By Kyle Chayka, Staff Writer, The New Yorker

Original Compilation: Perry Wang

This article is from WhoKnows DAO.

WhoKnows Guide:

The meme economy is also the history of the personal experience of capitalism in the 21st century: it is about identifying the right scarce digital meme at the right time.

Note, the title is just for traffic, not any investment advice. Originally published in January 2021.

I'm writing this long post at full throttle because it's been a complete simmer in my head for the past week, with all sorts of ridiculous ideas popping up. If you want a coherent account of GameStop, Reddit, Robinhood , and stock manipulation, read this article by Taylor Lorenz in the New York Times. In the meantime, I'll dissect the subject with a slightly different approach: anecdotally, abstractly, invested with resentment for the 21st-century economy we've unfortunately experienced.

#meme economy

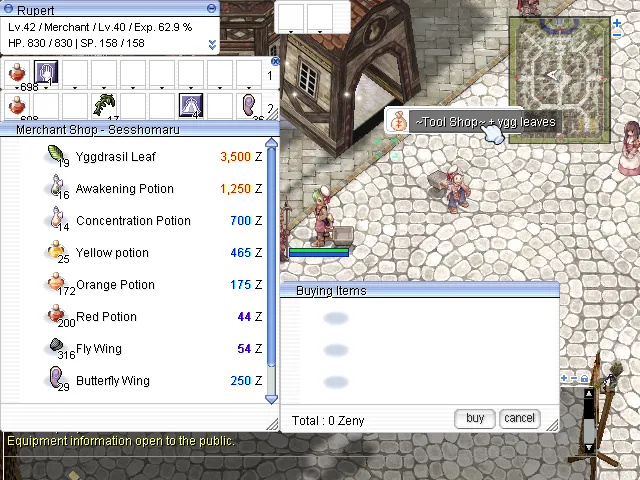

During my freshman year of high school, I was obsessed with an online role-playing game (MMORPG for nerds) called Ragnarok Online. Like all other games of this genre, it has a variety of characters for you to choose from and play with millions of other players: knight, wizard, thief, archer, priest. There are also merchants.

Every MMORPG is also a kind of digital marketplace where various goods are traded: players earn in-game currency and spend it on in-game purchases, mostly things like weapons, potions or special armor. You fight monsters, drop loot, and sell it to the in-game automated (NPC) shop for currency that you can use to buy new gear. never ending.

The whole game is pretty much on this principle: slow growth of digital currency and more and more expensive items.

But the merchant's role in the game is not just to fight monsters, but to arbitrage when exchanging items. If you are a businessman, you can sell loot to NPC shops at a higher price and buy items at a cheaper price. Crucially, you can open a shop. Through the bubble dialog that pops up on your avatar, Sell directly to players at a price you decide.

Assuming you're in a town in the game, you can buy a dagger from the in-game store for 20% off its regular price. The money making strategy is to set up your own shop outside of the real one, sell the daggers for less than the normal price, say, 50% off, and then pocket the difference. Of course, this is money-making by volume: you have to sell dozens of daggers at a time to make a lot of money, so enough capital is needed to buy stock from stores to make a small profit, which you can then reinvest in more daggers. on many items.

That's what I did! To me, it's more fun than killing giant monsters or anything else in the game. Often, you'll see hordes of merchants in front of shops, and they may offer different items, or undercut each other's prices until one player gets up and walks out - and then the remaining merchants can raise their prices, and up again profit margin.

This cycle was probably the first lesson I learned about the involution of post-industrial capitalism, which I will have to deal with for the rest of my life: we compete not only on supply and demand, but even in a virtual economy. Such introversion, the objects in the virtual economy are completely man-made, just pixels and calculated drop rates, which can be adjusted by the game company at will. The economy is arbitrary, and any set of pixels is better than another set of pixels.

For example: there will be monsters in Santa hats during the holidays, you kill the monsters, get Santa hats, put them on your avatar, but after the week of Christmas, they are canceled, the object of your dreams Disappeared until a full year later, you can repeat the process.

