Author: Azuma

Original title: Why do banks insist on blocking stablecoin yields?

With Coinbase's temporary "reversal" and the Senate Banking Committee's postponement of its review, the Cryptocurrency Market Structure Act (CLARITY) has once again entered a period of stagnation.

Odaily Note: For background information, please refer to " The Biggest Variable in the Crypto Market: Can the CLARITY Bill Pass the Senate? " and " CLARITY Deliberations Suddenly Delayed: Why Are There Such Serious Divides in the Industry? "

Based on current market debates, the biggest point of contention surrounding CLARITY has focused on "interest-bearing stablecoins." Specifically, the GENIUS Act, passed last year, explicitly banned interest-bearing stablecoins in an effort to gain support from the banking industry. However, the act only stipulated that stablecoin issuers could not pay "any form of interest or yield" to holders, but did not restrict third parties from providing yields or rewards. The banking industry was very dissatisfied with this "circumvention" and attempted to overturn it in CLARITY by banning all types of interest-bearing paths, which has drawn strong opposition from some cryptocurrency groups, represented by Coinbase.

Why are banks so resistant to interest-bearing stablecoins and so determined to block all avenues for generating returns? This article aims to answer this question in detail by dissecting the profit models of major US commercial banks.

Bank deposit outflow? That's pure nonsense.

In arguments against interest-bearing stablecoins, the most common reason cited by banking representatives is "concern that stablecoins will cause an outflow of bank deposits." Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan stated in a conference call last Wednesday: "Up to $6 trillion in deposits (approximately 30% to 35% of all commercial bank deposits in the United States) could migrate to stablecoins, thereby limiting banks' ability to lend to the overall U.S. economy… and interest-bearing stablecoins could accelerate this outflow of deposits."

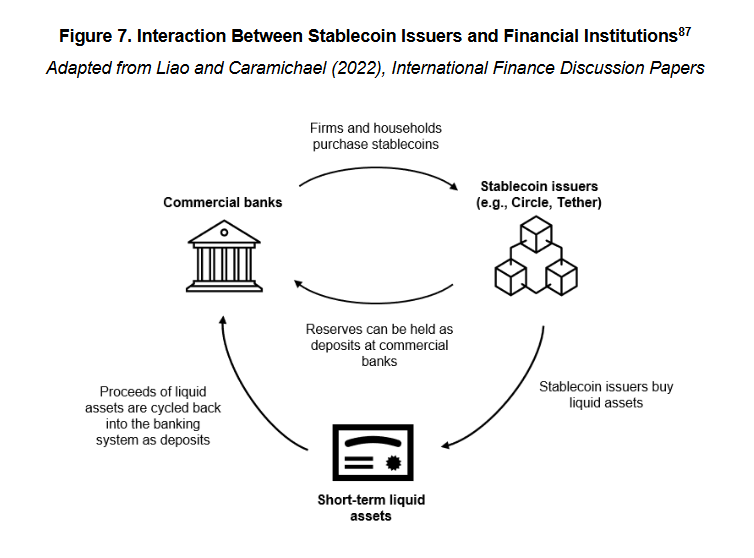

However, anyone with even a basic understanding of how stablecoins work can see that this statement is highly misleading and deceptive. When $1 flows into a stablecoin system like USDC, it doesn't disappear into thin air. Instead, it's placed in the reserve treasury of the stablecoin issuer, such as Circle, and eventually flows back into the banking system in the form of cash deposits or other short-term liquid assets (such as government bonds).

Odaily Note: Stablecoins with mechanisms such as crypto asset collateralization, futures-spot hedging, and algorithmic trading are not considered here. This is because such stablecoins represent a relatively small percentage of the market; and because they are not part of the discussion of compliant stablecoins under the US regulatory system—last year's GENIUS Act clearly stipulated the reserve requirements for compliant stablecoins, limiting reserve assets to cash, short-term Treasury bonds, or central bank deposits, and requiring segregation from operating funds.

Therefore, the fact is clear: stablecoins do not cause an outflow of bank deposits, because the funds will eventually flow back to banks and can be used for credit intermediation. This depends on the business model of stablecoins and has little to do with whether they generate interest.

