I just spent a week at the Consumer Electronics Show, and one word keeps popping into my head: bullshit.

LG, a company known for manufacturing home appliances and televisions, showcased a robot (named "CLOiD" for some reason) that claims to be able to "fold clothes" (very slowly, in limited circumstances, and sometimes even fail), cook (I mean put things into an automatically turning oven), or find your keys (in the video demonstration), but they have no intention of actually releasing this product.

The media generally gave it a lenient review, with one journalist even suggesting that the barely functioning technology demonstration " marked a turning point " because LG is now "entering the robotics field" with a product they have no intention of selling.

So why did LG showcase this robot? To deceive the media and investors, of course! Hundreds of other companies have also displayed robots you can't buy, and while the reports may say so, what we're seeing isn't "the future of robots" on any meaningful level. What we're seeing is what happens when companies lack creativity and can only copy each other. The 2026 Consumer Electronics Show being called "The Year of Robots" is like someone sitting in a cardboard box wearing a captain's hat and calling themselves a sailor.

However, compared to the absurd wave driven by large language models, robotics companies are surprisingly ethical: from obscure little firms in the basement of the Venice Expo to companies like Lenovo that incessantly talk about their " AI super agents ." In fact, screw it, let's talk about this.

"AI is evolving and gaining new capabilities, perceiving our three-dimensional world, and understanding how things move and connect," said Lenovo CEO Yang Yuanqing , before introducing the Lenovo Qira demonstration and claiming that it "redefines the meaning of technology built around you."

People would expect the next presentation to be a stunning demonstration of future technology. Instead, a speaker went on stage and asked Qira to show what it could see (i.e., multimodal capabilities that have been available in many models for years), received notification summaries (available in almost any large language model ensemble and extremely easy to hallucinate), and asked, "What should I buy for my kids when I have time?" At this point, Qira told her, and I quote, "There are some Labuus at the Las Vegas Fashion Mall that kids will go crazy for," referring to the kind of tool-based web search that has been available since 2024.

The presenter pointed out that Qira can also add reminders, which has been available on most iOS or Android devices for years, as well as file search, and then showcased a concept wearable device that can record and transcribe meetings, a product I've seen at least seven times during CES.

Lenovo rented the entire Las Vegas sphere to showcase a damn chatbot powered by an OpenAI model on Microsoft Azure, and everyone acted like it was something new. No, Qira wasn't a "big bet" on AI—it was just a chatbot crammed onto anyone who bought a Lenovo computer, full of "summarize this" or "transcribe this" or "tell me what's on my calendar," peddled by business idiots who have no experience with the practical application of almost anything, marketed with the kind of knowledge the media would struggle to explain why anyone should care.

Want better movies or audio from your TV? Forget it! What you get is Google's nano banana image generation and Samsung's other large language model capabilities.

You can now use Google’s Nano Banana model to generate images on your TV—a useless idea peddled by a company that doesn’t know what consumers really want, packaged to make your TV assistant “ more helpful and visually appealing .” As David Katzmaier rightly put it, nobody’s asking for a large language model to be installed in their TV so you can “click to search” for things on the screen; that’s not something a normal person would do.

In fact, most trade shows feel like companies playing a fill-in-the-blank game with startup presentations, trying to trick people into thinking they've done something, rather than just nailing a front-end interface to a large language model. The most obvious example is the plethora of useless AI-powered "smart" glasses, all claiming to be able to translate, dictate, or run "applications" with cumbersome, ugly, and difficult-to-use interfaces, all using the same large language model, and all doing essentially the same thing.

These products exist simply because Meta decided to invest billions of dollars in "AI glasses ," and a bunch of copycats are described as "part of a new category," rather than "a bunch of companies making a bunch of useless crap that nobody wants or needs."

This isn't the behavior of companies genuinely afraid of making mistakes, let alone the judgment of the media, analysts, or investors. This is the behavior of the tech industry, which, under the guise of "giving them a chance" or "being open to new ideas," evades any meaningful criticism of its core business or new products—not to mention regulation!—and these are ideas that the tech industry has just said, even if they are meaningless.

When Facebook announced its rebranding as Meta as a means to pursue its ambition of becoming the "successor to the mobile internet," it offered little evidence beyond a series of utterly terrible VR apps. But don't worry, Platform's Casey Newton was there to tell us that Facebook was "striving to build a maximized, interconnected set of experiences directly from science fiction: a world called the metaverse," adding that the metaverse was "all the rage." Similarly, Futurum Group's Dan Newman stated in April 2022 that "the metaverse is coming" and "is likely to continue to be one of the biggest trends in the coming years."

But three years and $70 billion later, the metaverse died, and everyone acted as if it had never happened.

