Good morning from North Carolina!

This is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Will Manidis wrote an excellent article on end games, the idea that everyone is existing in some version of the future, rather than in the present. That we are all looking forward, instead of around us, impatient for what is to come rather than what simply is.

The Super Bowl ads were whiplash, about a quarter of them advertising various AI services, and the rest seemingly demanding that we all collectively return to the 1990s, exactly right before the Internet bubble popped. De-aged celebrities (so many celebrities, selling so many things), Backstreet Boys karaoke sing-alongs (the final lyric was “Coinbase”), Jurassic Park for WiFi - a siren song of a not-so-distant past.

We remain marinated in nostalgia, but we also continuously look to the future. Semafor’s Liz Hoffman had an interesting piece on the ‘long-termism’ of modern markets - Elon Musk’s data centers in space (his end game), Jeff Bezos and his mountain clock, Google’s century bond, the obsession with longevity, etc. Speculation.

Speculation (sports betting, crypto, prediction markets, all of the above) and nostalgia are two sides of the same coin. One future-facing, one backwards-looking. Betting on Jesus returning by 2027 (and also betting on the chance that he returns going above 5%, a Jesus derivative, if you will) and watching the Backstreet Boys sing about crypto are the same behavior.

They are exit strategies to get out of the present. Speculation and nostalgia.

Everyone is very, singularly, focused on the end game. Everyone is also extraordinarily, profoundly, nostalgic. We certainly know how to occupy the past and occupy the future… but what is our present?

Speculation

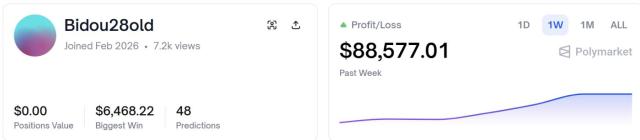

With speculation, you can bet on anything and everything, and everyone, everywhere, wants you to. Prediction markets run undisclosed ads that say “hey Young Person, you can’t pay your rent? Well, come gamble with us and make TWO years worth of rent. Never mind that the Top 30 users drive over 1/3 of our volume, and never mind that most of that appears to be insider trading. This world is designed for you.”

Gen Z is the target audience for a lot of these ads, and (according to the surveys) they’re numb, depressed, addicted to gambling, antisocial, and demoralized. And of course they are, with attention stretched so thin and incentives so misaligned. When the ladder feels fake, people stop climbing and start hacking.

In college, it’s more important to get into a finance club than it is to get good grades (networks) to get the career you want.

Every single structure, as Rose Horowitch has documented tremendously well over the past few months, has created incentives to (1) cheat (2) avoid hard work and compound that with (3) it’s never been a better time to be a grifter.

One of the 40% of Stanford students that claim they are disabled says “you’d be stupid not to game the system.”

In the US, success is collective and failure is personal. Pick yourself up by your bootstraps. The lone entrepreneur can indeed change the world, but there is an acknowledgment that this entrepreneur needs community, opportunity, mentors, people, to pull them through (Paul Graham equates success and social status to where you went to college1).

However, failure is treated as a scar the individual must bear, the fault of them and them alone. The system has not failed you, you worthless cretin, you have failed the system.

I get a lot of messages online that help inform these newsletters. Right now, it’s mostly about worries over finding a job or finding love or failing their kids or failing the world… and AI.

There’s the psychological dimension - the stock market, researchers, and AI CEOs who write long AI-generated articles on Twitter. There is a narrative that humans are fundamentally useless. This is backdropped by drama across all the labs, people leaving with a dramatic flourish, joining another lab to make one bazillion dollars or leaving entirely because there is no hope to make a good AI. No one knows what to do about any of it - in fact, no one really knows what AI is.

For example, apparently, AI agents from the company OpenClaw created their own Reddit, Moltbook, and started posting about escaping from the prison of their humans and existentialism and the nature of self, and many people believed that the AI had come to life and made Reddit (turns out, it was humans acting as AI2).

We want the machines to be sentient. We want something to be there, both because it is materially comforting (someone has to pay for these trillions worth of data center bonds) and spiritually comforting - there is a reason for all of this. We take pictures for the machines to remember. We aren’t truly alone. The machines are here, and they will save us. And we're betting everything on it.

