Author: Peter Todd

Source: https://petertodd.org/2025/coinjoin-comparison

The original article was published in July 2025.

The Kruw project asked me to analyze and respond to Yuval's "nothingmuch" post by Kogman discussing centralized, round-based deanonymization attacks, specifically targeting the WabiSabi protocol used by the Wasabi wallet. Kogman had been involved in the design of WabiSabi but "left in protest before its release. "

Kogman claims, "This software is fundamentally unsuitable for its design goals; if you're not willing to entrust your private information to the coordinator, you shouldn't use it." However, Kogman doesn't provide a clear engineering basis for this opinion. Therefore, I believe it's valuable to conduct a security analysis of CoinJoin's features, the attacks it prevents, and whether the two current CoinJoin implementations—Joinmarket and Wasabi—can defend against real-world deanonymization attacks.

Disclaimer: Kruw paid for my research time at my usual open-source event consulting rates; they run the most popular Wasabi coordinator . I personally use Wasabi, and in fact, I received payment related to this article directly from Kruw's Wasabi wallet.

1. Background

The concept of “Coinjoin” first gained widespread recognition thanks to Gregory Maxwell’s 2013 paper. The basic principle is simple: if two or more people jointly create a Bitcoin transaction, the “ input ownership identity ” heuristic fails because not all inputs to the transaction actually belong to the same person. The simplest way to construct a coinjoin transaction is to have two or more parties who already have the willingness to pay combine their respective transaction inputs and outputs into a single transaction. Even this simple approach yields small cost savings: the parties share bytes in the transaction “header,” thus reducing overall transaction fees.

However, this simple technique sacrifices privacy for two important reasons:

- External observers can often correlate the inputs and outputs based on the specific monetary characteristics of the inputs and outputs.

- Participants in coinjoin will know which inputs and outputs belong to other coinjoin members.

For example, consider a transaction like this:

| Enter (amount) | Output (amount) |

|---|---|

| 61,836 | 53,467 |

| 98, 902 | 61,736 |

| 45, 235 |

If you suspect this is a very simple two-party coinjoin transaction, then it is reasonable to guess that the first input and the second output belong to the same person, and that the funds in the second input went into the first and third outputs.

The above analysis leads us to two main threat models:

- Passive Blockchain Analysis 4 : Attackers use publicly available blockchain data, possibly combined with other data, to attempt to deanonymize transactions through passive analysis.

- Active (Syllabic) attack: The attacker actively participates in coinjoin transactions to obtain data that is not publicly available. We can assume that an active attacker would also use passive blockchain analysis.

Interestingly, based on my private conversations with current and former employees of Chainalysis and its competitors, real-world blockchain analytics actually disdains running even the most basic statistical analyses, such as deanonymizing simple coinjoin transactions. In fact, they don't bother with any reasonable statistical analysis: their products are highly unscientific and rely on essentially intuitive and rudimentary heuristics to "label" outputs rather than actually figuring out the probability that a given output is related to a particular activity. I even met a founder of a Chainalysis competitor who, drunk after dinner, told me that his product was a complete scam, doing absolutely no real analysis: its true purpose was to provide excuses for police arrests and to allow exchanges to meet "AML/KYC" requirements. Chainalysis itself has been actively concealing the true workings of its products, for example, in court; it's quite possible that Chainalysis's products are actually unreliable.

Conservatively speaking, recent court documents revealed that Chainalysis ran a Tornado Cash relay, presumably attempting to collect data on Tornado Cash users. While Tornado Cash is a very different technology from CoinJoin, if Chainalysis is taking proactive steps to deanonymize Tornado Cash users, they may also be taking proactive steps to deanonymize CoinJoin's implementation.

(Translator's note: "Tornado Cash" is a privacy-enhancing service that runs on the Ethereum blockchain; its principle is that users deposit standardized amounts of funds and withdraw them from the pool after a period of time using bearer credentials.)

Regardless of whether our adversaries are frauds or not, we should assume they are truly capable.

1.1 K-Anonymous Sets

Privacy tools typically analyze this using the concept of a "k-anonymity set": a set of $k$ individuals who are anonymous and indistinguishable from others in the set. Cryptocurrency apps like Coinjoin add an extra element: the amount of money from which your funds originate. This is particularly crucial if you try larger sums of money with Coinjoin: larger amounts result in a smaller k-anonymity set because fewer people have enough funds to potentially be part of that set.

