Author: Nicolas Vescovo

The BitVM framework was designed to bring optimistic verification of arbitrary off-chain computations to the Bitcoin network, allowing for more complex operations such as zk rollups and sidechain bridges. BitVM enhances Bitcoin's flexibility by introducing mechanisms that support optimistic verification. BitVMX, on the other hand, uses different techniques to enable faster and more efficient checking of certain operations, achieving even better results. In this context, "optimistic verification" refers to a verification method based on an assumption—that operations are valid unless it can be proven otherwise .

To ensure the security of such systems, BitVM and BitVMX use Lamport and Winternitz signatures. These cryptographic methods are key to ensuring the "statefulness" of the entire process. By using these signature schemes, BitVM and BitVMX provide robust security against a variety of attacks and guarantee that all operations are executed correctly.

This article explains what "Lamport signatures" and "Winternitz signatures" are, how the latter extends the concept of the former, and how they are used in BitVM. We will also explain how these signatures bring statefulness to BitVM and BitVMX, ensuring that once a specific variable is set, it cannot be modified or reused in subsequent scripts.

Understanding Lamport and Winternitz Signatures

An electronic signature scheme is a mathematical method used to verify the authenticity and integrity of electronic messages (or documents). Simply put:

- Lamport signatures use one-time electronic commitments (essentially based on hash functions) to provide signatures that cannot be forged.

- Winternitz signatures, on the other hand, use multiple iterations of a one-way function (often forming a chain) to achieve cryptographic security.

Lamport signatures , proposed by Leslie Lamport in the late 1970s, are a hash function-based electronic signature scheme. They leverage the one-way property of cryptographic hash functions for security. Lamport signatures are renowned for their simplicity and resistance to quantum computing attacks. The process involves pre-generating a large number of key pairs and then using them for signing. However, their large signature size may limit their applications.

Winternitz signatures , independently proposed by Ralph Merkle and Robert Winternitz, are another type of digital signature based on hash functions. They offer similar security to Lamport signatures but are more efficient. Compared to Lamport signatures, Winternitz signatures utilize a chain structure, reducing the signature size and making them more practical. By allowing users to adjust the Winternitz parameters, these signatures can achieve a balance between computational speed and signature size, essentially generalizing the Lamport signature scheme.

Lamport Signature: A Formal Perspective

In this chapter, we provide a step-by-step explanation of how Lamport signatures are generated, used, and verified. We explore the technical aspects of the key generation process, message signing, and signature verification. Finally, we discuss the related security considerations and vulnerabilities.

Key generation

For each bit i in the message that needs to be signed, generate two random strings (bit sequences), denoted as $S_{i, 0}$ and $S_{i, 1}$ respectively. If the message length is n bits, then the value of i ranges from 0 to $n-1$.

The private key is composed of these random string pairs $(S_{i, 0}, S_{i, 1})$ (where $i = 0, 1, …, n-1$).

For each pair of strings $(S_{i, 0}, S_{i, 1})$ in the private key, calculate the hash of these strings and keep them paired: $(H(S_{i, 0}), H(S_{i, 1}))$.

The public key is composed of these hash pairs $(H(S_{i, 0}), H(S_{i, 1}))$ (where $i = 0, 1, …, n-1$).

Signature message

Convert the message m to be signed into binary form, i.e., $m = m_0m_1…m_{n-1}$, where each $m_i$ is a bit (with a value of 0 or 1).

For each bit $m_i$ in the message, the signature contains the corresponding private key $S_{i, m_i}$.

Ultimately, the signature is a sequence of n elements: (S_{0, m_0}, S_{1, m_1},...,S_{{n-1}, m_{n-1}}) .

Verify a signature

Given a message m and its signature (S_{0, m_0}, S_{1, m_1},...,S_{{n-1}, m_{n-1}}) .

Convert message m to binary form: $m = m_0m_1…m_{n-1}$.

For each bit $m_i$, calculate the hash value of the corresponding element in the signature: $H(S_{i, m_i})$.

Verify that each calculated hash value $H(S_{i, m_i})$ matches the corresponding element in the public key ($H(S_{i,0})$ or $H(S_{i, 1})$.

