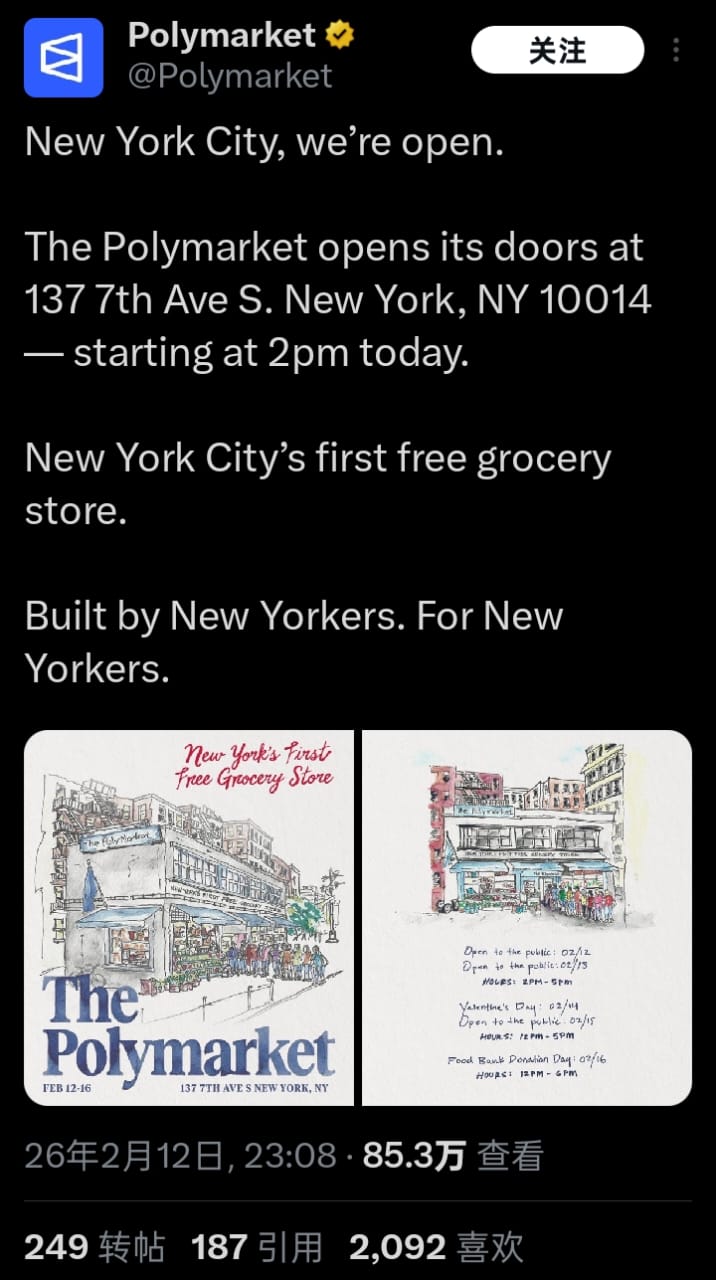

On February 12, 2026, a special store appeared at 137 Seventh Avenue South in New York’s West Village.

The store is called “The Polymarket.” Beneath the sign, a line reads: New York City’s first free grocery store. Built by New Yorkers. For New Yorkers.

Shelves are stocked with tomatoes, eggplants, milk, and bread. There is no cash register. Everything is free. This is the offline retail storefront that Polymarket—a crypto-based prediction platform—spent months planning. Alongside it came a $1 million donation earmarked for New York City’s food bank.

That same week, its competitor Kalshi had just wrapped up a pop-up event: distributing $50 worth of free food vouchers to New Yorkers queuing at the West Side Market. The line snaked for blocks. Nearly 1,800 people signed up.

This is not a year-end charity drive by a nonprofit. It is what two prediction market giants—together valued at over $20 billion—chose to do, on the same street, in the same week, without coordination.

The Strangeness Barrier of Prediction Markets

Prediction markets are, by nature, an industry with a high barrier to entry.

It requires users to understand binary options, settlement oracles, YES/NO share pricing—and to deposit funds into an on-chain contract to bet on whether the Fed will raise rates, who will win the presidential election, or whether a video game will launch on schedule. Even after Polymarket processed over $44 billion in trading volume in 2025, reached a valuation of $9 billion, and secured a $2 billion investment from ICE (the parent company of the NYSE), its total user base remains below 920,000.

920,000 users is roughly the follower count of a top crypto influencer on X. But for a platform aiming to become the global infrastructure for prediction markets, that number is far from enough.

Where are the real incremental users? Not on Wall Street—they already have Bloomberg terminals. Not in crypto circles—that’s already a red ocean. The real incremental user is the New Yorker lining up outside a supermarket for free eggs. They may never have heard of decentralized prediction protocols, but they know $50 worth of beef will feed them for two days.

When an industry has yet to be understood by the public, a brand’s greatest enemy is not its competitors, but strangeness. And the most effective way to eliminate strangeness is not to flood social media with ads—it is to let someone touch you. The New Yorker who picks up free milk won’t become a prediction market trader overnight. But the next time they see the word “Polymarket” in the news, what comes to mind will not be a distant crypto casino, but that store on Seventh Avenue where they once picked up tomatoes.