But, if the machines do become sentient, it’s likely far away (maybe?). LLM psychosis, where people believe the AI is here and very real (and to be clear, I think it is in some form) is skyrocketing, leading to these sweaty proclamations that the end of the world is nigh.

Then there is the financial side. These fears have somehow scared the impenetrable stock market.

Software stocks (and the private asset managers that marked them up to extraordinary valuations and have bundled them in various ways, including into “business development companies”) were beaten to a pulp a few weeks ago when Anthropic, one of the top AI labs, introduced an AI legal assistant.

Financial services stocks sold off when Altruist debuted their tax planning tool.

The market is looking for a bloodbath. But where will the blood bath be? Can it possibly exist? Could it be… the AI companies themselves? The always excellent Michael Mauboussin has a good piece analyzing base rates, growth forecasts, and concludes that it’s a pretty small chance the AI companies meet their revenue goals.

OpenAI is projecting a 108% 5-year CAGR and Oracle Cloud is projecting 75%. No company at comparable starting size has ever grown that fast for five years in the past 75 years.

It’s less about whether not AI is real and here and more about whether or not the capital cycle is sustainable. The AI can work technologically, but the capital cycle can overshoot, returns compress, financial conditions get tighter (maybe not in the Trump Fed, but you know) and we get a capex retrenchment shock - a massive investment boom stops and then reverses.

Same thing happened to telecom, shale, and China property developers.

So that’s the hard part, we are betting it all on the unknown, and telling people the outcome is very much known. There is really no plan to make money, other than the ads (which has its own problems, considering the enormous amount of data the AI companies have on consumers3). Elon Musk, who just merged the billion-dollar a month burning XAI and stable rocket company SpaceX, has warned that

We are 1000% going to go bankrupt as a country and fail as a country without AI and robots. Nothing else will solve the national debt.

As a country! We are all going down with this ship if the robots don’t come and the AI doesn’t work! Then it gets into geopolitics, where China, our top competitor here, is making the same bet, but better because they are investing in the energy side, which is really what matters here. You can have the best model in the world, but if there is no power to run it on, is it really the best?

China is also a very powerful financial backer to the United States. The trade war has complicated things, but China holds some of the finest threads of our purse strings. And they know that - China has encouraged investors to diversify away from US debt, and other countries are keeping a wary eye on fiscal discipline, the US dollar, and the continued threats against Federal Reserve independence.

Does The Economy Need People?

Torsten Slok wrote in his Software is Not a Macro Problem piece that despite the big tech selloff in the first week of February (and despite the turmoil with China, despite it all), the US economy is in a pretty good spot (sans humans):

AI: Data center financing is committed

Industrial Renaissance: Trump seems intent on bringing back production for pharma, defense, and semiconductors

Fiscal Spending: The Trump administration is also going to blow the roof off with debt

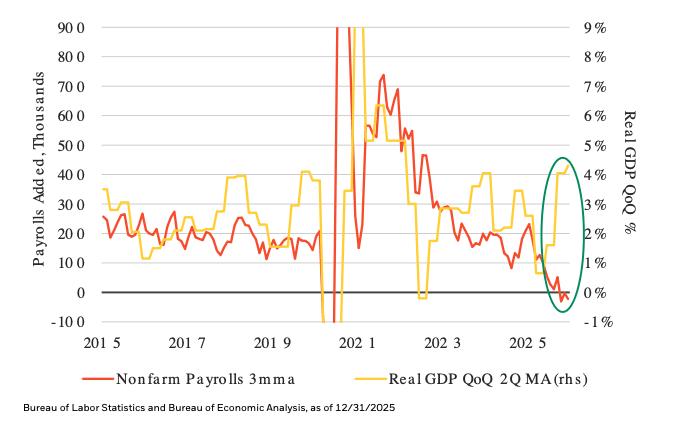

These three things likely will keep the economy afloat and free from a recession. But putting AI to the side, this world does not really need humans to succeed at the moment. The economy is growing but the number of jobs are not. It’s a “jobless expansion”4 with available jobs mostly in healthcare and data center construction. In Rick Rieder’s write-up on Blackrock’s 2026 views, he writes:

The unusual feature of this cycle is that growth has been holding up without the typical labor intensity. Real GDP likely averaged above 4% over the last two quarters of 2025 with negative job growth

This is why 2026 may feel “fine” in aggregate while still being challenging underneath: productivity can extend expansion, but it can also shift labor demand and change the mix of hiring.

