So, what would this model look like in practice? We can take Polymarket as an example. Currently, the UMA protocol's tokens are used for dispute resolution, with the tokens tied to the dispute cases. The more markets there are, the higher the probability of disputes occurring, which directly drives the demand for UMA tokens. In a transaction-based model, the required margin can be a small percentage of the total bet amount, such as **0.10%**. If the total bet amount for a presidential election is $1 billion, this will generate $1 million in revenue for UMA. In a hypothetical scenario, UMA can use this revenue to buy back and burn its tokens. This model has its advantages, but also faces certain challenges, which we will discuss further later.

Another example of a similar model is MetaMask. To date, the embedded exchange function of the MetaMask wallet has processed over $36 billion in transaction volume, with the revenue from this alone exceeding $300 million. The same logic applies to staking service providers like Luganode, where their revenue is based on the scale of users' staked assets.

However, in a market where the cost of API calls is increasingly decreasing, why would developers choose one infrastructure provider over another? Why would they be willing to share revenue with an oracle service? The answer lies in network effects.

A data provider that can support multiple blockchains, provide unparalleled data granularity, and index new chain data faster will become the preferred choice for new products. The same logic applies to transaction-based service categories, such as intents or gas-free exchange solutions. The more blockchains supported, the lower the cost and faster the speed, the more likely it is to attract new products. This marginal efficiency improvement can not only attract users but also help the platform retain them.

Burn It All

The trend of linking token value to protocol revenue is not new. In recent weeks, several teams have announced mechanisms to buy back or burn their own tokens based on the revenue generated. Notable examples include Sky, Ronin, Jito, Kaito, and Gearbox.

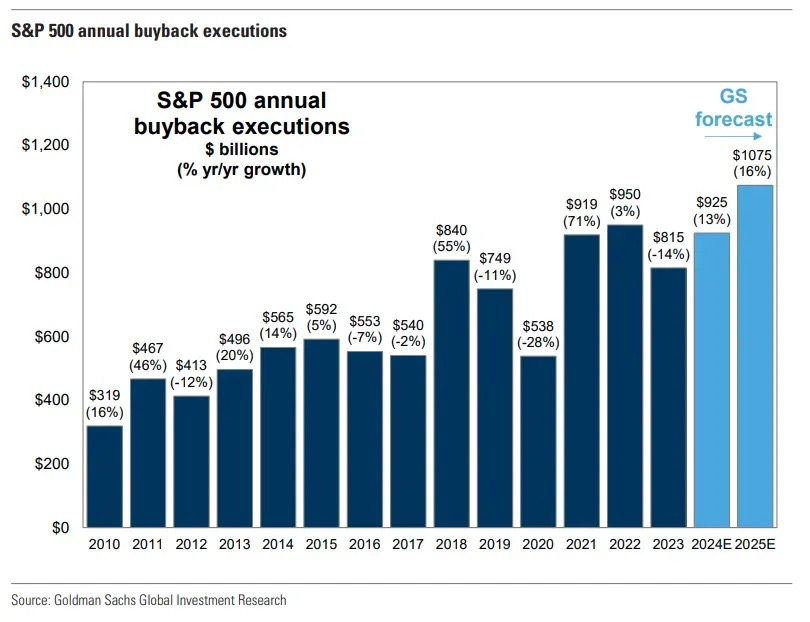

Token buybacks are similar to stock buybacks in the US stock market - essentially a way to return value to shareholders (in this case, token holders) without violating securities laws.

In 2024, the amount of stock buybacks in the US market alone reached $790 billion, compared to only $170 billion in 2000. Prior to 1982, stock buybacks were considered illegal. Apple has spent over $800 billion buying back its own stock over the past decade. Whether these trends will continue remains to be seen, but we can clearly see a bifurcation in the market: one set of tokens with cash flows and willing to invest in their own value, and another set with neither.

For most early-stage protocols or dApps, using revenue to buy back their own tokens may not be the optimal use of capital. One viable approach is to allocate sufficient funds to offset the dilutive effect of new token issuances. This is the explanation recently given by the founder of Kaito for their token buyback method.

Kaito is a centralized company that uses token incentives to engage users, receiving centralized cash flows from enterprise clients and using a portion of it to execute buybacks through market makers. The number of tokens bought back is twice the number of newly issued tokens, effectively putting the network in a deflationary state.

Another approach can be seen in the practice of Ronin. This blockchain dynamically adjusts fees based on the number of transactions per block. During peak usage periods, a portion of the network fees flows into Ronin's treasury. This is a way to control the asset supply without directly buying back tokens. In both cases, the founders have designed mechanisms to link value to network economic activity.

In future articles, we will delve deeper into the impact of these operations on token prices and on-chain activity. But for now, it is clear that as valuations decline and the risk capital flowing into the crypto space decreases, more and more teams will have to compete for the marginal dollars entering the ecosystem.

Since blockchains are inherently financial infrastructure, most teams will likely pivot to revenue models based on a percentage of transaction volume. When this happens, if they have already tokenized, they will have an incentive to implement a "buyback and burn" model. Those teams that can successfully execute this strategy will stand out in the liquid markets. Alternatively, they may eventually buy back their tokens at very high valuations. The actual outcomes of this situation can only be seen in hindsight.

Of course, one day, all discussions about prices, profits, and revenues may become irrelevant. Perhaps we will return to the era of throwing money at dog pictures or monkey NFTs. But for now, many founders struggling to survive have begun to engage in deep discussions around revenue and token burning.

Disclaimer:

1. This article is for reference only and does not constitute investment advice.

2. Individuals associated with Decentralised.co may hold investments in CXT.