The real key issue lies in the changes in the deposit structure after the funds flow back.

American banks' cash cow

Before analyzing this change, we need to briefly introduce the business model of major US banks.

Scott Johnsson, general partner at Van Buren Capital, cited a paper from UCLA stating that since the 2008 financial crisis damaged the banking industry's reputation, U.S. commercial banks have diverged into two distinct forms in their deposit-taking business—high-interest-rate banks and low-interest-rate banks.

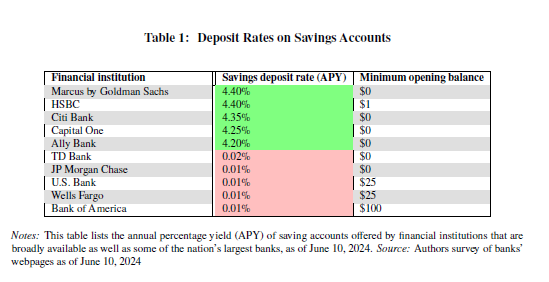

The terms "high-interest bank" and "low-interest bank" are not formal classifications in a regulatory sense, but rather common terms used in the market context. Superficially, this is reflected in the fact that the interest rate difference between high-interest banks and low-interest banks has reached more than 350 basis points (3.5%).

Why is there such a significant difference in interest rates for the same deposit? The reason lies in the fact that high-interest banks are mostly digital banks or banks with a business structure that focuses on wealth management and capital markets (such as Capital One). They rely on high interest rates to attract deposits to support their lending or investment businesses. Conversely, low-interest banks are mainly large national commercial banks such as Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo, which wield real power in the banking industry. They have a large retail customer base and payment network, and can maintain extremely low deposit costs by leveraging customer loyalty, brand effect, and branch convenience, without needing to compete for deposits through high interest rates.

In terms of deposit structure, high-interest banks generally focus on non-transactional deposits, which are mainly used for savings or to earn interest returns. These funds are more sensitive to interest rates and have higher costs for banks. Low-interest banks, on the other hand, generally focus on transactional deposits, which are mainly used for payments, transfers, and settlements. These funds are characterized by high stickiness, frequent turnover, and extremely low interest rates, making them the most valuable liabilities for banks.