Good heavens! In a rational society, investors, analysts, and the media would never again believe a word Mark Zuckerberg utters. Instead, the media eagerly reported on his mid-2025 blog post on "Personal Superintelligence," in which he promised everyone would have a "personal superintelligence" to "help you achieve your goals." Can large language models do that? No. Can they? No. That's okay! This is the tech industry.

No punishment, no consequences, no criticism, no skepticism, and no retribution—only celebration and reflection, only growth.

Meanwhile, the biggest tech companies continue to grow, always finding new ways (primarily through aggressive monopolies and massive sales teams) to boost numbers, to the point that the media, analysts, and investors have stopped asking any challenging questions and have naturally assumed that they—and the financiers who back them—would never do anything truly foolish.

The technology, business, and financial media are now well-trained to understand that progress is always the main theme of the story, and that failure is somehow "necessary for innovation," regardless of whether anything is innovative or not.

Over time, this has created evolutionary problems. The success of companies like Uber—reaching near-profitability after burning through billions of dollars for over a decade—has convinced journalists that startups must burn through massive amounts of money to grow . Convincing certain media members that something is a good idea only requires $50 million or more in funding, and larger funding rounds make criticizing a company less appealing because of the fear of "betting on the wrong winner," because the assumption is that the company will go public or be acquired, and nobody's wrong, right?

This naturally creates a world of venture capital and innovation, a nightmare of growth at all costs in a corrupt economy. Startups are rewarded not for creating a real business, or having a good idea, or even creating a new category, but for their ability to play the role of " brainwashing venture capitalists ," either by becoming "founders worth betting on" or by attracting the next multi-billion dollar potential market-sized scam.

They might find some product-market fit, or grow a large audience by offering services at unsustainable costs, but all of this is done knowing that they are about to receive a bailout through an IPO or acquisition.

Stagnation of venture capital

For years, venture capital has been rewarded for funding “big ideas,” and in most cases, it has paid off. Eventually, those “big ideas” have ceased to be “big ideas for essential companies” and have become “big ideas that grow as fast as possible and are dumped on the open market or by other companies that are afraid of being left behind.”

Taking a company public used to be easy [with over 100 IPOs per year from 2015 to 2019, and a continuous stream of mergers and acquisitions providing a place for startups to sell themselves], until the overblown bubble in the M&A and IPO market in 2021 (that year also saw $643 billion in venture capital investment), resulting in 311 IPOs losing 60% of their value by October 2023. Years of foolish bets based on the assumption that the market or large tech companies would buy any company that slightly frightened them have piled up.

This has created the current liquidity crisis in venture capital. Funds raised since 2018 have struggled to return any money to investors , making investing in venture capital firms less profitable. This, in turn, makes it more difficult to raise funds from limited partners, which in turn reduces the amount of capital available to startups, which are now paying higher rates because SaaS companies—some of which are startups—are extracting more money from customers each year.

These issues all boil down to one simple thing: growth. Limited partners invest in venture capitalists who demonstrate growth, and venture capital investments in companies that demonstrate growth, which in turn increases their value, allowing them to be sold for a higher price. Media coverage of companies is not based on what they do, but on their potential value, which is primarily determined by the company's atmosphere and the amount of money they raise from investors.

All of this only makes sense when there is liquidity, and based on the overall TVPI (total profit per dollar invested) of funds raised since 2018, most venture capital firms have not been able to earn more money for investors than the principal over the years.

Why? Because they're investing in bullshit. It's that simple. They're investing in garbage companies that will never go public or be sold to anyone else. While many people think of venture capital as making early, high-risk bets on nascent companies, the truth is that most venture capital is invested in later-stage bets . A more affable person might describe this as "doubling down on established companies," but we who live in the real world see it as its essence: a culture more akin to investing in stocks than understanding any business fundamentals.

Perhaps I'm being a bit naive, but my understanding of venture capital is that it's about discovering emerging technologies and giving them the means to realize their ideas. The risk is that these companies are in their early stages and therefore may fail, but those that don't fail will grow rapidly. Conversely, Silicon Valley waits for angel investors and seed investors to take the risk first, or spends all day scrolling through Twitter to find the next thing to pour in.

The problem with such a system is that it naturally rewards fraud, and the emergence of a certain technology is inevitable, which will counteract a system that has already driven out any good judgment or independent thinking.

Generative AI lowers the barrier to entry for anyone to cobble together a startup that can say all the right things to venture capitalists. Atmosphere coding can create a "working prototype" of a product that cannot be scaled (but can raise funds!), and the ambiguity of large language models—their voracious demand for data, huge data security issues, and so on—offers founders the opportunity to create a plethora of companies with ambiguous "observability" and "data authenticity." The heavy cost of running anything adjacent to large language models means that venture capitalists can make huge bets on companies with inflated valuations, allowing them to arbitrarily increase the net asset value of their holdings as other desperate investors flood into subsequent rounds.

