than the previous acts of creations which were mostly individual acts. GRC was the first time I built together with a group of co-founders who shared deep ownership and enabled capabilities (e.g. scaled campus recruiting) that I could have never done alone. Beyond learning how to build together with a team, it made me realize the power of mission to empower people to unify to tackle a common problem. These skills would be the building blocks that powered my future entrepreneurial efforts.

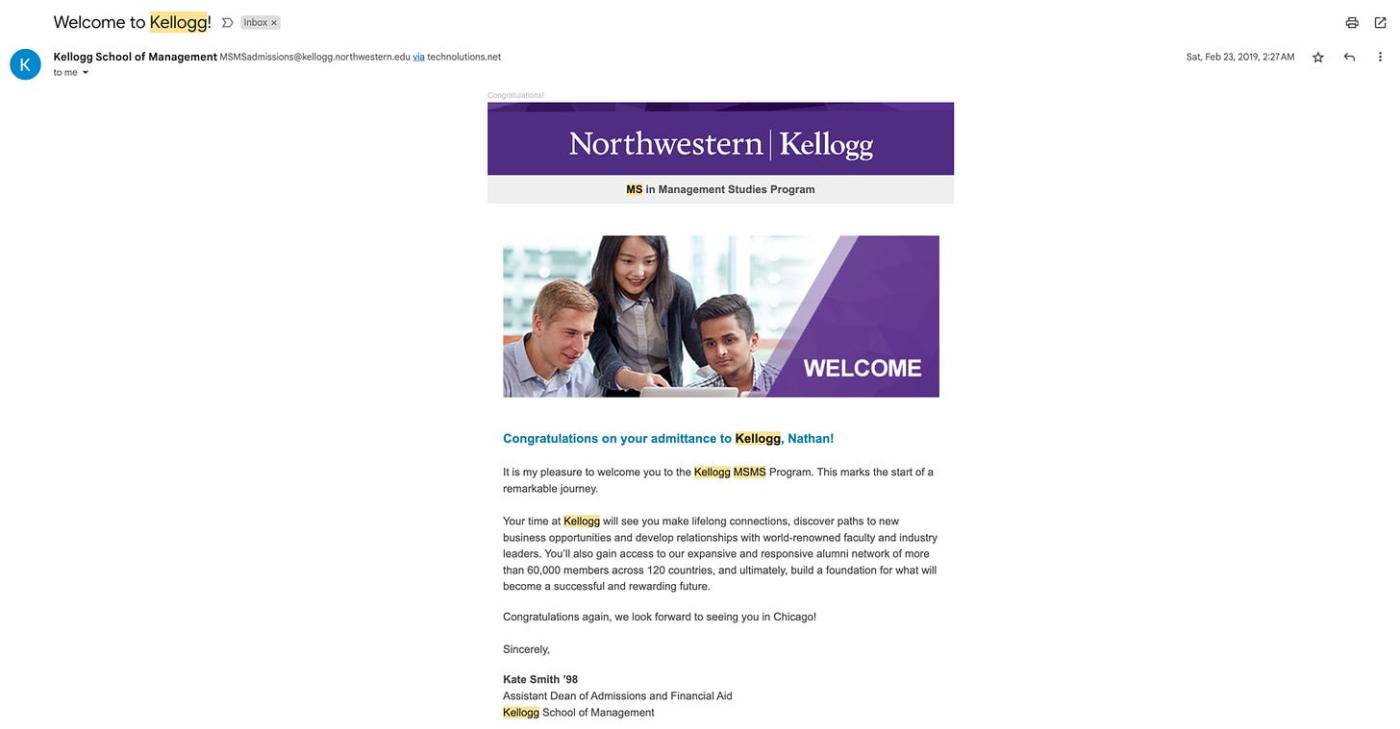

Kellogg & Cornerstone Education

When I was in my senior year of college, I decided to apply for the Kellogg Master’s in Management Studies program (MSMS). It was a selective, one year post-undergraduate master’s program only for Northwestern undergraduates that promised to be similar to the first year of an MBA program, building the foundations of a business education: from accounting, finance, strategy, economics, operations, marketing, so on and so forth. It was the perfect program to complement a STEM education, where I mostly built technical skills. This was the ideal next step. If I did not get in, then I would consider alternatives.

