Author: Joseph Politano

Original compilation: Block unicorn

Will the Fed Lend $300 Billion in Emergency Funding to Banks After Silicon Valley Bank Failed?

For the first time since 2020, the Federal Reserve provided emergency support to the US banking system. Several major regional banks are struggling after last week's collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank , whose distressed assets are still managed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The Federal Reserve has pledged to protect banks and the financial system throughout the crisis and has backed up those commitments with strong practical action -- supporting the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which opened up a new bank lending facility over the weekend, easing emergency bank lending. The terms of the credit line and the commitment to provide liquidity to any distressed thrift institution.

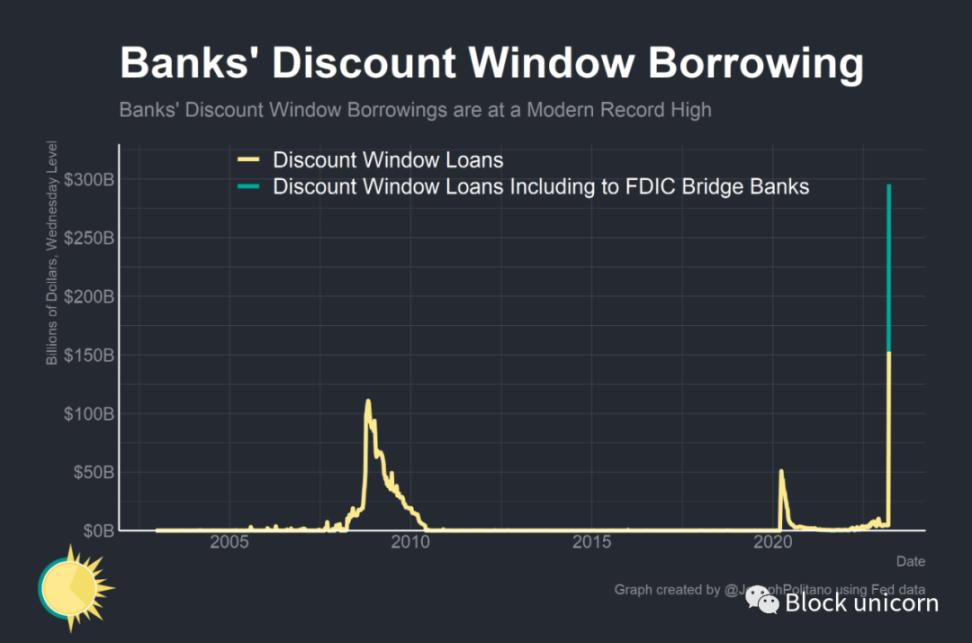

They also provided more than $300 billion in new loans to U.S. banks as of Wednesday, more than double the amount of direct credit created at the height of the pandemic in early 2020. That has effectively contained the crisis so far — there have been no more bank failures in a week since the FDIC, Fed and Treasury joined forces to tackle the crisis — but many banking institutions remain at risk. So, will the Fed's $300 billion emergency response - and the slew of new policies they have enacted - be enough to prevent a crisis?