1.2 Tor

The Tor network is an onion-routed network. The Coinjoin scheme uses Tor to achieve anonymity: as long as Tor nodes keep their promise (not to keep logs), Tor allows Coinjoin clients to communicate anonymously even in the most stringent threat models; this is important for JoinMarket's security model and extremely critical for Wasabi's security model.

Tor is not decentralized. While a large number of volunteers run individual Tor nodes, the Tor consensus itself—the list of Tor nodes—is maintained by a centralized set of " directory authorities " who can decide for themselves who counts as a Tor node or not.

2. Important Coinjoin Scheme

Only three important coinjoining schemes have been actually implemented and are currently operational. Each of them uses a completely different approach, with its own advantages and disadvantages.

2.1 Payjoin

This is a two-party protocol that allows a payer (sender) and a payee (receiver) to create a coinjoin transaction containing payments they each intend to send. Such a transaction can outperform input ownership identity heuristics because it includes both the payer's and payee's funds in the transaction. Because payjoin is a protocol, many wallets already support it, including two other coinjoin implementations we'll discuss next: JoinMarket and Wasabi.

The Bull Bitcoin mobile wallet is a good example of how and when payjoin can benefit. Developed by the Bull Bitcoin exchange , the wallet aims to solve two key problems:

When an exchange's customers buy Bitcoin, each purchase creates a UTXO. Payjoin allows previously purchased UTXOs to be merged with the most recently purchased BTC. As a result, when spending Bitcoin later, only one input needs to be provided to the transaction (i.e., the merged UTXO), thus reducing transaction fees and preserving privacy.

When selling Bitcoin, coinjoin transactions can save on exchange fees by merging one or more existing UTXOs (combined with the currently sold UTXO). Furthermore, in the future, payjoin will enable payment cut-through , further reducing fees. And clearly, both parties can potentially benefit from the expanded k-anonymity set.

(Translator's note: "cut-through" means that no matter how complex the transaction process is, only the initial state and the final state are published in the end. For example, if n individuals who each have a portion of the payment need participate in the creation of a transaction, the final output of the transaction is the final state after the settlement of all parties. The order and details of the negotiation process will not be exposed in the form of the transaction.)

Because payjoin is a two-party agreement, proactive attacks are irrelevant: the other party in your payjoin transaction will always know which inputs and outputs belong to you. Furthermore, Sybil attacks are meaningless: after all, you're payjoining with someone you already intend to transact with.

In reality, payjoin transactions are generally identifiable based on the " unnecessary input " heuristic, which assumes that wallet software will only provide the minimum amount of input needed to execute a payment, thus guessing the payer and payee. This assumption isn't always correct, as some wallets do indeed add unnecessary input for UTXO management and privacy. Secondly, not all payjoin transactions can be analyzed this way. Differences in transaction patterns, such as the decryption process between Bitcoin exchanges and typical Bitcoin hoarders, may be sufficient to identify the inputs and outputs of both parties. However, the fee savings offered by payjoin are a compelling reason for all on-chain wallets to support it.

We will no longer discuss payjoin, as it offers the obvious benefit of reduced transaction fees for all on-chain wallets—including coinjoin wallets—without significant drawbacks (aside from implementation complexity). If you want the object you want to pay on-chain to offer the coinjoin option, then there is no reason not to use payjoin.

2.2 JoinMarket

This protocol aims to become a taker-placer protocol, where takers pay one or more placers to improve their transaction privacy by having placers contribute their inputs and outputs to the transaction (and receive payment); takers are also responsible for paying transaction fees.

If the order placer contributes arbitrary (valued) inputs and outputs, no privacy enhancement is provided because the inputs of both the order placer and the order taker can be easily identified by matching amounts. Therefore, instead, the order placer must contribute outputs of equal value to the order taker's payment outputs. The idea behind this is that by having a transaction have multiple payment outputs of the same value, we obtain a k-anonymity set containing these outputs.

Below is a very simple example of a JoinMarket trade, which I created for this trade. It has only one taker and one place order, and the trade ID is " 4f11…8b7d ":

| Enter (amount) | Output (amount) |

|---|---|

| 148,798 | 46,981 |

| 1,448,113 | 100,420 |

| 1,347,800 | |

| 100,420 |

At first glance, this output worth 100,420 satoshis has an anonymous set of $k = 2$: this output has two such outputs. But suppose you are the recipient of the first 100,420 satoshi output. Now, test your knowledge: where did this money come from? Based on how JoinMarket works, it's reasonable to assume I'm the taker who paid you, and the other participant in the transaction is the order placer. Since I must be the taker, I must pay a fee for this transaction and also pay a fee to the order placer.