I applied, and got wait-listed in November 2018. Damn, that hurt. I was told that they would get back to me in February of the following year. I was extremely determined to show that I was competent and committed to succeed in the program. I constantly followed up, sent in an updated transcript that semester (where I achieved all A’s in tough math classes), an expanded statement of commitment where I reaffirmed how I would add value to and receive value from the program from a uniquely analytical background, and pestered a few Kellogg folks I knew to give me a recommendation to the folks at the Admission’s office. In February, the Admissions Director called me and I was formally accepted into Kellogg. It was the perfect example of the grit I developed throughout my time as a runner, utilized to overcome a setback.

Funnily enough, though I was initially waitlisted, I ended up excelling at Kellogg and graduated as the Valedictorian with top academics, and the only one in my class to be guaranteed acceptance to the 1-Year MBA program in 2-5 years post-graduation. Personally, I gained a tremendous amount from the Kellogg education and ensured that I made the most out of the experience.

One particular course changed my life, and that was “Entrepreneurial Selling” by Andrew Sykes. Being able to witness and put in practice how world-class sales leaders executed, convinced, and negotiated made me so tremendously prepared to act in the CEO role I am in today, and pushed me to be able to understand that great selling takes a lot of knowledge, vulnerability, and guts. It’s not fluffy bull-shitting.

As I was taking “Entrepreneurial Selling”, I was inspired to build a venture that would end up being my first “non-college/high school creation”, and one of the catalysts that drew me back to Indonesia. This was Cornerstone Education. I had learnt over a short summer vacation back home that many Indonesians who attended expensive international schools relied upon “college counselors” who charged upwards of $20,000+ to help students excel in their college admissions journeys: from essay writing services, to even helping the student choose their extracurriculars or make up a fancy entrepreneurial story that was untrue (where the kids’ parents would then pay a local news outlet to cover this). It baffled me, and struck me as complete grift. After sitting on it for a few weeks and researching more, I had also realized that international students were completely eligible for significant scholarships in US universities. The idea struck me: what if I could build the same caliber of college application guidance but direct it towards smarter, but less privileged students in Indonesia, and for 100% free. I knew there must be a ton of “hidden talents” and I was determined to build a service to make “doing the impossible” a reality. What if a local student from Indonesia who had zero access to these services managed to find a pathway into Harvard? It was my mission to find a way to be able to prove this hypothesis.

But the first problem to tackle: I knew basically zero Indonesians (given Northwestern was devoid of Indonesians and I had never really grown up in the country myself having moved to Singapore young). And I needed to know Indonesians to make this a reality: as I needed to hire mentors to teach students, and to be able to scale our message so we could find our students. So again, I hustled. Somehow and potentially serendipitously at about the same time, I was connected to a girl studying in Wharton named Annissa from a friend Rom who used to be in the same high-school inter-league association, and whom I used to sing with. At this point I had already decided to go to Indonesia to work at Bain, and Annissa similarly had decided to go to McKinsey in Indonesia. Rom had thought it would be a good connection given our backgrounds, but initial conversations with Annissa revealed a shared passion for social impact and educational equity. So I hustled to try to convince her to be my co-founder for Cornerstone, flying out during Spring Break to Pennsylvania to try to seal the deal in person. Fortunately she said yes, and Annissa broadened our network to convince other great individuals to join our team (like Tasha, Gaby, Moses, Sam).

In parallel, I was also cold-messaging a bunch of Indonesians from all of the top colleges I could find on LinkedIn. I got on calls with anyone who would even respond to me. These included people like Michael, Kenzie, Joanna, Zaki who led our operations, and people that would join as mentors. Slowly but surely over a couple months we had built a solid team of 30+ people.