Breaking Down the Fed's Emergency Lending

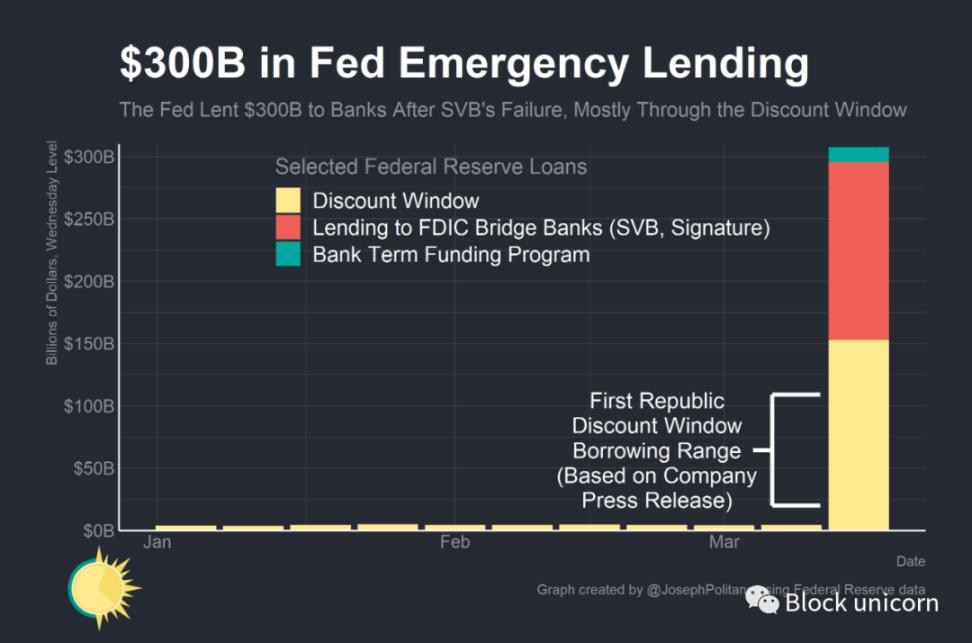

As of Wednesday, the Fed had provided more than $300 billion in secured direct loans to the banking system -- more than at any time since the global financial crisis -- to stem the fallout from the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank. More than $11.9 billion in loans came from the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), a newly created facility that allows banks to pledge government-backed securities at face value in exchange for loans for up to one year.

However, most of the Fed's lending ($295 billion) comes from the discount window, a collateralized direct lending facility that the Fed has historically maintained to provide emergency liquidity to banks. The Fed provided $142 billion in loans to bridge banks under the FDIC for SVB and Signature Bank , and $152 billion in loans to private banks through the discount window. Of that $150 billion in private borrowing, one private bank probably accounts for the majority - First Republic Bank, which has issued a statement saying their discount window borrowing has grown from $20 billion since Silicon Valley Bank collapsed. US$ to US$109 billion.

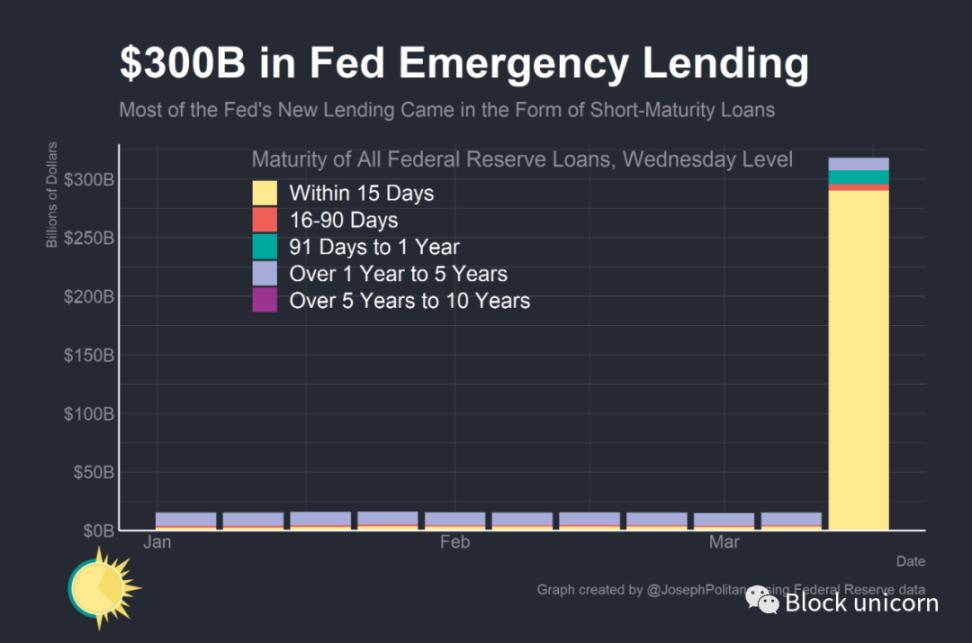

The vast majority of these emergency loans were very short-term loans, with $290 billion of loans maturing within 15 days, a record high, and only $540 million of loans maturing between 16 and 90 days, almost all Discount window loans. In addition, $11.9 billion in loans matured between 3 months and 1 year, corresponding almost exactly to BTFP's loan maturity.