Safety considerations

- Single-use : The Lamport signature scheme is secure only when each key pair is used to sign only one message. Using the same key pair to sign multiple messages reveals part of the private key, thus sacrificing security.

- Hash function : The security of the Lamport signature scheme depends on the strength of the cryptographic hash function used—it should be resistant to preimage attacks, second preimage attacks, and collision attacks.

Why are they called "one-time signatures"?

Lamport's signature scheme is known as "one-time signature" because its security drops drastically if the same public key is used to sign more than one message. This is because each additional message signed reveals more information about the private key, making it easier for attackers to forge signatures.

After observing one signature, an attacker knows the preimage of one hash value in every pair of hash values in the public key. However, with two signatures, an attacker knows the two preimages of half of the hash value pairs and one preimage of the other half. With three signatures, an attacker knows the two preimages of three-quarters of the hash value pairs; and so on. This gradual exposure means that the security of the same public key is effectively halved with each additional signature.

(Translator's note: The author used the assumption of random bit distribution in the previous paragraph.)

For example, if a public key is designed to provide 256 bits of security against second preimage attacks and 128 bits of security against collision attacks, a practical attack becomes possible after it has been signed three times. After it has been signed four times, finding the message-signature pairing becomes very easy. This vulnerability arises because an attacker can use a known hash (and its preimage) to construct a new valid signature for a message of their choosing; this is especially true in contexts where the message has some flexibility.

Lamport signature vulnerability when used more than once

The main vulnerability of Lamport signatures when used to repeatedly sign with the same public key lies in the fact that attackers can use information obtained from previously observed signatures to forge signatures for arbitrary messages. Suppose an attacker knows the signatures generated for multiple messages using the same public key. In this case, the attacker can combine the known signatures to construct a new, valid signature.

For example, consider a message with a length of 16 bits:

The signed messages are: m1 = 0001111101110001 and m2 = 0111110000111111. An attacker can forge a signature for a new message m * = 0101111000110101 by simply piecing together the corresponding parts of the signatures for the two messages above. Any m * constructed using the corresponding bits from m1 and m2 can forge a valid signature—a signature can be constructed simply by using the preimage of the hash values corresponding to these bits.

If the message is hashed before being signed (i.e., the signature is not the message itself, but its hash value), the attack becomes more complex, but still feasible. An attacker must find a message m * whose hash value shares a sufficient number of identical parts with the hash values of previously signed messages. Each additional observable signature reduces the number of hash function evaluations required for the attack, making forgery easier.

Essentially, when using the Lamport signature scheme, each public key should only be used once to maintain security. Reusing a single public key for signing multiple messages will allow an attacker to obtain enough information to forge new signatures, ultimately breaking the integrity of this cryptographic system.

Winternitz's signature: Theoretical perspective

As we've already discussed, Winternitz One-Time Signatures (WOTS) are an enhancement of Lamport signatures, significantly reducing the size of the signature and public key. However, there's no free lunch. This improvement comes at the cost of requiring more effort to generate and verify signatures. In this chapter, we'll provide a formal definition and explain how Winternitz signatures work.

Parameters and Startup

- W: The Winteritz parameter, a positive integer, determines the number of bits that can be processed at one time.

- n: The length of the hash output (in bits).

- l: The number of segments in the message digest, calculated as $l = \lceil n/W \rceil$. Here, $\lceil \rceil$ means taking the smallest integer greater than or equal to the given number.

- l': The length of the checksum, calculated as $l' = \lceil (\log_2(l * (2^W - 1)))/W \rceil$

- L: Total length of the signature, L = l + l'.

Key generation

Generate L random bit strings $S_i$ of length n, where $i = 0, 1, …, L-1.

The private key is composed of these random bit strings: $S = (S_0, S_1, …, S_{L-1})$.

For each private key fragment $S_i$, apply the hash function $2^W$ times consecutively: $P_i = H^{2^W}(S_i)$.

The public key is composed of these hash results: $P = (P_0, P_1, …, P_{L-1})$

Signature message

Divide the message m to be signed into l fragments of length W bits: $m = (m_0, m_1, …, m_{l-1})$.