There's also a lot of cheating: I sometimes use external bots to manipulate my character, idling to level up while I'm sleeping. I don't really want to cheat because we players just do it for fun. In the 2000s, there was no actual connection between dollars and in-game virtual goods; you were rewarded, it was just an honor to have something to show off in the game, it was your time in Ragnarok. Glory or influence in a career.

Unfortunately, I didn't absorb this casual digital capitalism lesson well, or I might be rich by now.

I took my first economics class in college, calculating supply curves, tariffs, import and export balances, currency exchange rates. This seemed important to me as an international relations major at the time. When I graduated, I tried to find a job that would pay me an annual salary, understanding that this is how a person makes a living, receiving a pay check every two weeks from an entity called a corporation. Of course, in the real world in 2010, right after the financial crisis, I first got an internship with a modest stipend, and then I got informally paid. As of now, I have worked for myself for ten years. There was never such a thing as a salary.

Now I realize that Ragnarok has taught me everything I need to know about money and profit in our time, a lesson more important than almost anything else in my life. Here’s the lesson: Santa’s hat is everything, digital scarcity is often more important than physical scarcity, capital in your hands is almost always better than hard work: be a businessman, not a worker.

As an adult working in the economy, my career has been made up of a series of shocks, or negative epiphanies. My parents lived on engineers' and teachers' salaries; not that they didn't own stocks or participate in the stock market, but I thought: I didn't understand the concept of equity in capital or means of production until - like many things , I have fully felt its enormous impact in my own life.

Since I've written about art topics at the beginning of my career, probably the first thing I noticed was skyrocketing prices for young artists whose work was exhibited in certain galleries, or received proper attention, probably just Meaning that the work they once sold for $1,000, or were even given away for free, is suddenly worth $100,000.

(I was interviewing for a gallery internship once, and a Rothko painting was leaning casually next to the chair I was sitting in). Another time I visited the country house of a friend’s art dealer friend who worked for a wealthy family; they took a small Roman statuette off the wall and tossed it around. The close relationship between the art world and money does not mean that you can definitely make money in it; in the art circle, some people can earn a lot of money and can afford luxury items that have no function at auction, while others of people desperately need money to continue their artistic career.

The next shock was the reemergence of Silicon Valley in the 2010s as the engine of enormous fortunes my age (or younger). An early employee at a tech company, who might just be a developer with a normal social life, amasses a small stake in the business and gets rich as the business soars into the billions. Because these companies have replaced filters in some of the previous massive capital flows — Google, for example, has a monopoly on advertising. These tech companies go public or get bought, and the small stakes owned by the above-mentioned employees are worth millions: employees get rich instantly, not because of their salaries, or the importance of their work, but because they participated in the cannibalization The software blast furnace of the world. With the sale of Tumblr to Yahoo for $1.1 billion in 2013 (a deal that was too funny), one Tumblr employee who joined early enough, even on the editorial side, made tens of dollars from the company's stock Ten thousand U.S. dollars. A small amount of money for a tech business, but never in my life have I seen so much money, neither have my parents and grandparents.

# Cryptocurrencies and the GameStop Shock

Cryptocurrencies can be called my third shock. Currencies like ethereum ( ETH ) and bitcoin ( BTC ) are arcane equations that take up enormous server resources to maintain unbreakable levels of digital scarcity: like Santa hats in Ragnarok, they actually It's gold and can't be canceled after the holidays, but there are only 1,000 of them, and you can trade hat pieces.

As a journalist, I've seen these capital mutations emerge and become worth a few dollars. very interesting! A strange experiment with digital currencies, and then their prices increased exponentially. Cryptocurrencies that sold for a few dollars in the early 2010s are now worth tens, then hundreds of thousands of dollars. Man who used to buy LSD on the dark web became a millionaire.

I imagine it's the same feeling people felt when Gutenberg started printing Bibles in the 15th century: from nothing, what we once considered sacred was produced seemingly infinitely, and the world was never the same. It breaks some unspoken rules of the social framework.