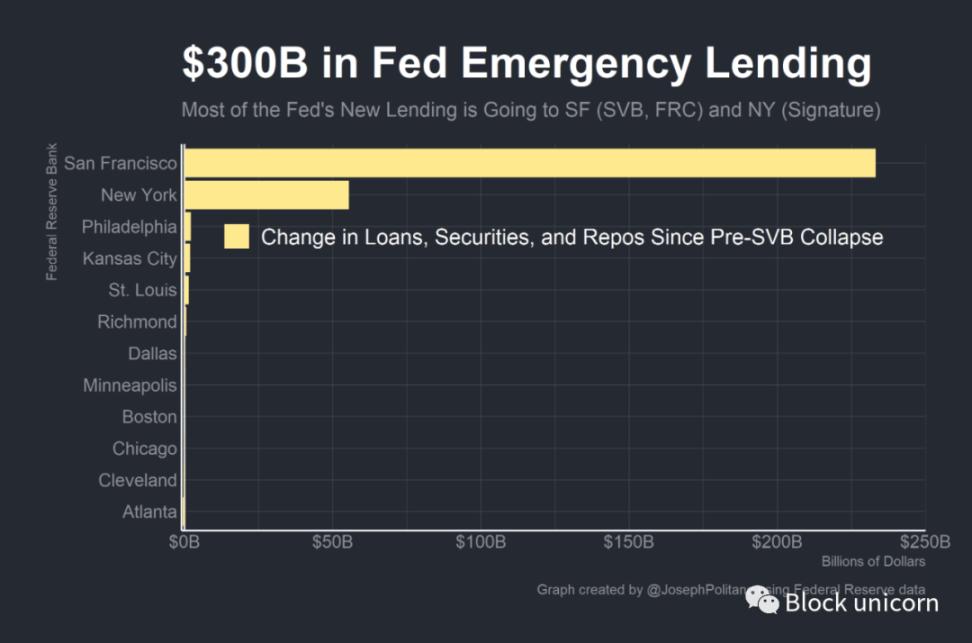

The Fed intentionally does not immediately disclose who they are lending to and how much they have borrowed, but by looking at data on the total assets of the regional Fed banks, we can get a sense of who is getting liquidity from the Fed. Looking at programs that include discount window loans and BTFP funding, we can see that loans are not evenly distributed across the country, but heavily concentrated in the two Federal Reserve Banks. Assets at the San Francisco Fed, which has jurisdiction over SVB and First Republic Bank, rose by $233 billion, and assets at the New York Fed, which has jurisdiction over Signature, rose by about $55 billion. That doesn't necessarily mean that all the lending is concentrated in the three banks of SVB (Silicon Valley Bank), Signature Bank , and First Republic Bank—several West Coast regional banks have also struggled, and the New York Fed's interest in many is not necessarily only in the U.S. Financial institutions in New York (e.g., most foreign banking organizations) have jurisdiction - but this does mean that the crisis didn't necessarily lead to banks across the country borrowing from the Fed.

Not much has been borrowed through the Fed's dollar swap lines, a facility foreign central banks can use to make dollar-denominated loans to foreign banks. While the recent weakness in foreign financial institutions such as Credit Suisse may soon require the use of swap lines, the current deactivation of such swap lines means that the crisis has so far been largely contained in the United States, with the Fed emergency The main recipients of the funds were U.S. banks that borrowed from the discount window.

Understanding the New Era of the Discount Window

In many respects, the risk to the banking system posed by the SVB collapse and its aftermath caught the Fed off guard. Regulators have loosened policy on smaller "regional" banks, mistakenly believing that their failures pose no systemic threat to the financial system, while the Fed believes that interest rates have not been raised fast enough to damage the banking system steady state. However, in a way, they were very prescient - the Fed has been trying to institutionalize discount window reforms aimed at improving financial stability after the early covid financial crisis. Today, the unprecedented use of the discount window partly reflects the expected outcome of these reforms.

