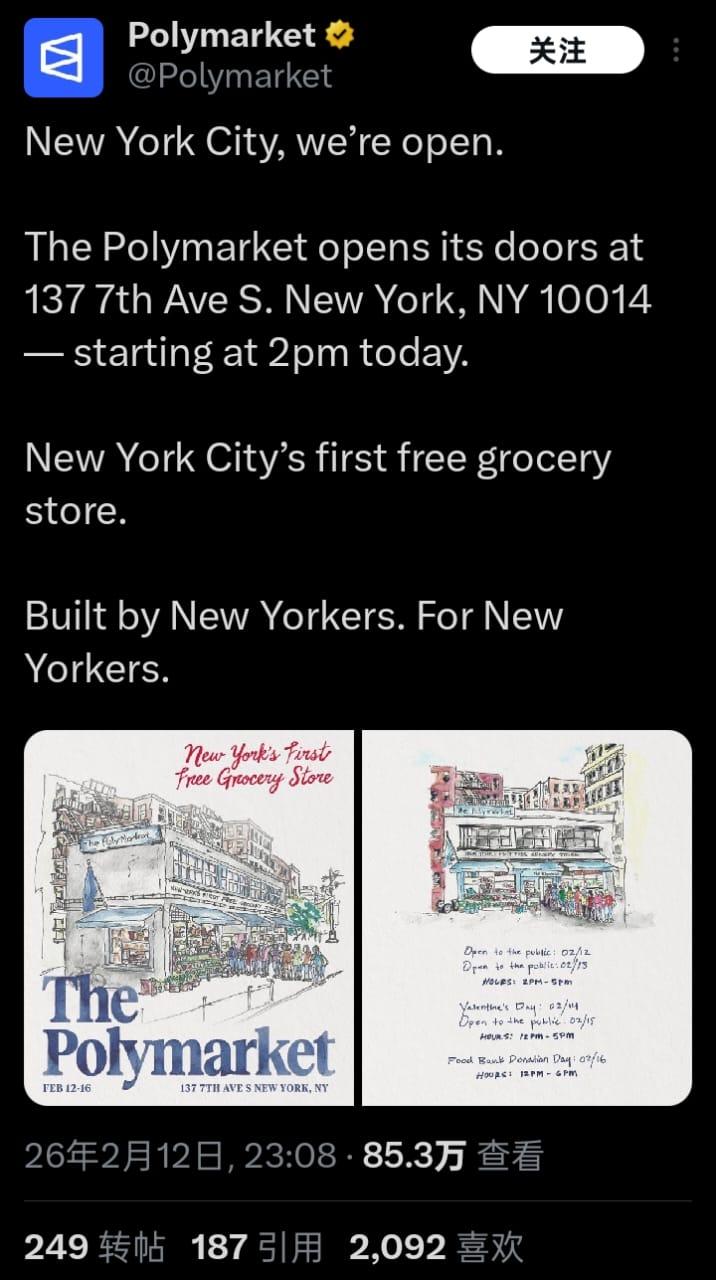

On February 12, 2026, a special shop appeared at 137 South 7th Avenue in New York's West Village.

The store is called "The Polymarket," and below the sign is the text: New York City's first free grocery store. Built by New Yorkers. For New Yorkers.

The shelves are stocked with tomatoes, eggplants, milk, and bread; there's no cashier, and all items are free. This is the physical store that Polymarket, a cryptocurrency prediction platform, has been planning for months, and it comes with a $1 million donation specifically earmarked for the New York City Food Bank.

On the same day, its competitor Kalshi had just finished a pop-up event: distributing $50 free food vouchers to people lining up at the West Side Market, with the line stretching for several blocks and nearly 1,800 people signing up to receive them.

This wasn't a charity's year-end greeting; it was something two prediction market giants, with a combined valuation of over $20 billion, did simultaneously on the same street and within the same week.

Source: X Twitter_Polymarket

I. The Dilemma of Unfamiliarity in Market Forecasting

Prediction markets are an industry with inherently high barriers to entry.

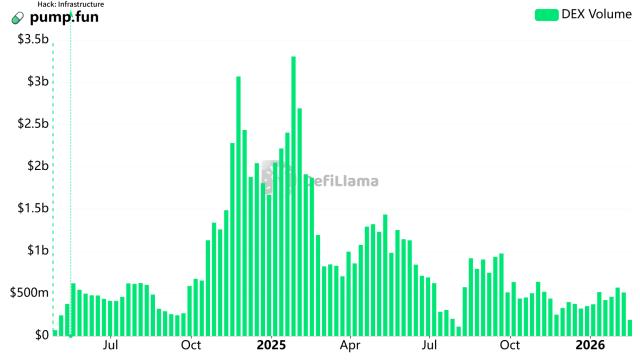

It requires users to understand a series of concepts such as binary options, settlement oracles, and YES/NO share pricing, and to deposit funds into an on-chain contract before placing bets on events such as whether the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates, the results of the presidential election, or whether a game will be released on schedule. Even if Polymarket achieves a trading volume of over $44 billion, a valuation of $9 billion, and receives a $2 billion investment from Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), the parent company of the NYSE, in 2025, its total number of users will still be less than 920,000.

920,000 is the number of followers a top cryptocurrency blogger has on Twitter, but for a platform aiming to become the global prediction market infrastructure, that number is far from enough.

Where are the real incremental users? Not on Wall Street, where Bloomberg Terminal already exists. Not in the crypto community, where it's already a red ocean. The real incremental users are that New Yorker queuing outside the supermarket for eggs. He may have never heard of decentralized prediction protocols, but he knows that $50 worth of beef is enough for him for two days.