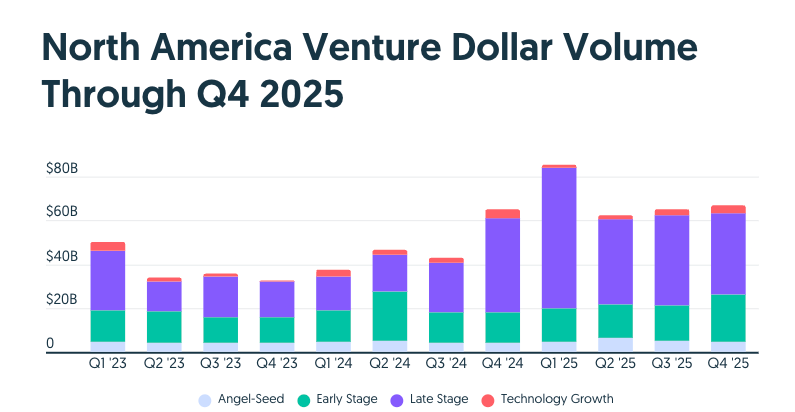

As a result, AI startups accounted for 65% of all venture capital funding in the fourth quarter of 2025. This fundamental disconnect between venture capital and value creation (or reality) has led to hundreds of billions of dollars flowing into AI startups that are already operating at negative profit margins. As their customer base grows, profit margins will worsen, and inference costs (creating output) are increasing. At this point, it becomes clear that it is impossible to create a profitable basic lab or a large language model-driven service, and renting GPUs for AI services also appears unprofitable.

I also need to make it clear that this is far more serious than the dot-com bubble.

US venture capital invested $11.49 billion in 1997 (equivalent to $23.08 billion in today's currency), $14.27 billion in 1998 (equivalent to $28.21 billion in today's currency), $48.3 billion in 1999 (equivalent to $95.5 billion in today's currency), and over $100 billion in 2000 ($197.71 billion), totaling $344.49 billion (in today's currency).

This is only $6.174 billion more than the $338.3 billion raised in 2025 alone, with about 40% to 50% (about $168 billion) going into AI investments. In 2024, North American AI startups raised about $106 billion.

According to the New York Times , "48% of internet companies founded since 1996 were still around at the end of 2004." The companies that collapsed during the 2000 bubble were primarily dubious and clearly unsustainable e-commerce stores like WebVan ($393 million in venture capital), Pets.com ($15 million), and Kozmo ($233 million), all of which had filed for IPOs, although Kozmo failed to bring itself to market in time.

However, in a very real sense, the "dot-com bubble" that everyone experienced had little to do with actual technology. Investors in the public market blindly rushed in with their wallets, investing in any company that even smelled like a computer, causing virtually any major technology or telecommunications stock to trade at absurd multiples of its earnings per share (60 times in Microsoft's case).

When the dot-com bubble burst and the world realized that the magic of the internet wasn't a panacea for every business model, the bubble burst, and there was no magic moment that could turn a terrible, unprofitable business like WebVan or Pets.com into a real business.

Similarly, companies like Lucent Technologies were no longer rewarded for engaging in dubious circular transactions with companies like Winstar, contributing to the collapse of the telecom bubble. This led to the cheap sale of millions of miles of dark fiber in 2002. The oversupply of dark fiber was ultimately seen as positive, causing demand to surge as billions of people went online in the late 2000s.

Now, I know what you're thinking. Ed, isn't this exactly what's happening here? We have overvalued startups, we have multiple unprofitable, unsustainable AI companies promising to go public, we have overvalued tech stocks, and we have one of the largest infrastructure projects in history. Tech companies are trading at absurd multiples of their earnings per share, but not that high. That's great, isn't it?

No. Not at all. AI proponents and well-intentioned individuals are obsessed with making this comparison because saying "things got better after the dot-com bubble" allows them to justify doing stupid, destructive, and reckless things.

Even if this were like the dot-com bubble, the situation would be absolutely damn catastrophic: the Nasdaq fell 78% from its peak in March 2000, but due to the incredible ignorance of the power brokers in the tech industry, I expect the consequences to range from catastrophic to devastating, depending almost entirely on how long the bubble takes to burst and how much the SEC is willing to approve IPOs.

The bursting of the AI bubble will be worse because the investment scale is larger, the contagion is wider, and the underlying asset, GPUs, is completely different from dark fiber in terms of cost, utility, and fundamental value. Furthermore, the fundamental unit economics of AI—both in its infrastructure and in the AI companies themselves—is far more alarming than anything we saw in the dot-com bubble.

To put it simply, I am really worried, and I am tired of hearing people make this comparison (referring to the internet in 2000 and the current AI bubble).