In the early days of the Fed, many institutions basically kept borrowing from the discount window, so the window was more of a regular monetary policy tool than a backstop for emergency support for the financial system. By the late 1920s, the Fed was increasingly opposed to the use of the discount window, arguing that excessive reliance on the discount window created financial stability risks, and in an era when the Fed set policy rates by injecting or removing bank reserves from the system, this tool Outdated and useless. Every time banks borrow from the discount window again, the Fed tightens the requirements, adds surcharges, or restricts lending more to push banks away from the discount window. This leads to a serious problem - with the Fed's strong disapproval of the use of the discount window, overall utilization is very low, and any bank that tries to use the discount window to borrow in a true emergency will face a huge stigma.

By borrowing from the Fed, the banks are showing that they are in a truly desperate situation with no other options. Shareholders, creditors, depositors, and even government regulators won’t take kindly to you if they find out you used the discount window — essentially a sackable offense for bank executives. The consequence of this is that even distressed institutions that are innocently under pressure choose to take unnecessary financial risks rather than seek help from the Fed, making the overall financial system even more unstable.

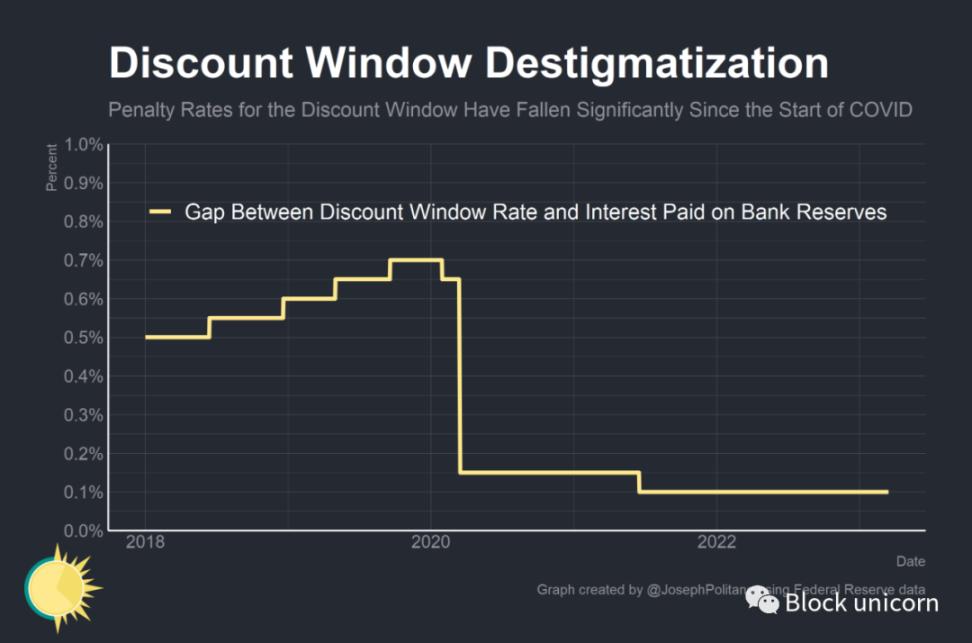

After the financial crisis in early 2020, the Fed introduced several reforms aimed at encouraging more banks to use the discount window and reducing the stigma of borrowing from the Fed. First, the maximum tenor was extended from overnight to 90 days, enabling banks to borrow for longer and more flexibly. Second, the “penalty rate” charged on borrowing from the discount window was reduced substantially so that the cost of borrowing from the Fed was no longer significantly higher than market rates—as of today, the prime credit rate at the discount window is only less than what the Fed pays on bank reserves. Rates were 0.1% higher, compared with 0.7% before the pandemic.

