Author: NIKLAS GÖGGE

Source: https://brink.dev/blog/2026/01/07/fuzzamoto-introduction/

About a year ago, I started developing " Fuzzamoto ," a fuzz testing tool implemented as a full Bitcoin node. In this blog series, I'll share my experiences, indirections, and open questions encountered along the way. The first post will introduce the motivation behind creating the Fuzzamoto project and provide an overview of its design and architecture. In subsequent chapters, I'll delve into its determinism, test case generation and mutation testing, bugs discovered, feedback on fuzz tests that go beyond their coverage, and more.

motivation

To date, Bitcoin Core is the most widely adopted implementation of the Bitcoin protocol on the network, so its bugs can have disastrous consequences. This is also why Bitcoin Core has a very conservative development culture, which is necessary to some extent and an advantage (obviously a major reason why it doesn't have many serious bugs), but it can also lead to frustration, burnout, and slow progress on major projects.

Even if you simply want to improve testing, refactor existing code to make it easier to test, or add test items, you might face significant resistance. Resources for this project are extremely limited, and complex PRs hold no appeal for reviewers because a 20% speedup in initialization synchronization time, P2P protocol features, and other minor changes require less time and effort to review. To make matters worse, if you have to refactor the code to add more tests, the refactoring process itself could introduce bugs. This becomes a chicken-and-egg problem—testing reduces the risk of refactoring, but adding tests requires refactoring.

These refactorings typically decouple modules, splitting code into separate modules or adding interfaces to enable mocking, which is often necessary for in-process/persistent fuzzing. For example, if the component under test depends on disk I/O, fuzzing will be slow and scalable, so you would want to mock it (disk I/O) to speed it up.

At this stage, significant improvements to Bitcoin Core testing (discovering serious existing bugs or preventing bugs from escalating) are still highly likely. For example, the P2P code for validating blocks, transactions, and dense blocks has not been fuzz-tested, as have the more cohesive code paths related to chain reassembly and other similar processes. To efficiently test this code using traditional in-process controls, changes would be needed to critical code (consensus, P2P, etc.), code that has not received the necessary level of testing.

I can say that, from my personal experience, gaining support for these refactorings is painful, and I've lost interest in maintaining PRs for months or even years; the benefits of these refactorings often seem to be overshadowed by higher feature churn rates and minor changes.

In this context, Bitcoin Core will clearly benefit from testing that doesn't unnecessarily burden the conservative review process or require any changes to Bitcoin Core itself. Such testing can close remaining testing gaps and reduce future risks. The ultimate vision is an external testing tool that takes production-ready binaries as input and bugs as output.

Bitcoin Core's functional tests were once the closest thing to this idea because they generated complete nodes and tested them through the node's external interfaces (RPC, P2P, IPC, etc.). Writing functional tests didn't require refactoring; at most, it only required adding new RPC methods, allowing introspection of parts of the software's state. While these tests achieved high code coverage and uncovered a large number of bugs, they weren't property-based tests and didn't automatically expose edge cases. For example, a single-line patch for a functional test didn't find CVE-2024-35202 ; it was actually discovered through a refactoring and writing new fuzz tests (incidentally, these tests and refactorings were never merged into Bitcoin Core). If those functional tests had been property-based tests, perhaps they would have been able to find the problem.

After realizing this, I asked myself: Could we have "functional fuzz testing"? It shares the same testing concepts as functional testing, but instead of using hard-coded test scenarios and predetermined results, it uses fuzz testing to test attributes at the system level. This is the philosophy behind Fuzzamoto: fully-system, fuzz-driven simulation.