II. Two Divergent Paths: Physical Store vs. Pop-Up

The recent moves by Polymarket and Kalshi reveal two fundamentally different strategic choices.

Kalshi’s approach is classic pop-up thinking: rent supermarket space, hang prediction-themed banners, hire part-time staff in green hoodies to hand out stickers that say “Kalshi loves free markets.” The event lasted three hours. This is the kind of viral marketing Silicon Valley tech companies excel at—high-efficiency, low-cost, easily replicable.

Polymarket chose a different path entirely. Instead of borrowing an existing venue, it leased a storefront, secured permits, spent months preparing, and opened a real, operational physical store. Its official announcement emphasized: this is not a temporary pop-up stall—it is a dedicated retail space built from scratch over several months.

Kalshi is competing for event buzz. Polymarket is competing for cognitive assets. A pop-up ends in three hours. The crowd disperses. The stickers end up in a drawer. But a store stays open. A permanent Polymarket sign appears on a street corner. A $1 million donation enters the New York City Food Bank’s annual ledger—and will be cited in every future charity report.

This is a shift in competitive focus: from on-chain metrics to street-level narrative. When regulators and the public come to scrutinize the prediction market industry in the future, a donation receipt stamped by a city food bank will carry more weight than any trading volume chart.

III. From Boardrooms to Supermarket Entrances: The Regulatory Chessboard

No conversation about prediction markets can avoid regulation.

In 2022, Polymarket was fined $1.4 million by the CFTC and subsequently blocked U.S. IP addresses, effectively exiting its home market. It wasn’t until 2025, after receiving CFTC approval, that it began to gradually re-enter the United States.

But federal approval does not guarantee state-level clearance. New York State legislators are currently reviewing the ORACLE Act, which proposes strict restrictions on event-based prediction markets—or even a direct ban on certain types of bets by New York residents. Another bill would require prediction market operators to obtain a state license before doing business.

Legislators’ core concerns: insider trading, market manipulation, and everyday users mistaking prediction markets for gambling without fully understanding the risks.

In the past, the industry’s response to regulatory pressure was to hire lobbyists, submit legal briefs, and explain technical principles at congressional hearings. These efforts are necessary—but they only work inside regulators’ boardrooms.

Polymarket’s latest move extends the battlefield from the boardroom to the supermarket entrance. Months from now, when New York legislators debate whether to pass the ORACLE Act, a letter from a constituent may appear on their desks: Polymarket donated food to our community during a harsh winter. Their store is on Seventh Avenue. There were no frauds, no scams.

New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani once proposed opening public grocery stores across the city’s five boroughs to lower food prices. Polymarket’s free grocery store sits neatly within that policy narrative. It did not coordinate with City Hall—nor did it need to. When a tech company’s actions resonate with the stated priorities of elected representatives, public sentiment tilts accordingly.

IV. Trust: The Most Expensive Compliance Cost in Prediction Markets

Back to the original question: why is a prediction market platform handing out free groceries?

Strip away the charitable packaging, the brand marketing, the PR messaging. Beneath it all, the logic is simple: ordinary people are afraid to deposit money into a website they don’t understand.

Crypto wallets, private key management, on-chain gas fees, order book depth—these are real cognitive costs for a New Yorker working ten-hour shifts. The higher the cognitive cost, the higher the trust barrier. The higher the trust barrier, the more expensive customer acquisition becomes.

And offline grassroots promotion is the oldest, dumbest, and most proven method in human commercial history for overcoming trust barriers.

Chinese internet companies validated this playbook a decade ago: download our app, get a bag of rice. Register an account, take home a tray of eggs. Western tech elites once dismissed this as crude, unscalable, beneath the dignity of Silicon Valley branding. Yet here we are, ten years later: New Yorkers braving the cold to queue for $50 food vouchers—the same queues, the same commercial logic, that snaked outside community supermarkets in China years ago.

Blockchain or AI. Prediction markets or DeFi. Every consumer-facing tech product eventually arrives at the same question: How do you get someone who has never heard of you to trust you?

Polymarket’s answer is a free grocery store on Seventh Avenue. The tomatoes and eggplants on its shelves are the most expensive customer acquisition cost this industry has ever paid—and the security deposit it must put down as it attempts the journey from niche cypherpunk circles to mainstream adoption.

On February 12, The Polymarket opened its doors. That day, New York’s temperature hovered around freezing.

Many questions remain about this store. How long will it operate? Will it face the same inventory and rent pressures as any ordinary retailer? Of the New Yorkers who walked out with free groceries, how many will eventually become active users on the platform?

These questions matter. But at this moment, they may not be the ones Polymarket is most focused on.

What it really cares about is something else: when the prediction market industry one day needs to defend itself, can it produce something more compelling than “our technology is very advanced”?

A $1 million donation receipt from the New York City Food Bank. A storefront sign on Seventh Avenue. The memories of thousands of New Yorkers who once picked up free milk.

These are the chips Polymarket is quietly stacking.

Whether those chips can be redeemed—for regulatory forbearance, for public trust—no one can say for sure. But at least this much is clear: this company understands that in the game of financial innovation, compliance is not a legal question. It is a trust question. And trust is never earned in an office.