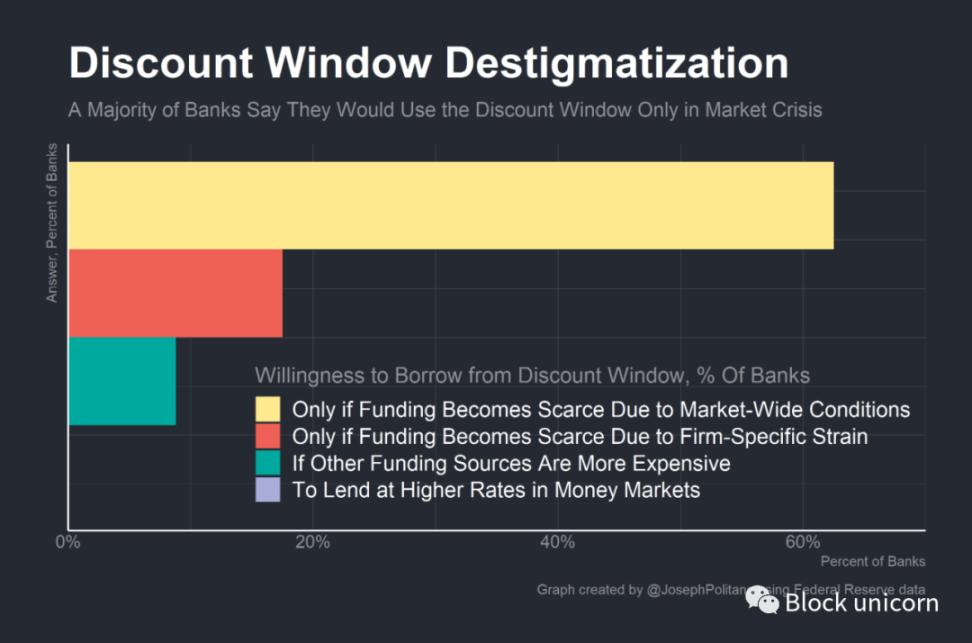

Despite the reputational damage to banks from using the discount window, the reputational damage from using the discount window has diminished since the pandemic -- more than 60% of banks said they would borrow from the Fed if market conditions made funds scarce, This was before March 2021, and before the SVB collapse, banks routinely borrowed billions of dollars from the discount window. Changes to loosen collateral requirements further after the SVB collapse may encourage more banks to use the discount window and help reduce reputational damage. That so many banks feel the need to use the discount window is a bad sign for U.S. financial health, but it is a good sign that they are using the discount window instead of trying to cope independently without the Fed's help.

Ironically, however, the BTFP (Term Financing Program) may end up inheriting the reputation-damaging problems of the discount window due to its links to the SVB debacle. However, the $11.9 billion loan balance suggests banks are not overly concerned about the image of borrowing from the Fed, a positive sign for financial stability. If credit damage becomes an issue again, the Fed may try to revive or adjust the "term auction mechanism" - a Great Recession-era program in which the Fed auctioned off a certain number of mortgages to banks to prevent any one financial institution from Requiring borrowing from the Federal Reserve suffers from reputational damage. However, the Fed may view continued use of the discount window as a sign that the system is working as intended for the time being.