Calculate the checksum C: $C = \sum_{i=0}^{l-1}(2^W - 1 - m_i)$.

Convert the checksum C into l' fragments of length W bits: $C = (c_0, c_1, …, c_{l'-1})$. Generally, the first element is used as the checksum: $C = (c_0)$.

For each fragment $m_i$ of the digest and the checksum $c_i$, generate a signature $\sigma_i$ by hashing the corresponding private key fragment $m_i$ times: $\sigma_i = H^{m_i}(S_i)$, where $i = 0, 1, …, l-1$.

Similarly, for the checksum part: $\sigma_{l+j} = H^{c_j}(S_{l+j})$, where $j = 0, 1, …, l'-1$.

The complete signature is a combination of these fragments: $\sigma = (\sigma_0, \sigma_1, …, \sigma_{L-1})$.

Verify signature

Given a message m and its signature $\sigma = (\sigma_0, \sigma_1, …, \sigma_{L-1})$.

Divide message m into l parts: $m = (m_0, m_1, …, m_{l-1})$.

Calculate the checksum C and divide it into l' parts: $C = (c_0, c_1, …, c_{l'-1})$.

For each signature fragment $\sigma_i$, apply the hash function $2^W - 1 - m_i$ times, hoping it will derive the public key fragment:

$$

P_i : \widehat{P_i} = H^{2^W - 1 - m_i}(\sigma_1) , \qquad i = 0, 1, …, l -1

$$

Similarly, for the checksum part:

$$

\widehat{P_{l+j}} = H^{2^W - 1 - c_{j}}(\sigma_{l+j}) , \qquad j = 0, 1, …, l' -1

$$

If the derived public key $(\widehat{P_0}, \widehat{P_1},…, \widehat{P_{L-1}})$ matches the public key $P = (P_0, P_1, …, P_{L-1})$, then it is a valid signature.

Safety considerations

- Parameter selection : The choice of W affects the trade-off between signature size and computational efficiency. A larger W value will reduce the signature size, but will increase the computational burden of signing and verification.

- Single-use : Like Lamport signatures, Winternitz signatures are also for single-use only. Reusing the same key pair in signing multiple messages will compromise security by revealing information about the private key.

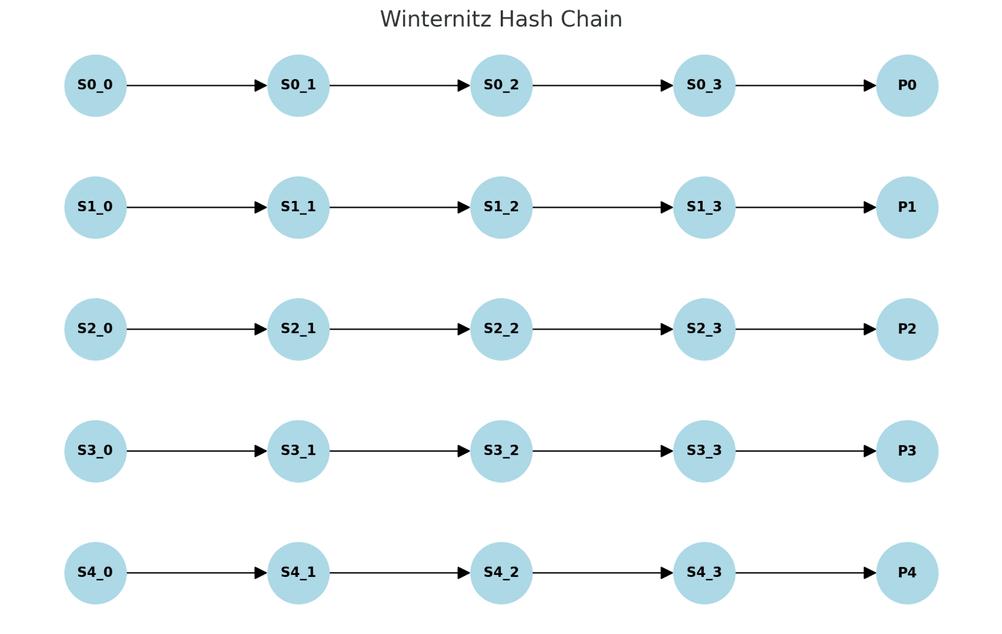

The diagram below illustrates the sequence of the Winderitz chain (deriving the public key from the private key) when W = 2 and l = 5. Each arrow represents a hash job search. (Translator's note: The original text here was incorrect and has been corrected.)

