Author: Shawn, Founder of Artichoke Capital; Translation: Jinse Finance xiaozou

Stablecoins are exciting. The upcoming stablecoin legislation in the United States is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to upgrade the financial system.

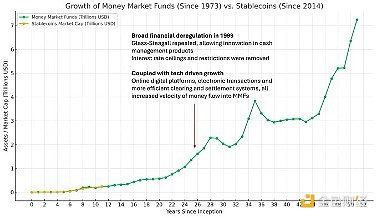

Financial historians will find that this is strikingly similar to the birth and development trajectory of money market funds about half a century ago.

Money market funds were invented in the 70s, primarily used as a cash management solution for businesses.

At the time, US banks were prohibited from paying interest on checking account balances, and businesses typically could not open savings accounts. If companies wanted to earn returns on idle funds, they had to purchase US Treasury bonds, enter into repurchase agreements, invest in commercial paper, or negotiable certificates of deposit. Managing cash required such a complex, high-touch process.

Money market funds used a constant share value structure, with each share pegged at $1.

Reserve Fund was the first money market fund, starting with $1 million in assets in 1971, positioned as a "convenient alternative for direct investment of temporary cash balances", typically investing in government securities, commercial paper, banker's acceptances, or certificates of deposit.

Subsequently, investment giants like Dreyfus (now Bank of New York Mellon), Fidelity Investments, and Vanguard quickly followed suit. In Vanguard's legendary mutual fund business growth in the 1980s, nearly half came from its money market funds.

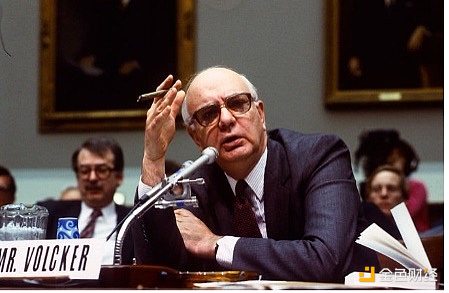

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker (in office 1979-1987) held a strongly critical attitude towards money market funds, maintaining his opposition until 2011.

Today, many criticisms from policymakers opposing stablecoins are identical to those against money market funds half a century ago:

* Systemic risk and threat to banking stability. Unlike insured deposit institutions (such as banks), money market funds lack deposit insurance and lender of last resort mechanisms, making them prone to runs and exacerbating financial instability and contagion risks. Some also worry that deposits flowing from insured banks to money market funds would weaken the banking sector by depriving banks of low-cost and stable deposit bases.

* Unfair regulatory arbitrage. Money market funds provide bank-like services by maintaining a stable $1 net asset value, yet are not subject to strict regulation or capital requirements.

* Weakening monetary policy transmission. As more funds flow out of the banking system into money market funds, traditional monetary policy tools like reserve requirements lose effectiveness, potentially undermining the Federal Reserve's monetary policy impact.

Today, money market funds hold over $7.2 trillion in financial assets. For reference, M2 money supply (basically excluding money market fund assets) is $21.7 trillion.

The rapid growth of money market fund assets in the late 90s stemmed from financial deregulation (the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act abolished the Glass-Steagall Act and triggered a wave of financial innovation), while the internet boom brought more efficient electronic trading systems, accelerating the flow of funds into money market funds.

Do you see the pattern? (It's worth noting that the regulatory debate over money market funds continues to this day, even half a century later. The US Securities and Exchange Commission passed a money market fund reform plan in 2023, including raising minimum liquidity requirements and removing managers' power to restrict investor redemptions.)