in conclusion

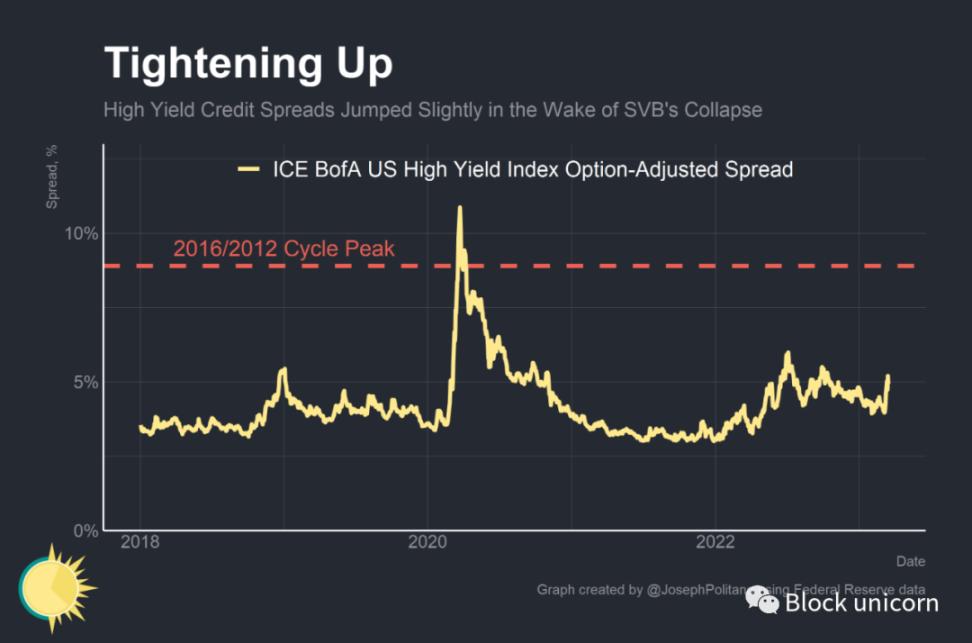

So far, the Fed's intervention has succeeded in preventing a catastrophic tightening of financial conditions - although corporate bond spreads have increased markedly since the SVB's failure, indicating that borrowing conditions have become more difficult for major companies, they are still below The most recent July and October highs. But that shouldn't be misinterpreted as a sign that the crisis is over -- First Republic, for example, had to take in $30 billion in deposits from several other large banks in addition to borrowing billions from the Federal Reserve. Several banks are still at risk, and the impact of the Fed's emergency measures to stabilize the banking system may take time.

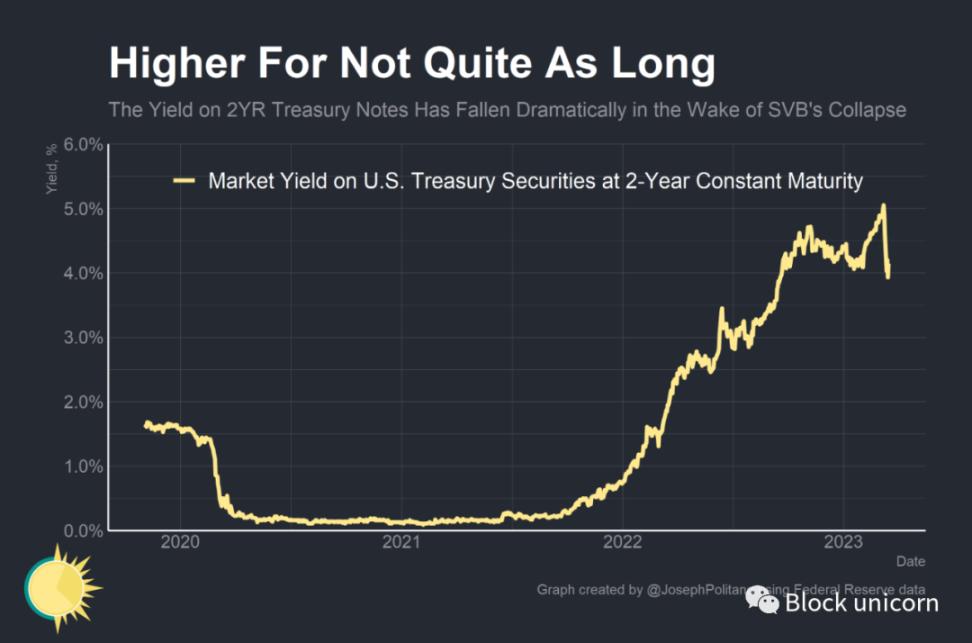

However, one thing is clear - the lingering fallout from the SVB crisis has worsened financial conditions while also dampening near-term interest rate expectations. On March 8, interest rate futures markets were pricing in a 0.5% rate hike by the Fed at next week's FOMC meeting as the most likely - and today, they see a high probability of no rate hike at all. The yield on the two-year note fell more than 1% and has been volatile over the past week. Banks are already tightening lending amid worsening economic forecasts - and the events of the past two weeks are unlikely to get them any more excited about the economic outlook ahead. Whether the Fed's emergency efforts will be enough to restore confidence in the financial system will depend on whether banks can restore stability without creating a credit crunch large enough to bring down the U.S. economy.