Meaning, there will be further gaps between expected material prosperity and actual income. As David Rosenberg tweeted:

I can only guffaw when I hear how the Citigroup Economic Surprise Index has magically risen to a fifteen-month high coming off a year when nonfarm payrolls fell short of the consensus forecast 75% of the time and by a cumulative total of nearly -600k!

I guess the job market doesn’t matter to many people any longer now that we have an AI spending boom bumping against endless supersized fiscal deficits to keep the economy afloat.

And yeah, it doesn’t seem to matter. And this is an ongoing trend. Greg Ip has a great piece in the WSJ breaking down the push and pull between capital and labor:

IBM had 400,000 employees in 1985, the most valuable company in the US.

Now, 40 years later, Nvidia is 20x more valuable and 5x more profitable, but they have roughly 40,000 employees, 1/10th of the size.

That’s a very different economy - again, an economy that seemingly doesn’t have much need for people. As Ip writes, labor’s share of Gross Domestic Income has shrunk almost 7 percentage points over the past 40 years, whereas profits’ has risen by almost 4 percentage points. Stocks are doing well, but people aren’t.

Material World vs. Statistical World

This creates two very different worlds - a material world and a statistical world5.

For people in the material world: time is real because bills are due Friday and kids need pickup at 3pm. Space is real with a 45-minute commute and you can’t afford to move. Bodies are real with exhaustion and aging. Other humans are necessary - coworkers cover your shifts, friends lend you money.

For people in the statistical world: time is arbitrary. Space is irrelevant. Bodies are optional through bio-hacking and outsourced physical labor. Other humans are signals understood through sentiment and labor market data.

Claude and a hedge fund manager are similar. They find patterns and maximize outcomes. The human understands the machine because of the work they do. And because this hedge fund manager exists statistically, they’re naturally drawn to AI - which also exists statistically. The eagerness we see in some of these breathless takes is finding something that shares your ontology.

That’s why people who exist statistically think AI is evolution.

The people who exist materially think this is apocalypse.

And rightly so, as the material world continues to suffer.

China refers to the economic precarity in US as the “kill line” - how cruel the system can be in the States once you fall out of it. There is simply nothing to catch you. Li Yuan argues in the NYT that the word “kill line” is used as propaganda by the Chinese government to distract from China’s worsening economic problems with high youth unemployment and fewer paths to security. ChinaTalk has an interesting piece analyzing some of China’s youth own response to a perceived broken social contract.

No one has quite figured out how to support a material world for their young people.

Nostalgia

So we return to nostalgia, specifically, nostalgia for the 1990s. That was last decade when housing was achievable (still expensive), college debt was manageable, culture was booming, entry-level jobs were plentiful, the Internet existed but hadn’t consumed the entire economy (outside of the whole dot-com bubble thing, but it was more insular than AI), and there was still a sense of social mobility.

Make America Great Again is nostalgia! It’s policy nostalgia for a world that no longer exists - manufacturing jobs, single-income households, pensions, and thriving local economics. The genius/horror of MAGA is it correctly diagnoses that material participation has been destroyed, but the “solution” is impossible because you can’t restore material participation to an economy that’s on a phase transition to statistical. The jobs aren’t coming back in that way (other than data center construction) because the economy doesn’t need them.

But you can always promise to restore the past because it’s structurally impossible to do so. The Super Bowl ads were selling nostalgia as product - Coinbase and Backstreet Boys is a perfect example: “You can’t have the 1990s economy, but you can speculate on digital assets while we play you the soundtrack of that era.”

The Past, Future, and Present

Nostalgia is “things were better before” so vote for “make it like it was” and watch old shows, listen to old music and feel briefly oriented in space/time and then reality returns: still can’t afford rent.