design

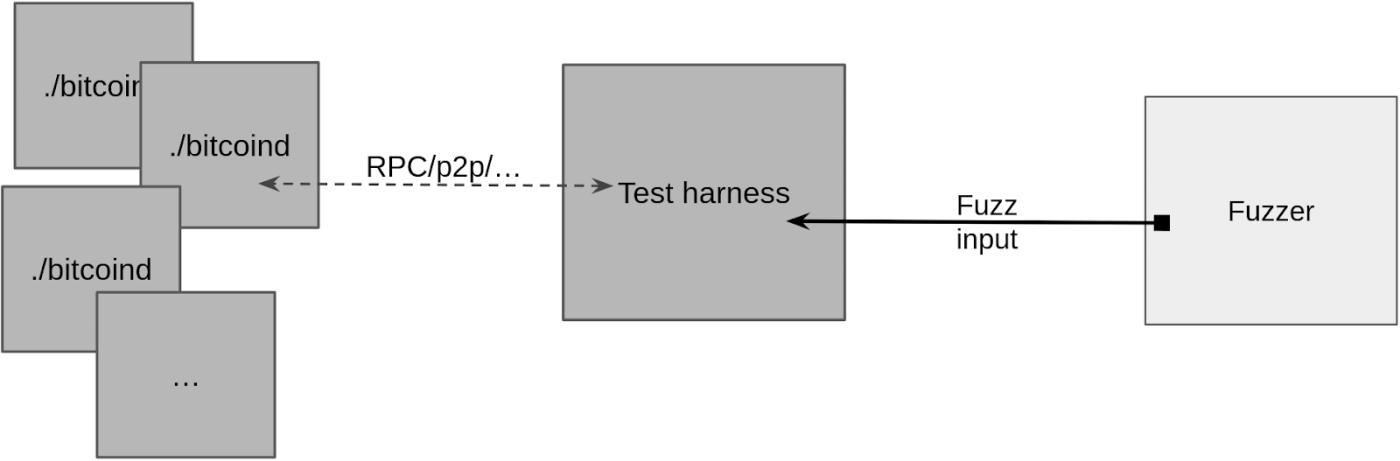

Abstractly speaking, fuzzing using Fuzzamoto consists of a full node background process (e.g., bitcoind, btcd, etc.) as the test target, a testing tool (which controls the execution of the test given a fuzzy input), and a fuzzing engine (used to generate the inputs provided to the tool for execution).

Snapshot Fuzz Test

One obvious challenge that needs to be addressed is that a naive implementation of this design can lead to the target node accumulating state after the fuzz test is executed (thus affecting subsequent tests), resulting in non-determinism. I will explore determinism and its challenges in more depth in later blog posts in this series, but in short: to make fuzz tests efficient, we want the execution of test cases to be deterministic, that is, given the same input, the test actions should be the same.

Fuzzamato solves this state problem using a fully systematic snapshot fuzzing approach. The principle is to run the target node and testing tools within a special virtual machine; this virtual machine is capable of generating a snapshot of all its states (memory, CPU state, devices, etc.) and quickly resetting itself to that state. Currently, Fuzzamato uses Nyx as the virtual machine backend, but theoretically, any backend with similar capabilities could work.

This allows us to avoid creating and tearing down the state every time (which is expensive). We can directly establish the required state at the beginning, then take a snapshot, start fuzzing, and quickly reset the virtual machine to the initial state at the end of each execution. Specifically, for fuzzing a Bitcoin full node, this allows us to (for example) pre-mine a blockchain and provide a mature (and immediately testable) coinbase output.

In the next post of this blog series, we will explain the technical details of Nyx: how it works, how Fuzzamoto uses it, and how coverage guidance works in this mode.

Scene

In Fuzzamoto, fuzzing tools can be called "scenes," which are responsible for establishing snapshot states, controlling the execution of fuzzy inputs, and reporting the results to the testing engine. Each scene needs to implement two functions:

- The creation of the scenario and the establishment of the snapshot state involve generating the target full node process and bringing the node to the state required to run the fuzz test.

- The execution of a test case means executing a test case in the state that was created earlier.

Testing HTTP servers, wallet migrations, RPC interfaces, and specific P2P protocol streams (such as compact block forwarding) each has its own specific scenarios. They all take raw bytes as input and use Arbitrary to parse these bytes into a structured test input, which is then executed on the target. Because the input is a generic byte array, we can use AFL++ to fuzz these scenarios, as it provides support for snapshot fuzzing using Nyx.