And by the way, we did this all during COVID. For months, we would meet everyday to build curriculum, plan our recruitment strategy for mentors & mentees, build our growth, branding and marketing, and mentor training. We internalized our mission and propelled ourselves forward. And when we finally were ready to market our mentorship program, we found that we were right: there were incredible Indonesian students who were not your standard rich kid, but who went to local schools and did not realize that studying abroad for undergrad was a potential pathway accessible to them. Cumulatively, our programs ended up helping students get accepted with scholarships to schools like MIT, Duke, Michigan, Notre Dame, Olin, and others.

However, and this became another important insight for me I’ll touch upon later, is that there were cases in which even significant scholarships would not be enough to enable a local Indonesian student from studying abroad. A local Indonesian student named Jasmine got a $60,000 per year scholarship from Olin College, one of the top engineering liberal arts schools. There was a remainder of about $10,000 for room and board, books, that the school could not cover. Her family could not get any long-term loans, it was impossible to convince high-net worth individuals in my network at the time to sponsor her, and thus Jasmine could not go. I was even considering putting my own money to help her (which would be everything at the time, as I was just starting to work), but my family pushed me against it as I was still building up my own savings. But I thought at the time: what a shame. Here was an incredible, diligent girl aiming to study Civil Engineering who would easily pay the delta off in a couple years post graduation at one of the best schools for her field. The fact that financial access was a blocker for her trajectory was deeply saddening to me. I thought to myself that I would return to solve the problem of financial access sometime in my future. Fortunately Jasmine is well, and thriving at one of Indonesia’s top universities now.

We expanded Cornerstone from 2020-2022 beyond just study abroad mentorship, into post-college career preparation as well for local college students in Indonesia who generally lacked the career mentorship that international graduates took for granted. Our motto was to “Turn Underdogs into Winners”. We designed and ran what we called the “Dream Job Bootcamp” (DJBC) which covered 4 weeks of fundamental career search steps, and paired college graduates with young industry mentors who sought to help out. We helped 500+ students, and succeeded in placing many of our mentees to great jobs, some of whom were the first ones in their university to get into workplaces like Bain & BCG. One of our mentees turned team members Beatrice became an Associate in BCG as the first ever student coming from Universitas Ciputra Indonesia.

Personally, running Cornerstone was an extension of my personal drive for impact. Our bootcamps would run every Saturday, while I was working at Bain. Imagine finishing up a crazy week running private equity commercial due-diligences and waking up on Saturday morning to run a session. However, it was so worth it.

I winded Cornerstone down in late 2022 as I needed to prioritize spending more time in my own professional career, and in parallel the stay-at-home effects of COVID were starting to wind down, causing more and more folks to be busy and prefer in-person gatherings and events. While it does not continue today, the lesson was clear: I had the capability and skillset to bring a diverse team of strangers together unified towards a common mission, to build at scale to a non-homogenous audience, to create impact in at that point the biggest way I had done yet, and to also make a lot of friends along the way. Along the way, I went from a person who barely knew Indonesia and Indonesians, to having a wide community of friends and feeling deeply connected to the country — setting the foundation for how I would build my career in Indonesia.

Deciding to move to Indonesia & journey in Indonesia (COVID, Bain, Ministry of Education)

Prior to building Cornerstone mid-way through my journey at Kellogg, I had already made the decision to move to Indonesia post-graduation to work at Bain. It’s important to note that moving to Indonesia would not be “moving back” per se, as I had never spent any formative part of my life in Indonesia. Besides my family, considering I had no existing networks, no existing nostalgia, in Indonesia -- it was not entirely the most apparent decision for me to move to Indonesia, especially given I had job offers already from the US post-graduation that were on the surface “better”.