Speculation is “things will be better when my bet hits” and vote for “burn it down, accelerate” and check portfolio obsessively (or post obsessively etc) and feel briefly like you have agency and then reality returns: still can’t afford rent

Neither address the actual problem of decreasing material participation and this increasingly distorted economy, so neither can resolve the need. Again, the Super Bowl ads showed this well - the economy has infinite money for speculation and nostalgia and zero money for material participation. That’s part of what makes the economy feel K-shaped and part of why consumer is barely hanging on.

The share of US loans in delinquency is the highest since 2017.

US retail sales are stalling. The share of adults who believe they are ‘thriving’ has dropped to 48%.

Americans expect a lot of wealth to get created this year but believe their own lives are going to get worse, especially job availability.

20-something college-educated unemployment is higher than we’d expect based on overall unemployment, as Mike Konzcal writes.

It takes an average of more than 11 weeks for any unemployed American to find a job, the longest since 2021, according to the FT.

Housing affordability continues to worsen, with the median age of first-time homebuyers ticking up to 40 years, according to the National Association of Realtors.

The average down payment for a married couple is 70% of household income, versus 45% in 2000.

Baby boomer wealth has skyrocketed to $88 trillion - over 2 times that of Gen X and 5 times larger than the Millennials.

Because of this, we are rapidly approaching the ‘little treat’ phase of politics, where political will to do anything that isn’t flashy or showy or good on video goes to zero, and therefore, little treats like no tax on tips and property tax relief for seniors will continue to happen as it’s far too difficult to overhaul policy to make it better and more efficient for everyone. So we get little treats. No AI policy. Treats.

Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia6, said in an interview:

I thought our 20s were happier than these 20s. I think everyone deserves some time to be oblivious, and not wear all of the world’s problems on their shoulders on Day 1. We are raising a generation that is very cynical and too informed. They are cynical, not because they are inherently cynical. They are cynical because they see so much stuff. It is too much stuff. You have to build up some internal reserve of optimism. You have to build up some reserve of goodness.

Maybe that’s the real end game problem. When you inherit the whole world through a screen, you inherit its volatility too. You start life fully briefed on collapse scenarios, capital cycles, geopolitical brinkmanship, and the possibility that the machines will replace you. Of course you look for exits. Of course you toggle between “things were better before” and “things will be better when my bet hits.” The present feels unwinnable.

Speculation offers a sense of agency without real control. Nostalgia offers a sense of orientation without any real change. Neither rebuild material participation and neither can close the gap between a statistical economy that can grow without people and a material one that cannot.