With this assumption, you can easily deanonymize my input—by reasonably guessing which input matches which zero-making output; it only requires some simple arithmetic:

$$

\begin{align}

148798 - 100420 - 46981 &= 1397 \

1448113 - 100420 - 1347800 &= -107

\end{align}

$$

Clearly, the first input came from the taker, as it contributed 1397 satoshis of net value to the trade, while the second input received 107 satoshis from the order placer. Since I was the one who made the trade, I can confirm that this is correct.

Even though I paid the 107 satoshis order fee and the 698 satoshis block confirmation fee, I still didn't gain any more privacy!

This problem isn't unique to our simple test trade. In most cases, even with multiple order placers, takers can still be identified using this analysis. The root of the problem is that JoinMarekt is a market: takers and order placers have completely different roles, therefore their inputs and outputs can be identified based on the fact that "takers have to pay order placers."

In a sense, JoinMarket's economic mechanism is a complete regression: in a typical scenario—where a taker pays multiple placeholders—the placeholders might gain privacy improvements by providing a k-anonymity set of all placeholders as bait.<sup> 6</sup> However, the taker—who pays a significant fee for the service—usually does not receive any privacy benefits.

When I started writing this article, I hadn't even noticed this issue. But I later discovered that it had already been discussed in detail on the bitcointalk forum almost a decade ago, shortly after the initial launch of JoinMarket. However, its importance doesn't seem to have been fully recognized.

While JoinMarket may have other interesting aspects—such as its use of fidelity bonds to counter Sybil attacks—its primary functionality falls short of expectations. Therefore, we will not discuss it further later; I do not recommend using JoinMarket unless it is redesigned.

2.3 WabiSabi Protocol and Wasabi Wallet

The WabiSabi protocol is a multi-step coinjoin protocol implemented by the Wasabi wallet . There is also a BTCPay Server plugin that uses the WabiSabi protocol, but it is no longer maintained. Besides the Wasabi wallet, I am unaware of any other WabiSabi implementations, so in this article, I will use "Wasabi" to refer to this protocol and the Wasabi wallet implementation. Finally, although the Wasabi wallet previously had a 1.x version, it is now deprecated, so we will only refer to its current 2.x version.

Wasabi relies on amount decomposition to achieve a k-anonymity set among multiple users. The privacy of funds deposited into Wasabi is protected by one or more coinjoin rounds , where a (user-designated) centralized coordinator coordinates multiple users to coinjoin their funds.