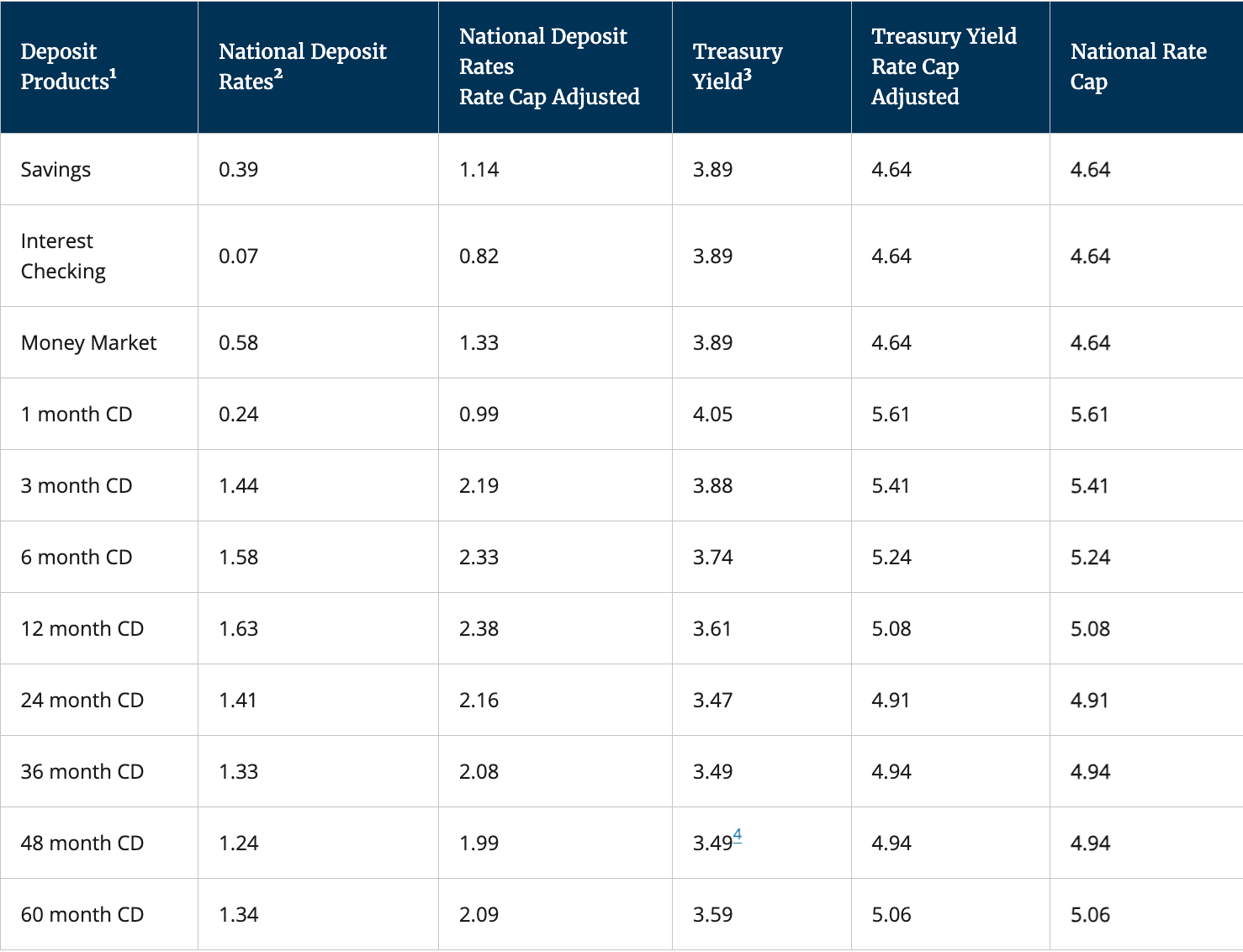

According to the latest data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), as of mid-December 2025, the average annual interest rate for U.S. savings accounts was only 0.39%.

Note that this data already accounts for the impact of high-interest banks. Since major U.S. banks operate on a low-interest-rate model, the actual interest they pay to depositors is far lower than this level. Galaxy founder and CEO Mike Novogratz stated in an interview with CNBC that large banks pay depositors almost zero interest (approximately 1-11 basis points), while the Federal Reserve's benchmark interest rate during the same period was between 3.50% and 3.75%. This interest rate differential brings huge profits to banks.

