Suppose you have a large number of objects that can be sent by users, that all (if valid) need to be broadcasted so that they can be discovered and included by some final builder node. Suppose also that the validity condition can be expressed in a STARK, and we are in a post-quantum environment where elliptic curve SNARKs will not work.

This applies in at least three use cases in Ethereum:

- Post-quantum execution-layer signature aggregation, especially if users are using privacy protocols

- Post-quantum consensus-layer signature aggregation, to handle a large number of validators

- Broadcasting blob roots, in a distributed block construction model where we assume that the total number of blobs is too large for a builder to fully download, and so the builder must download roots from blob submitters and then use DAS to verify their availability. The STARK verifies that the erasure coding was computed correctly

The problem: STARKs are expensive, taking up 128 kB even in highly size-optimized implementations. If each object sent by a user was broadcasted to everyone along with the full 128 kB of STARK overhead, the bandwidth needs (both to intermediate mempool nodes and to the builder) would be overwhelming.

Here is how we can solve this problem.

When a user sends an object into the mempool, they can send that object along with either a direct proof of validity (eg. one or more signatures, EVM calldata which passes some validation function), or a STARK proving validity.

Mempool nodes follow the following algorithm:

- They passively wait and receive objects from users. When they see an object, they validate its proof. If the proof is valid, they accept it.

- Every tick (eg. 500ms), they generate a recursive STARK proving validity of all still-valid objects they know about. They forward this proof to their peers, along with sending each peer any objects (without proofs) they have not yet sent to that peer.

The logic of the recursive STARK is as follows. The public input is either a bitfield or a list of hashes, representing the set of objects the proof proves the validity of. The proof then expects:

- 0 or more objects, with their proofs of validity (either direct proofs or STARKs)

- 0 or more other recursive STARKs of the same type

- A bitfield of hash list of objects to discard (this allows throwing away expired objects)

The proof then attests to the validity of the union of all objects and all public inputs of recursive starks fed in to it, minus the objects that are discarded.

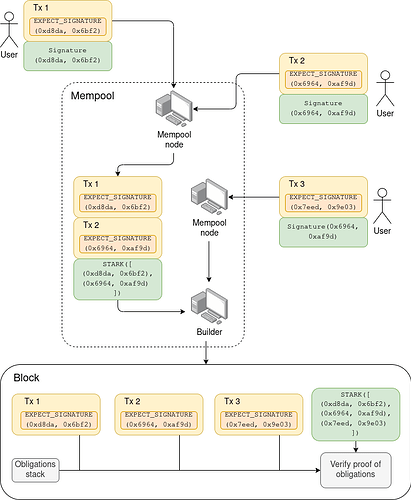

In diagram form (here, for the execution layer signature aggregation use case):

In this example, the first mempool node sees Tx 1 and Tx 2 (with direct proofs), and creates a recursive STARK proving that {Tx 1, Tx 2} are valid. The second mempool node sees the message from the first node, which contains Tx 1 and Tx 2 (without direct proofs) plus the STARK, and it also sees Tx 3 (with a direct proof), and it creates a recursive STARK proving that {Tx 1, Tx 2, Tx 3} are valid. It sends this along to its peers, of which one is a builder, who receives and includes it.

If the builder receives multiple messages containing non-fully-overlapping sets of objects and the builder wants to include both, the builder can themselves make a recursive STARK combining them. The builder can also discard to throw away any objects (here, transactions) that they see are no longer valid for inclusion.

The total overhead of this scheme is:

- Each object, without its proof, gets broadcasted to each node. This has the same bandwidth as the status quo today, except we can strip out signatures.

- Each node has extra inbound and outbound bandwidth equal to the size of one STARK per tick, multiplied by its number of peers (eg. with 8 peers and 500ms ticks, that’s 128 kB * 8 / 0.5 = 2 MB/sec). This is constant, and does not increase as the number of objects that users send in grows.