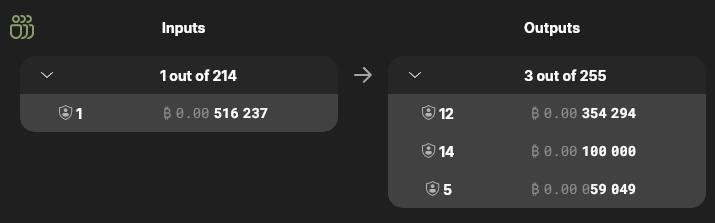

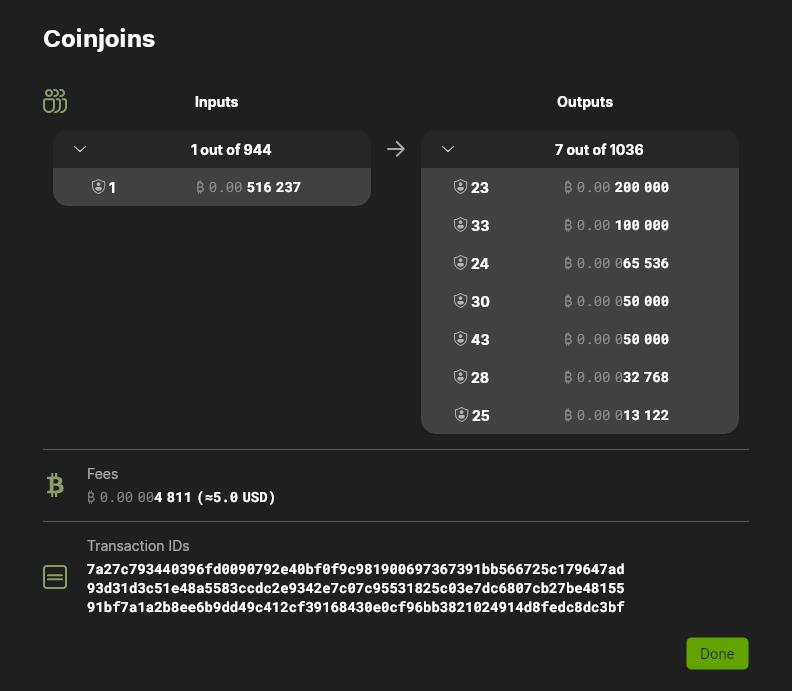

To write this article, I created a new Wasabi wallet and deposited 516,237 satoshis. I then authorized Wasabi to use the coordinator at https://coinjoin.kruw.io/ to coinjoin these funds using the "fastest speed" coinjoin strategy. Here are my inputs and outputs for participating in my first coinjoin round, with transaction ID " 7a27…47ad ":

To achieve a k-anonymity set, my Wasabi wallet decouples deposited amounts into multiple standardized denomination outputs (8 ) and distributes them among other participants in the same coinjoin round. For example, my output with a denomination of 59,049 satoshis is one of five different outputs of 59,049 satoshis for that transaction, forming a k-anonymity set of approximately 5; while my output with a denomination of 100,000 satoshis is one of fourteen such outputs, placing it within a k-anonymity set of approximately 14.

As you may have noticed, there's a shield to the left of each output entry, and a number next to it. Wasabi tracks the " anonymity score " for each UTXO. It measures the approximate size of the k-anonymity set that Wasabi believes can be provided in each coinjoin round—not absolutely precise. You can configure anonymity score targets for your coins in Wasabi, and Wasabi will continuously run coinjoin rounds until all your (economically spendable) coins reach your target. In this test wallet, Wasabi ran a total of three coinjoin rounds to ensure all outputs reached their targets.

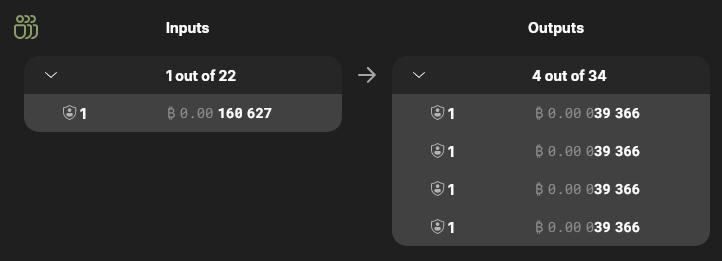

Importantly, the anonymity score takes into account the total value input and output composition of other participants. For example, in the transaction ef4a…62d3 , I deliberately used a less popular coordinator—with fewer participating users. Because of the lack of other participants, Wasabi calculated the anonymity score for my output as 1.

Because Wasabi uses a centralized coordinator, implementing very large coinjoin transactions (with hundreds of inputs and outputs) is straightforward, provided you use a popular coordinator. Most denominations will have a dozen or more seemingly identical outputs. In this case, a relatively large anonymity set can be achieved with relatively low fees, making Wasabi quite cost-efficient. Unlike JoinMarket, because all participants (except the coordinator) participate equally, there is no (known) method to perform a passive blockchain analysis attack—matching inputs and outputs with a probability exceeding k-the intrinsic probability of the anonymity set.

2.3.1 Round Structure and Cryptography

One way to achieve all of the above using a centralized coordinator is to have each participant directly tell the coordinator what inputs and outputs they want to use in the coinjoin. The coordinator can then construct a transaction containing all the requested inputs and outputs for the participants to sign. If Wasabi works this way, the final coinjoin transaction will be resistant to passive blockchain analysis. Secondly—assuming a large number of participants in each round—it becomes very difficult for a participant to determine which inputs and outputs belong to which other participant through process of elimination.

However, you must trust the coordinator to keep the secret (the relationship between input and output). That's the problem. There are clear reasons on both sides: not only do we prefer the coordinator not to know the secret, but an honest coordinator also prefers to know nothing about it at all.

Wasabi mitigates this problem through a multi-stage protocol: participants use multiple identities via an anonymous communication mechanism (such as Tor). For a full description, you can read this manual . However, I will summarize it into the following four stages:

- Input registration: Participants tell the coordinator which input they want to use and then receive a chaumian e-cash token, essentially unique to that round (one for each input). Participants use pseudonyms like "Alice" at this stage; generally, Tor is used to obtain anonymity.