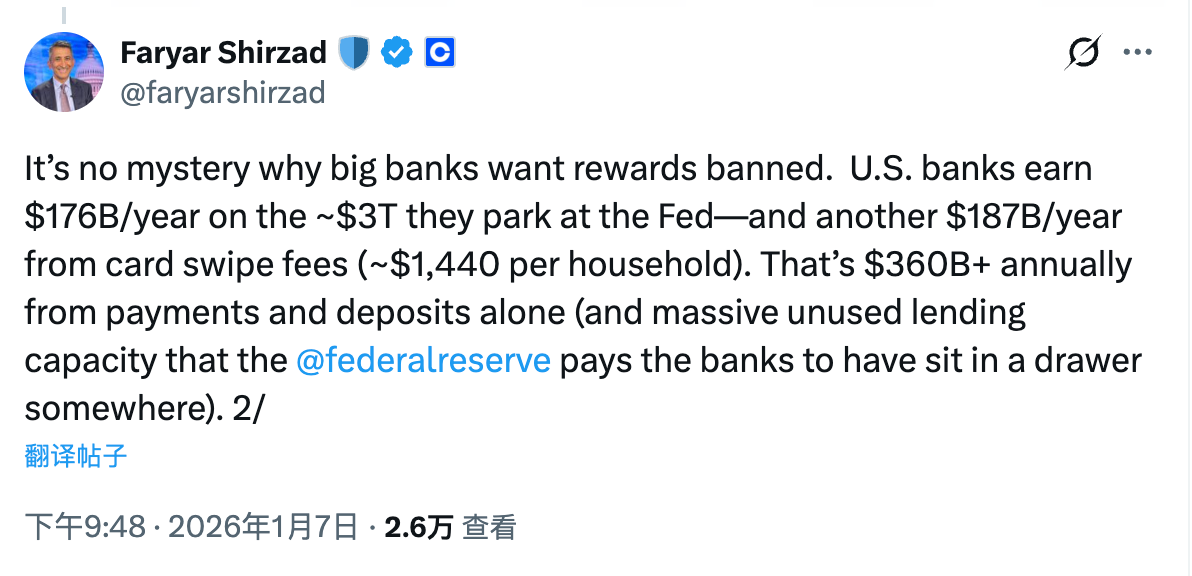

Coinbase's Chief Compliance Officer, Faryar Shirzad, provided a clearer breakdown of the figures: Major U.S. banks earn $176 billion annually from the approximately $3 trillion deposited with the Federal Reserve, plus an additional $187 billion annually from transaction fees collected from depositors. This translates to over $360 billion in revenue each year solely from deposit interest rate spreads and payment transactions.

The real change: deposit structure and profit distribution

Getting back to the main topic, what changes will stablecoin systems bring to bank deposit structures? And how will interest-bearing stablecoins further promote this trend? The logic is actually quite simple: what are the use cases for stablecoins? The answers are nothing more than payments, transfers, settlements…etc. Doesn't that sound familiar?

As mentioned earlier, these functions are precisely the core utility of transaction deposits, which are not only the main deposit type for major banks but also their most valuable liability. Therefore, the banking industry's real concern about stablecoins lies in the fact that, as a completely new medium of exchange, stablecoins can be directly compared to transaction deposits in terms of usage scenarios.

If stablecoins didn't offer interest-bearing capabilities, it wouldn't be a problem. Considering the barriers to entry and the meager interest rates of bank deposits (even a small amount is still an advantage), stablecoins are unlikely to pose a real threat to this core area of large banks. However, once stablecoins are given the possibility of earning interest, driven by interest rate spreads, more and more funds may shift from transaction deposits to stablecoins. Although these funds will eventually flow back into the banking system, stablecoin issuers, for profit reasons, will inevitably invest most of their reserves in non-transaction deposits, only needing to retain a certain percentage of cash reserves to handle daily redemptions. This is what's known as a change in deposit structure—while funds remain in the banking system, bank costs will increase significantly (interest rate spreads will be compressed), and revenue from transaction fees will also decrease substantially.

At this point, the essence of the problem is very clear. The reason why the banking industry is so vehemently opposed to interest-bearing stablecoins has never been about "whether the total amount of deposits in the banking system will decrease," but rather about the potential changes in the deposit structure and the resulting profit redistribution issues.

In the era before stablecoins, especially interest-bearing stablecoins, large U.S. commercial banks firmly controlled transaction deposits, a source of funds with "zero or even negative costs." They could earn risk-free returns through the interest rate spread between deposit rates and benchmark rates, and continuously collect fees through basic financial services such as payments, settlements, and clearing, thus building an extremely stable closed loop that required almost no sharing of returns with depositors.

The emergence of stablecoins essentially breaks down this closed loop. On the one hand, stablecoins are highly similar to transaction deposits in terms of functionality, covering core scenarios such as payments, transfers, and settlements. On the other hand, interest-bearing stablecoins further introduce the variable of yield, making transaction funds, which were originally not sensitive to interest rates, possible to be repriced.

In this process, the funds do not leave the banking system, but banks may lose control over the profits of these funds. What was originally a liability with almost zero cost is forced to become a liability that requires the payment of market-based returns; the payment fees that were originally exclusively held by banks are also being diverted to stablecoin issuers, wallets, and protocol layers.

This is the change that the banking industry truly cannot accept. Understanding this makes it easier to understand why interest-bearing stablecoins became the most intense and difficult point of contention in CLARITY's process of overcoming obstacles.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/BitpushNewsCN

BitPush Telegram Community Group: https://t.me/BitPushCommunity

Subscribe to Bitpush Telegram: https://t.me/bitpush