The first, most fundamental rationale for moving back was family. After a tumultuous childhood filled with resentment, anger, and unrest — I felt that my relationship with my family was not in an ideal place. If I had stayed in the US immediately after graduation, I had a feeling that I would end up staying there forever. Would I regret not at least trying to rebuild my relationship with my family? I asked myself this question over and over again. Eventually, after a lot of reflection, I decided that it was the case. Fortunately it may have been God’s hand: my grandmother got sick with stomach cancer in 2022, and I was the only grandchild in Indonesia at the time until she passed away. At the very least, being able to show my love and presence was something that I cherished.

The second rationale of moving back was driven by speaking to Ernest, a BCG Managing Director and now a good friend. In a coffee chat, he shared that he had found projects in consulting to be much wider in breadth and impact in Southeast Asia compared to the United States. This was because the territory for strategic expansion and development were wider. To paraphrase: Indonesian companies were more inefficient, and hence the room for impact was larger. Comparatively, projects in the US centered more often towards optimizing existing businesses lines to be marginally better. If I wanted to make a larger impact, going to Indonesia would make more sense. And according to Ernest, working in consulting was a great pathway to establish the foundations of a long-term, impactful career. Brand names deeply matter in the region, and working in consulting would build credibility and establish a foundation of important analytical skillsets.

With those two factors combined, I decided to take the role at Bain Indonesia. It came with a lot of nervousness and angst, but I knew I had to just dive into the ocean. Fortunately, I thought at the time, Bain was known as a highly collegial workspace: lots of parties, booze, and known as a continued “college frat”. I would ease myself into Indonesia in a much easier way, so I thought. Little did I know that two months later, COVID-19 would strike and things would completely change. Ironically, I ended up spending a significant portion of my Bain career online, with no in-person components at all in Indonesia.

So I returned to Indonesia in 2020, in the midst of COVID, with zero knowledge of Indonesia, an online career to look forward to and zero certainty of what would happen next. My mom and sister were still in Singapore as my sister was wrapping up her final year of High School. Very fortunately, I was building Cornerstone and was occupied, and gratefully due to Cornerstone had already built quite a sizable group of Indonesian friends prior to even coming back to Indonesia.

My work at Bain started as I was strapped up in a Jakarta apartment in the middle of lock-downs, and I was staffed immediately in the Private Equity Group for a rotational “ring-fence”, where our clients were private equity funds looking at Bain to serve as a partner to diligence the fund’s target from a commercial perspective: analyzing everything from market, competitive landscape, unit economics, and value-creation opportunities. My first case was the diligence of an Indonesian last-mile logistics leader, and I barely left the desk. Realizing that COVID lockdowns were unlikely to end anytime soon, and missing my family (not having even seen my mom & sister since I returned to Indonesia since they were in Singapore), I requested that Bain transfer me to Singapore.

Fortunately, they accepted. I was able to finally see my family in 2021. The Private Equity Group (PEG) was predominantly staffed in Singapore, so I was able to work in the office at a time when the majority of the firm was remote. It was a privilege, as the learning and feedback cycles were so much more active. PEG was extremely fun in the heyday of the COVID tech bubble: I was conducting diligence of the region’s biggest deals with some of the world’s biggest funds as clients, from the private placement of a company that would be then the biggest Indonesian tech IPO, a Series D of a major AI chip maker, the acquisition of an engineering conglomerate. It was a bootcamp in every sense of the word to business fundamentals, and being able to execute in a fast-paced setting. When I left PEG to do general Strategy cases, the skillset shined and I was able to get a top-rated review from my case leader for problem solving. One of my supervisors Meng Yang mentioned I was thinking better than people 4-5 years older in tenure than me, but I was also way messier (appreciate and noted that being organized is definitely not my core competency).

It was also while working at Bain in parallel that I was starting to develop a stronger, more opinionated worldview: shaped by books I read like “Antifragile” and “Skin in the Game” by Nassim Taleb, “From Third World to First” by Lee Kwan Yew, “The Everything Store” about Jeff Bezos and Amazon, and writings by Naval Ravikant. In particular, the principle of calculated risk-taking and willingness to have your “soul in the game” were elements I felt were missing at a stable job like Bain, where a lot of people were worried more about an incremental change in their ratings vs. creating a radical shift in the world. I saw many clearly unhappy people who mentioned they wanted to leave but could not find better paying jobs outside of Bain. I also saw a lot of people who left Bain more confused than ever about what they wanted to do in life, despite people coming in believing the “generalist” experience to be a good way to search for those answers. It made me wonder whether this could really be the end-game for me.