While developing separate scenarios to test various P2P protocol streams (transaction forwarding, dense block forwarding, chain reassembly, etc.), it suddenly occurred to me that there are advantages to overlapping between them. For example, to test dense block forwarding or chain reassembly, it's not unreasonable to assume that submitting transactions of different shapes and types to the test node simultaneously (as in the transaction forwarding test scenario) would trigger a bug. Therefore, the idea shifted to developing a very broad scenario to test the entire P2P interface of the node, encompassing everything. Fuzzamoto includes a custom LibAFL -based fuzzing engine specifically for this fuzzing scenario, which we will discuss in detail in later chapters of this series.

Initial success

One of the first scenarios I wrote targeted Bitcoin Core's RPCs, specifically combining various related and unrelated results from RPCs in interesting ways. This scenario calls RPCs in an order selected by the fuzzing engine, then parses a portion of the fuzzy input into an RPC input, or selects from a pool of values returned by previous RPCs. For example, if the test calls generatetoaddress , it might later pass the block hash returned by this RPC as input to other RPCs, or remove a hash value from the fuzzy input.

This scenario successfully uncovered a bug in the block index data structure. This bug only occurs when invalidateblock and reconsiderblock RPC are used simultaneously (both can only be used in test mode).

bitcoind: validation.cpp:5392: void ChainstateManager::CheckBlockIndex(): Assertion '(pindex->nStatus & BLOCK_FAILED_MASK) == 0' failed.While this bug isn't a major security concern (it can only be triggered via RPC limited to test mode), it highlights the power of a fully systematic approach: it immediately reveals that it's a bug, not a false positive (i.e., the background process crashes, which should never happen), and snapshot fuzz testing enables efficient state resetting (which would otherwise only be possible through refactoring without snapshots).

The same bug was also discovered by other contributors who refactored the code and wrote fuzz tests for the block indexing code. The PR adding this work to the codebase had been open for a full year before being merged!

Because Fuzzamoto tests operate at the same level as functional tests, we can convert any Fuzzamoto test case into a Bitcoin Core functional test (this is possible as long as the bug is deterministically reproducible). For example, the following functional test reproduces the block index bug:

from test_framework.test_framework import BitcoinTestFrameworkclass CheckBlockIndexBug(BitcoinTestFramework): def set_test_params(self): self.setup_clean_chain = True self.num_nodes = 1 def run_test(self): self.generatetoaddress(self.nodes[0], 1, "2N9hLwkSqr1cPQAPxbrGVUjxyjD11G2e1he"); hashes = self.generatetoaddress(self.nodes[0], 1, "2N9hLwkSqr1cPQAPxbrGVUjxyjD11G2e1he"); self.generatetoaddress(self.nodes[0], 1, "2N2CmnxjBbPTHrawgG2FkTuBLcJtEzA86sF"); res = self.nodes[0].gettxoutsetinfo() self.generatetoaddress(self.nodes[0], 3, "2N9hLwkSqr1cPQAPxbrGVUjxyjD11G2e1he"); self.log.info(self.nodes[0].invalidateblock(res["bestblock"])) self.generatetoaddress(self.nodes[0], 3, "2N9hLwkSqr1cPQAPxbrGVUjxyjD11G2e1he"); self.nodes[0].reconsiderblock(hashes[0]) self.nodes[0].invalidateblock(hashes[0]) self.log.info(self.nodes[0].reconsiderblock(res["bestblock"]))if __name__ == '__main__': CheckBlockIndexBug(__file__).main()In this way, the developers who need to fix this bug don't need to build Fuzzamoto; they can simply use the tools they are familiar with to debug the problem.

For a list of issues that have been identified and made public so far, please see the boast section of this project's readme .

The next article in this series will explore considerations surrounding nondeterminism.