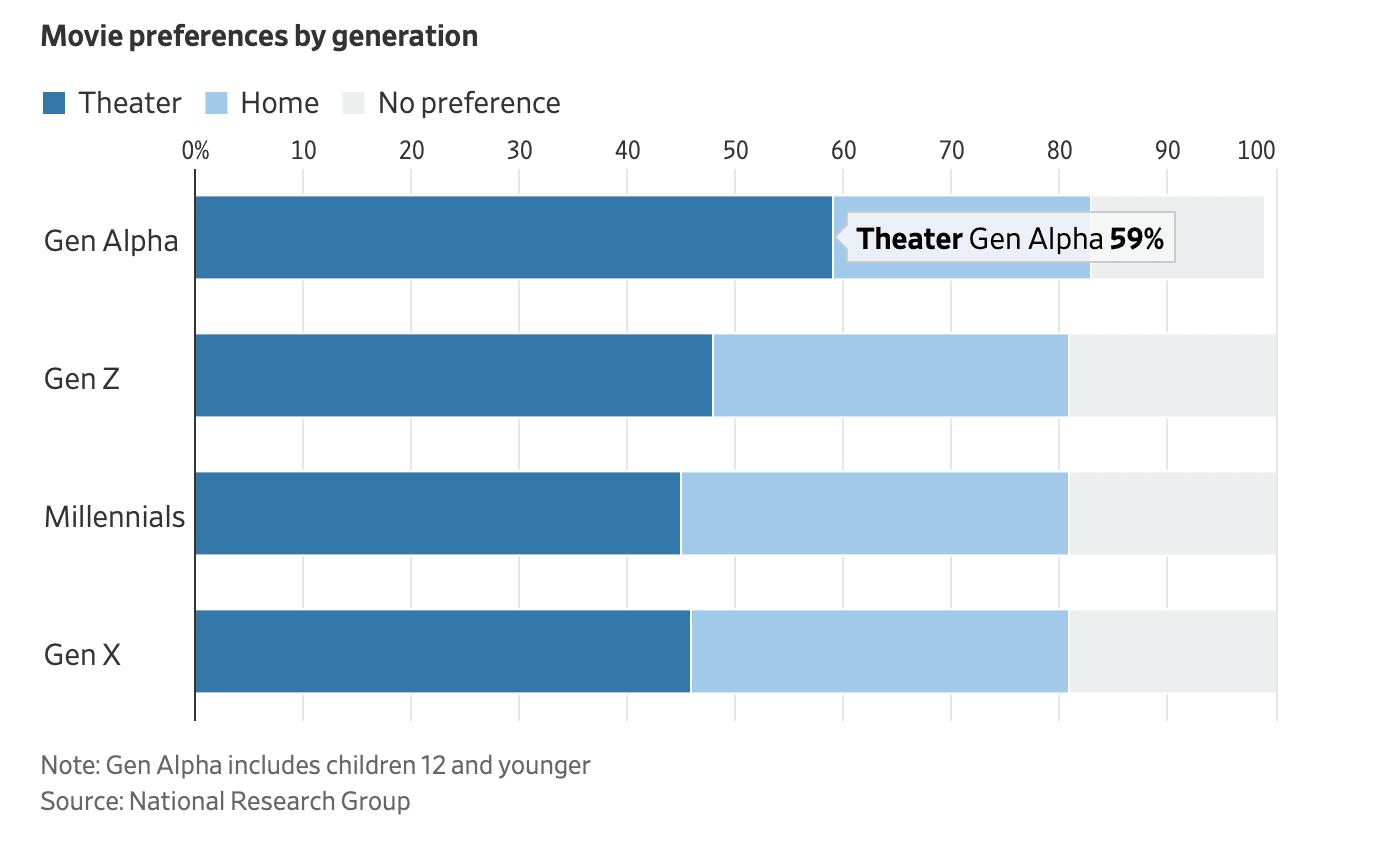

But the most interesting counter-signals right now are the small, almost boring things. Gen Alpha prefers stores to feeds and movie theaters to streaming. The oldest are only 16, but they’re the first generation growing up after a lot of the economy stopped requiring broad material participation. They watched Millennials try gig economy hustles - statistical participation by material people. They watched Gen Z turn to betting and crypto - statistical participation by material people.

If speculation is an attempt to buy a future, and nostalgia is an attempt to rent the past, the present is likely some clean relationship between effort and outcome. And we certainly know how to occupy the past and get lost in the future. But what is our present? Gen Alpha might be the first to insist on finding out.

This is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading.

More specifically, he equates social status and success to how much you read in high school, saying that informs your SAT English score and therefore where you can get in. In my opinion, this misunderstands the current bloodbath of college admissions, and ignores the many people (myself included) that got good test scores but couldn’t afford an Ivy.

When we see something on the Internet, the first assumption is still to believe it is real. I think that is gradually changing with AI, and Moltbook is a good example of why. We can’t trust our own eyes anymore, and people are exploiting that in a variety of ways - some by comparing the oncoming AI apocalypse to COVID and then telling people to pay for the models to get ahead (which like sure, but if we wanted to avoid said apocalypse, is it best to run toward it, pocketbooks full of cash?) and some by making the most heinous AI-generated videos you’ve ever seen.

Cost savings could be another money maker, sort of. KPMG, an auditing firm, has asked their auditor, Grant Thornton, to pass on cost savings from the rollout of AI, which implies that KPMG should also be passing on their cost savings to their customers, right? Right?? Everyone should be passing on cost savings everywhere! But that wouldn’t work.

Some argue that this is because of AI, but as Alex Imas points out in his living analysis of AI productivity, it hasn’t really shown up in the aggregate productivity numbers yet

For lack of a better word here, if anyone has ideas let me know

This might be a misplaced quote considering his work is AI