Secondly, given my technical nature, I realized there were harder problems in the technology space that the Bain toolkit would never give oneself exposure to, despite the fact that these would be driven by business entrepreneurs at top tech companies. Imagine a scene from “Super Pumped”: You’re in the War Room at Uber in the early days designing the initial driver supply and rider demand algorithms: you’re making on-the-fly decisions on pricing, designing multivariate experiments across regions, triggering the atomic network to induce substantial network effects. Reading essays from technology leaders like Andrew Chen, Dan Hockenmaier, and from places like NF/X exposed me to how the top of the industry thought. Bain’s toolkit would not enable me to be best in class in driving these highly strategic product decisions in technology companies that have massive implications. I realized that I had skill-sets (e.g. machine learning, product) that were not even tapped into in my time at Bain, which I viewed as a waste if this was all I was going to be doing my entire life.

I realized there was so much more to learn, and I had enough of the toolkit mastered, with the rest able to be learned through experience in the area, or through enough curiosity (e.g. through reading: for instance books like “The Seven Powers”, “Cold Start Problem”, “Platform Revolution” gave me more insight into entrepreneurial business strategy that I never solidified at Bain).

And so when the opportunity came up to search for new roles (of which in 2021 in the tech heyday there were plenty of inbound recruitment happening in my messages), I was open to thinking about what was out there. I considered roles in tech (Shopee, Grab, Xendit) and venture capital / private equity (AC Ventures, INA), but none really hit the spot. I wanted to be exposed to a challenging, long-term mission and be at the forefront of building advanced, technology products.

Then came along a different opportunity: to help Nadiem Makarim, the founder of Gojek who was elected to be the Minister of Education, to build up the technology arm of the Ministry of Education of Indonesia. This was popularly known as his “shadow organization”. The thesis was interesting: instead of deploying technology and platforms to only the private sector, the public sector could also stand to benefit. The GovTech model had worked successfully in Singapore to drive innovation, so it only made sense that it could be ported over to Indonesia. Namely, Nadiem aimed to build the first working proof of concept in the education space. Different products were envisioned and some had already been launched: a procurement / e-commerce platform for schools, a learning platform for teachers and principals to share educational best practices across subjects and grade levels, a centralized data dashboard to monitor school performance and progress, a career platform connecting college students to internships and job opportunities. The thesis so it goes, is that there are some things that the public sector is uniquely positioned to solve — immediate, scaled national change. So it must be that technology could be used for good to drive this transformation.

I was hooked. Nadiem’s journey as founder of Gojek (a household technology name even known in the US as a pioneering super-app) then elected as a Minister of Education was an inspiring story that was one of the other catalysts that made me realize how fast-paced and transformative Indonesia could be, and thus push me to think about going to Indonesia post-college. Where else in the world would the founder of one of the top tech companies become a minister?

Secondly, as someone who had dedicated a massive part of my life to further educational opportunities for others through my time at Teach for America and Cornerstone, furthering educational access was at the forefront of what mattered to me and what I wanted to dedicate my life to build.

Joining the Ministry of Education then became one of my top choices.

The only problem was: I did not know how to speak Indonesian. I grew up pretty much all my life in Singapore, and thus my knowledge of the language was relegated to ultra-basic household words. Bain did not at all immerse me in Indonesian language nor culture, given most of my clients were global funds. But as one can imagine, work in the Ministry of Education would mostly be conducted in Indonesian. This was one of the biggest things that discouraged me from immediately taking the role. I spoke about this fear to a friend Gwyneth. She told me that it was inevitable that I would have to learn Indonesian anyways and be surrounded by mostly local Indonesian folks. What better way to learn the language than to immerse myself fully in an all-Indonesian environment? With that encouragement and coincidentally also reading “Skin in the Game” by Nassim Taleb which shared a memorable quote that the best way to learn a language is to spend a night in a local prison (though much more extreme, but you get the point) — I decided to take the role at the Ministry of Education.