When an industry is not yet understood by the public, a brand's greatest enemy is not competitors, but unfamiliarity. The most effective way to eliminate unfamiliarity is not to run more ads on social media, but to let someone truly connect with you. A citizen who received free milk won't immediately become a prediction market trader, but the next time he sees the word "Polymarket" in the news, what comes to mind won't be some far-off crypto casino, but the store where he received his tomato.

II. The Divergence Between Brick-and-Mortar Stores and Pop-Up Stores

The clash between Polymarket and Kalshi reveals two drastically different strategic choices.

Kalshi's strategy was a classic example of flash marketing: renting a shopping mall venue, hanging banners with the predicted theme, and hiring part-time workers in green hoodies to distribute stickers that read "Kalshi loves free markets." The event lasted only three hours. This is a common viral marketing tactic used by Silicon Valley tech companies—efficient, low-cost, and easy to replicate.

Polymarket, however, took a completely different approach. Instead of using any existing space, it leased a store, obtained permits, and spent months preparing to open a truly physical store. The official announcement specifically emphasized that this was not a temporary pop-up booth, but a dedicated retail space planned and built from scratch over several months.

Kalshi is vying for the buzz of the event, while Polymarket is vying for cognitive assets. The pop-up event will end in three hours, the crowd will disperse, and the stickers will be tossed into drawers. But one store will continue to operate, a permanent Polymarket sign will appear on a street corner, the $1 million donation will go into the annual accounts of the New York City Food Bank, and will be mentioned in every future charitable report.

This represents a shift in the competitive dimension from on-chain metrics to street-level narratives. When regulators and public opinion examine the prediction market industry in the future, a donation receipt bearing the seal of a city food bank will be more persuasive than any transaction volume data.

III. The Regulatory Game Extending from the Conference Room to the Supermarket Entrance

When discussing prediction markets, regulation is an unavoidable topic.

In 2022, Polymarket was fined $1.4 million by the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and subsequently had its U.S. IP address blocked, effectively withdrawing from the domestic market. It didn't begin its gradual return to the U.S. until it received approval from the CFTC in 2025.

However, federal approval does not guarantee smooth sailing at the state level. New York lawmakers are considering the ORACLE Act, which plans to impose strict restrictions on event-based prediction markets, and even outright ban New York residents from participating in certain types of betting. Another piece of legislation would require prediction market operators to obtain a license from the state government to operate.

Legislators’ core concerns are insider trading, market manipulation, and ordinary users equating market prediction with gambling without fully understanding the risks.

In the past, prediction market platforms dealt with regulation by hiring lobbying firms, submitting legal opinions, and explaining their technical principles at congressional hearings. This work was certainly necessary, but it only worked in the meeting rooms of regulatory agencies.

Polymarket's actions this time extended the battleground from the meeting room to the supermarket entrance. Months later, when New York State legislators were debating whether to pass the ORACLE Act, a letter from a resident of the district might appear on their desk: Polymarket has donated food to our community during the winter, their store is on Seventh Avenue, and there has never been any fraud or scam there.

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani campaigned on a platform of opening public grocery stores in all five boroughs to lower food prices. Polymarket's free grocery store simply falls within this extended policy narrative. It wasn't coordinated with the city government, nor did it need to. When a tech company's action resonates with the claims of elected officials, public opinion naturally tilts in one direction.

IV. Trust is the most expensive compliance cost in predicting the market.

Going back to the initial question: Why would a prediction market platform distribute eggs offline?

If you break down all of Polymarket and Kalshi's actions, removing the charity packaging, brand marketing, and public relations rhetoric, the underlying logic is actually very simple: ordinary people dare not deposit money on a website they don't understand.

Crypto wallets, private key management, on-chain gas fees, order book depth—these concepts represent a real learning curve for New York City workers who toil ten hours a day. The higher the learning curve, the higher the trust threshold. The higher the trust threshold, the more expensive customer acquisition becomes.

Offline promotion is the simplest yet most effective way to overcome the trust barrier, a method that has been repeatedly proven in the history of human commerce.

Chinese internet companies validated this methodology a decade ago: offer a bag of rice for downloading an app, a carton of eggs for registering an account. Western tech elites once scoffed at this, deeming it a crude, unscalable promotional tactic unbecoming of Silicon Valley's brand image. But today, ten years later, videos of New Yorkers queuing in the cold for $50 food stamps are essentially no different in business logic from the long lines outside Chinese community supermarkets back then.

Whether it's blockchain or artificial intelligence, prediction markets or decentralized finance, all technology products aimed at mass consumers will ultimately arrive at the same question: How do you get someone who has never heard of you to entrust their trust to you?

Polymarket's answer is a free grocery store on Seventh Avenue. The tomatoes and eggplants on the shelves represent the industry's most expensive customer acquisition cost to date, and also the trust deposit the industry has to pay as it tries to move from niche geeks to mainstream applications.

The Polymarket opened for business on February 12. The temperature in New York City that day was around zero degrees Celsius.

The fate of this store remains uncertain. How long will it operate? Will it face inventory and rent pressures like a regular retail store? How many of those who received the free food will ultimately become actual users on the platform?

These are important questions, but at this point in time, they may not be Polymarket's primary concern.

What it really cares about is something else: when the prediction market industry needs to defend itself someday in the future, can it produce evidence that is more compelling than "our technology is advanced"?

A $1 million donation receipt from the New York City Food Bank, a sign on Seventh Avenue, and the memories of thousands of citizens who received free milk—these are the assets Polymarket is currently building.

Whether these leveraged assets can translate into regulatory tolerance and public trust at crucial moments remains uncertain. However, this company has at least realized that in the game of financial innovation, compliance is not a legal issue, but a matter of trust. And trust is never earned in the office.