Why is a checksum necessary?

From a technical perspective, the checksum in the Winternitz signature scheme is necessary to maintain security and ensure the integrity of the signing process.

The Winternitz signature scheme works by dividing the message into fragments and then hashing the corresponding private key fragment a certain number of times based on the value of each fragment. However, this process introduces a vulnerability: if an attacker knows a signature (composed of values on the hash chain), they can use subsequent elements in the hash chain to construct a valid signature. This is because, by revealing just one member of the hash chain, an attacker can calculate all subsequent hash values (which are themselves signatures of the same private key fragment for a given value), thus breaking the integrity of the signature.

To mitigate this risk, checksums are crucial. They ensure that any modification to the message will result in a corresponding, consistent change to the checksum—a computationally infeasible operation without the private key. This is because using subsequent values in the hash chain requires knowing earlier values in the signature checksum's hash chain (which is impossible without the private key). The checksum acts as an additional layer of verification, preventing attackers without preimage capabilities from generating a valid signature for another message without knowing the private key.

(Translator's note: The reasoning here is that, since the hash chain is unidirectional, without considering the checksum, knowing a WOTS signature only allows an attacker to forge signatures for each larger $m_i$, i.e., using values later in the hash chain. However, using the aforementioned checksum $C = \sum_{i=0}^{l-1}(2^W - 1 - m_i)$, a larger $m_i$ will result in a smaller C. A signature with such a C would require using values earlier in the private key hash chain. Deriving this from a known signature would mean reversing the hash operation, which is computationally infeasible. Therefore, without the private key, it is impossible to create a signature.)

Furthermore, the checksum also ensures the integrity of the signing process. It is a final check to verify that no bit was omitted or replaced during the signing process. This guarantees that the entire message has been taken into account and is correctly represented in the signature.

Furthermore, the checksum also verifies the overall integrity of the signature. That is, the correct number of hash iterations was applied, thus ensuring that the signature is both accurate and secure.

Without a checksum, this scheme is highly vulnerable to attack. An attacker could easily replace message fragments and create a valid signature without the private key. The lack of a checksum can also lead to incomplete verification, allowing replaced or truncated messages to be treated as signed.

BitVM and BitVMX: Where Lamport's and Winternitz's signatures shine.

As we've already mentioned, BitVM and BitVMX are frameworks designed to bring optimistic verification of arbitrary off-chain computations to the Bitcoin network. Both can use Lamport signatures or Winternitz signatures to create robust data commitments. In this context, a commitment is a cryptographic guarantee that a specific piece of data existed, was securely recorded, and was signed at a certain point in time. These commitments can be invoked in future challenges from validators. The use of these signatures ensures that each commitment is verifiable and tamper-resistant.

If the verifier agrees with the operator, then nothing needs to be done and the operation will proceed normally; however, if the verifier disagrees with the operator, because both parties have publicly signed these commitments, the agreement allows both parties to use each other's information to prove that the other party is attempting fraud or performing an incorrect operation.

A key innovation of BitVM is its ability to maintain and reference state across multiple transactions. This is achieved by using a one-time signature to commit to the state at every step. By leveraging Lamport signatures, BitVM guarantees that every state transition is securely committed and can be reliably referenced in subsequent operations.

in conclusion

Lamport and Winternitz signatures possess a range of desirable properties that make them suitable for use in BitVM and BitVMX. Their integration into these protocols significantly enhances Bitcoin's scripting capabilities, enabling efficient and secure stateful operations. Their use in data commitments ensures the network can handle more complex transactions while maintaining security and performance. These cryptographic techniques are crucial to Bitcoin's future, paving the way for more advanced and secure decentralized applications, such as trust-minimized sidechain bridges and optimistically verified zero-knowledge proofs.

(over)