In my mind, though it was a relatively unconventional career move that introduced questions from my surroundings (my Dad asked me: “Isn’t moving back to a high-track corporate career going to be difficult after this?”), I decided that the risk-reward was worth it. First, I was not taking any salary risk. Nadiem’s objective was to attract high-skilled members to join his special unit. Second, I positioned this move as a 1-2 year max commitment to do a unique form of public service that I wanted to do previously anyways (as part of the Teach for America program where one would be placed for 2 years in an under-funded school as a teacher). Third, I had all the safety nets already anyways: a Bain brand, a deferred acceptance to the Kellogg MBA program.

On the contrary, the rewards would be plenty: I would be undoubtedly exposed to a different environment that would push me to grow, be aligned to a core personal mission, and I would sharpen my product development skillsets alongside talented Indonesians who were previously on the leadership level at the biggest tech companies in Indonesia.

I deeply internalized and built my own personal risk-reward matrix. To quote Aaron Brown—a legendary Morgan Stanley derivatives trader and poker expert—from his extraordinary book The Poker Face of Wall Street, when talking about hiring traders at an investment bank:

“What I listen for is someone who really wanted something that could be obtained only through taking the risk, whether that risk was big or small.

It’s not even important that she managed the risk skillfully; it’s only important that she knew it was there, respected it, but took it anyway.

Most people wander through life, carelessly taking whatever risk crosses their path without compensation, but never consciously accepting extra risk to pick up the money and other good things lying all around them.

Other people reflexively avoid every risk or grab every loose dollar without caution.

I don’t mean to belittle these strategies; I’m sure they make sense to the people who pursue them. I just don’t understand them myself.

I do know that none of these people will be successful traders.”

In the Ministry of Education, I was involved as part of two main teams in a 100+ person Product Organization: the Product Strategy and the Educator Platform teams. In essence, I was responsible for building collective best practices for Product throughout the organization, helping shape the core product strategy within a key area of focus in education (which happened to be the K-12 educator vertical), and leading my own product within the vertical centered on content sharing and curation (imagine a niche YouTube but for content dedicated for educators to share how to teach), within a platform of already 3+ million teachers registered.

Skill-set building was one part of the equation. Similar to Bain, I sharpened my core Product skillsets at GovTech. From tactical discovery research and prioritization through opportunity trees, running Google Ventures’ inspired design sprints, UX mapping, experimental design and multivariate testing, machine learning design, GTM/launch preparation, and of course writing lots of PRDs, convincing a lot of engineers and designers to execute on the given plan, and communicating progress to leadership — I learned quickly how to be a versed Product Manager. It helped that there were so many available resources online, from books, to Reforge / Maven. The amount I learned was affirming that there was so much important skill-set building that I would not be developing at Bain, and hence affirmed that I made the right decision.

Immersion to Indonesia was another one core part of my experience. To overcome my non-existing Indonesian language abilities, I took language lessons 4-5 times a week, 2 hours apiece. I remember my teacher made fun of me, and said I was the first Indonesian that she ever had to teach. I pushed myself to learn through business content, listening to Gita Wirjawan’s Endgame from front to back, and making sure I translate and understand every part of their conversations. The content had the additional side-effect of making me incredibly tuned into and interested in the Indonesian entrepreneurial ecosystem. Slowly but surely, my Indonesian grew better and better. At the very least I could make myself make a bit of sense.

