Today, Powell suddenly announced that he was ready to stop balance sheet reduction.

What did he see!?

Powell's main motivation

Powell's primary motivation for stopping balance sheet reduction is to prevent a liquidity crisis in the financial markets.

Powell mentioned in his speech:

Some signs have begun to emerge that liquidity conditions are gradually tightening, including a general firming in repo rates and more pronounced, but temporary, pressures on specific days. The Committee's plan lays out a prudent approach to avoid the kind of money market strains that occurred in September 2019.

What does this sentence mean?

Let’s take a look at a picture to find out.

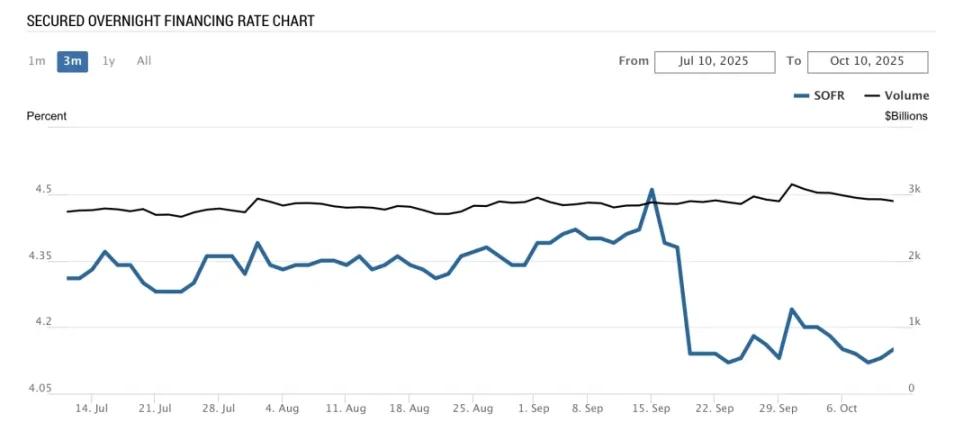

Figure: SOFR

The Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) shown in the chart above is one of the most important short-term interest rates globally today and represents the core "repo rate" mentioned in Powell's speech. (Starting in 2022, the Federal Reserve will promote SOFR as a replacement for LIBOR; trillions of dollars in loans, bonds, and derivatives are now priced using SOFR.)

SOFR is the actual transaction rate for overnight repurchase (repo) transactions using U.S. Treasury securities as collateral.

Simply put, financial institutions use U.S. Treasury bonds as collateral to borrow cash from other institutions overnight. The average interest rate of this "collateralized short-term loan" is SOFR.

So what is the relationship between SOFR and the Federal Reserve’s policy interest rate FFR?

The Federal Reserve's policy interest rate FFR (Federal Funds Rate) is an artificially set interest rate range, which the Federal Reserve controls through an upper and lower interest rate corridor: ON RRP (reverse repurchase rate) is the lower limit of the interest rate corridor, and IORB (interest on bank reserves) is the upper limit.

The current policy interest rate of the Federal Reserve is 4.00%-4.25%, which actually means setting the ON RRP (reverse repurchase rate) to 4.00% and the IORB (bank reserve interest) to 4.25%.

So how does the Federal Reserve keep the policy interest rate within the interest rate corridor?

First, let’s look at the upper limit of IORB (interest on bank reserves): banks have reserve accounts at the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Reserve will pay interest on these reserves (currently 4.25%), so banks have no reason to lend money to other banks at an interest rate lower than 4.25%, which creates an interest rate ceiling.

Let's look at the lower limit of the ON RRP (reverse repo rate): ON RRP stands for Overnight Reverse Repo. While money market funds and other institutions cannot hold reserves (reserves are the exclusive domain of banks), they can participate in the Federal Reserve's reverse repo facility: by lending cash to the Fed overnight, the Fed uses Treasury bonds as collateral and earns a safe interest rate of 4.00%.

Since I can earn 4.00% annual interest from the Federal Reserve, I have no incentive to borrow money below this rate. Therefore, no market interest rate can be lower than the ON RRP rate for a long time.

SOFR is the interest rate at which institutions trade with each other in the market, not the interest rate with the Federal Reserve.

In theory, the Federal Reserve's interest rate corridor mechanism (IORB upper limit + ON RRP lower limit) should firmly "clamp" all short-term market interest rates (including SOFR). This is because if SOFR < 4.00%, everyone will do ON RRP. If SOFR > 4.25%, banks will release the large amount of reserve funds deposited at the Federal Reserve to earn more interest (because deposits at the Federal Reserve only have a return of 4.25%), thereby suppressing yields.