I don't regret not buying BTC or other cryptocurrencies sooner because I can't understand what this money means to me. I don't have any major problems in my life and no shortage of major opportunities that money can fix. I can't afford to buy my own real estate in a major US city, but by the standards of our time, I'm perfectly fine. And yet, with those magic numbers pouring into certain accounts, I know some people who have become secret stewards of shadowy venture funds, and if they choose not to work, they won't have to work another day for the rest of their lives. I think that's what money really does change for me: a sense of security about the future, which is more of a threat than an opportunity right now. If you buy BTC, then you can afford water rights in 2050, or get a COVID-19 vaccine without waiting in line.

The same thing happened again last week: A small group of stock traders on Reddit, carefully researched and acting on the bets of at least a few major hedge funds, pushed outdated video game retailer GameStop "Twilight" was also prevalent in the early 2000s), and its stock price soared to 10 times, 20 times its previous price a few weeks ago. Hedge funds shorting the stock had to buy it when it rose. This is an era where young people rise up against corporate overlords, but there are still some little guys who make their fortunes in it.

If I somehow knew these clues, would I invest $10,000 long GameStop stock? Can I get out in due time? $200,000 in profit, more than four years of my income.

The point where money still hits me hard is this: it's a lot of little money. Airbnb co- founder Brian Chesky's personal net worth soared into the billions when his company IPOed. Just as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos profited handsomely from the paralysis of civilization caused by the quarantine. These people may never run out of money to spend - you could call it rich, just like the pharaohs, even if they spend a lot of money like space travel, it still can't slow down their wealth growth. In the face of such vast inequalities, the paycheck, the family's health insurance policy, or the accruals for a cup of coffee, all become insignificant.

I'm not trying to discredit anyone's work; I know that noticing the right opportunity, seizing it, and being a survivor until it can finally be cashed in takes as much skill and awareness as luck. You still have to pay taxes, unless you also figure out a tax avoidance route, of which there are many in the US. Not that I think what I've been doing for the last ten years is worthless, sitting at my laptop, noticing certain things, writing about them, collecting data points of my personal worldview and trying to share it with other people -- This kind of work necessarily requires a certain degree of narcissism. I could have chosen to become a private equity banker, or move to San Francisco to participate in the startup lottery; I could have made investments based on my hunches instead of publishing them for public consumption.

But I'm describing these phenomena now just to organize my thoughts around them, to show you that the world and normal life have moved away from the small-scale expectations I grew up with, from the vague promise society made: a meritocratic education , the value of pursuing happiness, the value of hard work, and so on. As we are forced to live like medieval peasants under the rule of a psychotic king, I am trying to digest the lessons capital has taught me so that I can better gauge future momentum. For what purpose, I'm not sure - knowing when might give me a headache so I can avoid it? Or try to take your chances? Sometimes I think, I have no other choice. This dilemma feels like you own a tiny amount of Amazon and Palantir and get a small profit while being exploited by the giants, or you're just purely screwed.

When we look at what's going on in the digital capitalist economy, think that wealth somehow means a measure of success; that the recipients of wealth are totally deserving; The pain of adequate support is inevitable; how long can this illusion last? I grew up thinking that labor is worth it, that it has a steady value. Maybe it is, but the fact is that the non-labor value of capital is much higher, the latter being like the tides, and the former being little more than a few splashes on the beach. Yet I also think that, if meaning has any value, it means much less.

# lucky roulette

The French economist Thomas Piketty published a book in 2014 called Capital in the 21st Century that sums up our problem with a theory: R > G. The rate of return on capital (profits or dividends from companies; rents on real estate, etc.; interest) is already greater than economic growth rates, overall social output, or labor compensation. It's easy to explain: a GameStop retail clerk bought $GME stock with his salary a month ago, and he/she will make many times more money from the stock than his/her monthly salary, even though they That's why the company exists.

Of course, it's a lucky roulette wheel, and you'll need a lot of upfront capital to buy enough stock to profit from the stock's rise. But it really is pure R > G: the fundamental value of the labor to run the store, and even the physical infrastructure on which the store operates, is a drop in the bucket against the random trends of the stock. Trends themselves are artificial. The rationale for GameStop's stock rise wasn't the belief that GameStop might be worth more money because of a dramatic improvement in operations; The stock price was knocked back to where it was in 2020, the creator of the joke grew rich from the drama, and all the money invested by subsequent followers was wasted.