The ultimate immersion was partaking in meeting with leaders within the Ministry, and having to run the strategic planning sessions to finalize our roadmap. I broke the ice with the leaders and apologized for my broken Indonesian (“Ibu/Bapak, mohon maaf Bahasa Indonesia saya tidak lancar”). I joked around and told them I was taking lessons 5 times a week, and they all took it well joking back that I now had to teach them English for free. I remember these sessions particularly well because one of my initial big fears had been lifted.

And the growth in my ability to lead and direct sessions in Indonesian continued to develop. We took the team to Makassar & Bali to meet a diverse set of stakeholders in the education system from educators to school leadership. I helped design and conduct research sessions with very local Indonesian folks. This might sound so trivial and literally like a 8 year old child, but I was so proud when I completed solo interview sessions with a group of educators fully in Indonesian.

It was amazing to see my confidence continue to build, not only technically but also in my ability to lead teams and to communicate to external stakeholders in traditional Indonesian environments. Language is a necessary tool to build strong leadership, and I had finally demonstrated my ability to wield it. This would of course ultimately be necessary in the roles I had next.

Ultimately though, there was a realization that I could not shake. During a solo immersion at a Bali school (where I wanted to spend one week to fully be present to observe teachers teach and conduct lesson planning), I had the opportunity to build a relationship directly with some educators. They had opened up to me that all of this curriculum revamp that the Ministry of Education was pushing was fine, but the biggest personal challenge they faced was the fact that they were barely being paid. Many teachers had to take side jobs (tutoring, retail) to make ends meet. Many were under financial distress, and they shared how some were late on loan payments (which is factually true, as teachers are the profession most entangled in predatory online lending).

One story struck me in particular, which was when one teacher shared with me that their salary growth was pretty much non-existent. In order to be bumped up from one level to the next, they had to do a thesis that was completely unrelated to their day-to-day job and performance. And even if they successfully passed, their pay raise would be an increase of $30-40 per month. No one under these circumstances would want to go through the hassle of testing for the next stage. They instead chose to just prioritize their side jobs. This meant less time spent putting in extra work to care for students.

It was this fundamental realization that made me realize that doing all this work from the Ministry to improve curriculum and empower teachers to learn from each other, missed a core point. These teachers didn’t even have the time to do all this extra learning. Teaching should not be seen as a “noble profession”. These teachers also had lives, and families to take care of, and could barely financially sustain themselves. Meanwhile, their only lifeline at times due to Indonesia’s long one-month cash salary cycle was loans, which they could often only get from high-interest rate online providers given their low incomes.

A core problem that needed to be tackled, I reasoned, before all of this technology and educational curriculum initiatives could make a meaningful, at-scale difference to teacher’s lives — was to tackle the financial access problem. And this realization broadened beyond teachers, when I was reminded of how my student Jasmine’s family could not get a long-term loan at a bank to cover her payment to go to university abroad. Financial access, the problem of money, was massive and likely affected everything. People could not seize opportunities. People got into financial distress due to circumstances out of their control like emergencies and illnesses, and could not dig themselves out of these situations.

This problem, I realized, was the most important problem I needed to be part of solving. I was nearing my one-year planned commitment in the Ministry of Education, and the clarity of understanding of what I wanted to spend the next part of my life solving became sharper and sharper.

Interestingly, rather than my investment banking Dad pushing me into the field, I became keen to understand and contribute to finance due to the problems I saw on the ground. I didn’t know yet how I could partake in solving these problems, but I continued researching into and learning about the financial services space, the ecosystem and challenges, and kept my eyes open.

And, serendipitously, as God I realized often does once you put your head to something: put an opportunity in front of me.

I was reached out to by a friend to join as a Chief of Staff and Head of Product at Skor, a financial services startup that was aiming to build a unique platform: on one side a credit checking app similar to Credit Karma in the United States where consumers could check their credit scores and histories for free (a service that consumers could not easily access in Indonesia prior), and on the other side a next-generation credit card in a country where card penetration was then 2% that aimed to provide accessible, less expensive credit to millions through robust analytics (think Capital One, but in Indonesia).