But the problem is that if banks’ reserves are no longer sufficient and the funds they have placed with the Federal Reserve cannot be used for arbitrage temporarily, or if there is not enough money available for “arbitrage” to bring SOFR back below the IORB ceiling, the SOFR interest rate will temporarily break through the limit.

Once we understand this mechanism, the chart above makes it clear: Around September 15th, SOFR briefly crossed the 4.5% upper limit (at the time, the Fed's policy rate (FFR) was still between 4.25% and 4.5%). This is what Powell meant by "more pronounced but temporary pressures on specific dates."

After the interest rate cut, another "peak" appeared after September 29, which seemed to be very close to or even exceeded the new upper limit of 4.25% after the interest rate cut.

The main reason behind this phenomenon of market interest rates constantly "testing" or even breaking through the policy interest rate ceiling is that banks' reserves may no longer be sufficient due to various factors, so that when "arbitrage" opportunities arise in the market, there are no extra reserves to draw on.

This situation occurred once in 2019:

At that time, between 2017 and 2019, the Federal Reserve was carrying out the last round of quantitative tightening (QT), which resulted in the bank system's reserve balance (reserves) falling from about US$2.8 trillion to around US$1.3 trillion; at the same time, the US Treasury expanded its bond issuance scale, and a large amount of treasury bond issuance absorbed market cash; coupled with the overlap of corporate tax payments at the end of the quarter and treasury bond settlement dates, the market's short-term cash was instantly drained.

At that time, the liquidity in the banking system "seemed to be abundant", but in fact it had been pushed to the edge of safety.

On Monday, September 16, 2019, a series of events converged: companies paid their quarterly taxes (businesses removed cash from their bank accounts → reducing bank reserves); the Treasury settled a large Treasury bond issuance (investors paid the Treasury → bank reserves further decreased). The result was a sudden drop of approximately $100 billion in reserves in the banking system.

On that day, SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) jumped from 2.2% to 5.25%; the overnight repurchase rate (repo rate) soared from about 2% to over 10% overnight; banks and securities firms could not borrow cash, repurchase transactions were almost frozen, and a typical "liquidity stampede" occurred.

This is what Powell said in his speech:

The Committee’s plan lays out a prudent approach to avoid money market strains like those that occurred in September 2019.

At that time, the Federal Reserve was basically working overtime in the early morning to deal with the crisis. The New York Fed took emergency action in the early morning of September 17: it restarted overnight repurchase operations and injected $53 billion in cash that day to ease liquidity in the repurchase market. It continued to inject liquidity in the following days, with a total scale of more than $70 billion per day. At the same time, it urgently announced a temporary halt to balance sheet reduction and began to expand its balance sheet.

It’s clear that Powell doesn’t want to repeat this nightmare. The Fed’s long-term plan is to stop shrinking its balance sheet when bank reserves are “just above” the level considered “ample.”

Powell judged that "it is possible to approach this level in the coming months."

This means that from a technical perspective, balance sheet reduction has already approached its intended target, and continuing it could lead to excessive reserve scarcity, thus triggering systemic risks.

Secondary motives

In addition to the above main motivations, Powell also emphasized in his speech: "The downside risks to employment appear to have increased," and described the labor market as "lack of vitality and slightly weak."

This also brought some comfort to the market: while stopping the balance sheet reduction itself is not a direct interest rate cut or stimulus policy, it removes a factor that continues to tighten financial conditions. When the economy (especially the job market) shows signs of fatigue, continuing to implement tightening policies will increase the risk of recession.

Therefore, stopping the balance sheet reduction is a preventive and more neutral policy stance shift aimed at providing a more stable financial environment for the economy and avoiding "inadvertent damage" to the economy due to excessive policy tightening.

Finally, Powell also mentioned:

Our thinking is inspired by recent events in which signals of balance sheet reduction triggered a significant tightening of financial conditions. We are thinking of the events of December 2018 and the “taper tantrum” of 2013.

At that time, the mere signal of reducing asset purchases caused severe turmoil in global financial markets, which shows that the Fed is now extremely cautious in communicating with the market about its balance sheet operations.

Therefore, releasing the signal that "balance sheet reduction will stop" in the next few months in advance will give market participants sufficient time to digest this information and adjust their portfolios.

This clear and predictable communication approach aims to smoothly complete the transition from tightening to neutral policy and avoid unnecessary market volatility caused by sudden policy shifts. This is itself an important means of managing market expectations.