This is a meme economy that is ultimately settled in real dollars, not just vague social media influence.

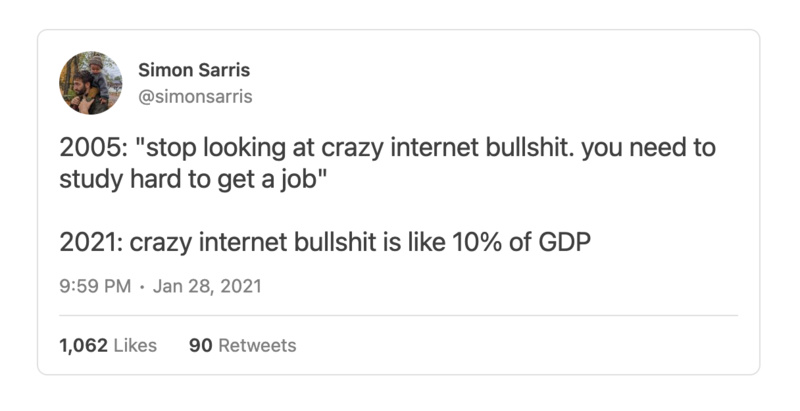

GameStop clearly demonstrates the Ragnarok Santa hat theory of digital capitalism. Making money isn't from a paycheck to a job, or even slow index fund returns, but from discerning the right scarcity number meme at the right time, knowing when to grab the Santa hat before it's gone. Guessing the right meme pays off as much as the best venture capital investment or being an early Apple employee. You need capital to play the game, but it's much lower than being an accredited investor in the US, which requires an annual income of more than $200,000 or a net worth of $1 million. Beyond that, all the meme economy needed was time, snooping, and good judgment developed through insane amounts of time online — Internet addiction was an embarrassment when I was a kid, and probably still is Mental dysfunction.

For me, Bitcoin, GameStop, or working for Facebook , it's like every Christmas hat I've collected suddenly sells for a whopping $100,000. It's as if you got rich overnight just because you knew which episode of Great British Bakeoff was actually the best. Forgive me, but what is this? (That’s already the case in the art world, but you have to meet the right people in the real world and pass the right tests to get into the money game.)

The earning power of capital far exceeds that of labor, and the soaring capital gains in the Internet age, its replication rate keeps hitting crazy peaks, and it has more to do with entertainment, meme and fandom than with income, productivity or utility.

If my high school teachers knew this reality, they would have sent me home to the basement to play video games. I used to think that stability was shaped by career advancement, slow payoffs at work, respect from peers, and establishing authority in a field, even if not through paid full-time employment. However, my notion of professional development has been superseded by a series of increasingly arcane gambles in our lives and digital platforms. Any successful bet could pay off more than years of work.

We want to onboard the right startup, buy the right cryptocurrency, be an early adopter of a new platform before the audience floods in, and become our own meme. This is how the meme economy works: you spread the word, you get attention, you get sponsorships, you sell memberships, you get books.

Satisfaction with work sometimes seems to succumb to the invisibility capital wants (because it is more efficient to be unnoticed), like forgetting that there is a behind-the-scenes game. Or believe that there is a more solid foundation or logic to all of this than Santa hat-shaped pixels appearing and disappearing. And that Christmas hat is up for grabs by millions of players in the virtual world.

Usually the end of an article will put forward some suggestions for solutions, or give an outlook on the future of a problem or an industry, in order to leave some hope for readers and give a clear description of this otherwise indescribable world.

But this article is not a traditional publication. I think we are in a chaotic world, and we are still trying to summarize the rules of this era of accelerated development. In 2014, the US government told us that companies are people too. In order to survive or benefit from the ever-evolving structures of digital capitalism, people must do the opposite and become companies, marketplaces, platforms, or memes. Because only those things can thrive.