It was exactly what I was looking for. Skor tackled a financial inclusion and literacy angle that I wanted to help solve, in a meaningfully differentiated way compared to other fintechs in the region. I would get exposure at the leadership level on how to build startups, and the role would involve both of the skillsets that I had sharpened: business and analytical chops at Bain, and product & operational chops at the Ministry of Education.

It so happened that the upcoming year was the final year I could defer my Kellogg MBA offer. And I rejected it, to help build Skor. Going back to the United States could wait, I was set on this mission. I accepted the offer at Skor, and without any sort of break, I jumped straight in.

Doubling down on Indonesia & mission to build financial access (Skor)

Joining Skor was a masterclass in exposure to startups and the financial services / credit ecosystem at a broad level. I worked the hardest I had ever worked at, and stressed the most I had ever stressed about at a job before. On the first day of the job, the founders walked me through the entire credit ecosystem, the intricacies of how credit data was stored and the key players (which I wrote about here), and the most important problems that Skor had to solve. It was still incredibly early in the company’s lifecycle, and many things were still yet to be figured out. However, I felt the early-stage excitement, the precipice before an incredible journey. It was the same feeling I felt at Cornerstone. And I told myself: I might not be a founder yet, but I would act like one.

My first task was to launch and manage Skorlife, the credit checking application. When I joined, we were in the process of convincing the credit bureau to work with us and had to build compliant operational processes and a regulatory framework. It was my first exposure to “compliance” and the high standards required to build a financial services product, and having to fulfill a number of requirements from ISO-27001 certification, sandbox approvals, down to user copywriting to get the necessary approvals for launch. At the same time, because we were handling consumer credit data with the mandate of helping consumers to understand their data: it was incredibly vital that the data was made incredibly easy to understand, and fundamentally accurate. Otherwise, thousands of customers could potentially complain about the inaccuracy of their files and the product could be shut down if it mislabeled certain information (e.g. a customer was late on a loan but in reality was not). However, the task of accuracy and ease of understanding was not a trivial task. Imagine having to transpose fields from datasets from the credit bureau that were originally made for professional credit analysts, into consumable information for consumers. Fields were non-standardized, and many online lenders even channeled loans from the balance sheets of banks and hence had their loan represented in their files coming from a creditor who they might not recognize. I pored over the details, every nook and cranny, to ensure that every information was encoded correctly.

Working together with the credit bureaus to launch Skorlife after months of effort, managing the intricacies of the integration across various vendors to properly onboard customers, and seeing the first users start to tick into the application post-Beta – it was an incredible feeling. Operating the platform was not without difficulty: having to continue managing compliance and the integrity of the systems. However, this was slowly but surely figured out. In parallel, I figured out the growth hacks, encoded the events dictionary and tracking that spanned the application, that would enable Skorlife to scale to 50,000+ downloads a day and to millions of consumers, leading to becoming #1 in the Indonesian App Store in both Android and iOS, and enabling Skorlife to win Google’s Best App for Social Good in 2023.

In parallel, I was supporting the build and launch of Skorcard, the next-generation credit card and card management application that would be a co-branded, highly integrated effort with a bank partner. When I joined Skor, they were still in the early stages of the journey of building the card, not having solidified the first bank partner yet. While it was the founders on the front lines driving this, I played a supporting role: sharpening the initial financial model to convince the bank partners on the long-term value creation of the partnership, codifying the PRD, the product flow and initial design across the end-to-end user experience, and identifying all of the core API integrations that were required. I joined all the bank meetings, and observed the rigor required to close a bank partnership from start to finish – a highly complex act that required us to build confidence and understanding across all divisions from Risk, Compliance, Business, Product, Technology. It was incredible to see milestones be accomplished: the bank partnership being closed, and progress towards launch accelerating.

And as Chief of Staff, I was able to listen to and partake in core company strategy conversations and helped out with the preparation of Board meetings, and attended them as well. I understood the level of rigor and trust that Skor’s founders had to build in order to secure investments from QED and Hummingbird in their second fundraising round. And I internaliz