- Output registration: Using a new identity, for example, through a new Tor connection, participants send their input tokens to register the outputs they wish to appear in this coinjoin round.

- Signature: Now, the coordinator has constructed the complete transaction, and each participant signs the transaction; this stage reuses the identities used in the "Entry Registration" stage.

- Attribution Phase: If not all participants sign, CoinJoin will retry among those who successfully signed. Coins from non-signing participants will be temporarily blacklisted to make a DoS attack more costly.

Here, privacy is guaranteed by using two different identities (sets) during the input and output registration phases, and by using round-specific, e-cash-like tokens. Privacy guarantees against proactive coordinator analysis heavily rely on Tor: if the Tor connection can be deanonymized by the coordinator, the coordinator can correlate inputs and outputs.

3 Attacks on multi-party coinjoin schemes

For the purposes of this article, we will assume that the underlying cryptography of the e-cash-like token used by Wasabi is correctly implemented and used; I am unaware of anyone who has argued that this assumption is invalid. Accordingly, we will delve deeper into the details of the security model of the coordinator-blinded multi-party coinjoin scheme, as well as Kogman's criticisms of Wasabi.

3.1 Witch Attack

If the coordinator cannot link the inputs and outputs, can the above coinjoin scheme be deanonymized? Of course! A " Syllabus attack " can be used: if an active attacker can successfully "overwhelm" a coinjoin round with a large number of participant identities, making the attack target the only real user in the coinjoin round ( every other participant is controlled by the attacker), the attacker can deanonymize the coinjoin round through a simple process of elimination.

This attack is fundamentally flawed for any type of open, multi-party coinjoin system—where anyone can participate anonymously.<sup> 9 </sup> In fact, this attack could even—theoretically—be applied to systems like Monero and Zcash. The only question is, how expensive would such an attack be?

A typical Wasabi Round 10 transaction, using the Kruw coordinator, has a size of approximately 25,000 vB and incurs a fee of about 50,000 satoshis. At the current exchange rate, that's roughly $50. Furthermore, Wasabi runs dozens of coinjoin rounds daily.

An adversary attempting a direct Sybil attack, overwhelming each coinjoin round with numerous inputs and outputs to isolate the victim, could potentially spend thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars daily on transaction fees. Furthermore, since millions of dollars worth of BTC are typically coinjoined in each round, a convincing attack would require obtaining millions of dollars worth of BTC to simulate the attack.

There is no evidence that such an attack is taking place. Of course, no government or other entity has publicly claimed to be running such an attack; and in my private conversations with people involved in the blockchain analytics industry, I have heard absolutely nothing about such an attack.

Ironically, if such an attack were to occur, it could arguably enhance the privacy of coinjoin participants who are not the target of the attack (at least temporarily). This implies that some entities are spending significant resources running coinjoin simply to keep the data for themselves (at least temporarily).

3.2 Targeted witch attacks

So, could witch attacks be cheaper? Perhaps with the involvement of a coordinator. In this section, we assume that turn consistency remains constant; in the next section, we will discuss the case where turn consistency cannot be maintained.

(Translator's note: The "consistency" here should be understood in the context of distributed systems: at the end of the process, all participants obtain the same result.)

Any multi-party coinjoin scheme will use some type of input registration mechanism, as well as some type of "round." If an attacker—including the coordinator themselves—can guide different users to participate in different rounds, then it becomes much cheaper for the attacker to launch a Sybil attack. For example, suppose an attacker keeps trying to track a set of coins (containing one or more coins) until that set of coins enters a coinjoin: instead of Sybil attacking all coinjoin rounds, it's more efficient to attack only the coinjoin rounds that spend those coins.

In Wasabi, without the coordination of a coordinator, an attacker can only repeatedly try to join one coinjoin round after another, then disconnect after finding that the round does not contain the target input. Because Wasabi uses a blacklist mechanism, this attack requires a large amount of coins, as joining a round that cannot be used to carry out the attack will result in some coins being blacklisted and unable to be used in subsequent rounds.

Because a single Wasabi transaction is extremely expensive, such an attack would come at a high cost even if successful: in my transaction above, a Sybil attacker would still have to pay a $140 fee to deanonymize me in order to isolate me; and they would also have to be able to control multiple groups of BTC worth $1 million (to participate in coinjoin rounds).

Furthermore, this attack involves an inherent trade-off between the information gained and the ease of disruption/detection: if the attack consistently executes the Sybil attack to the point that only one other user (the real user) remains in each round, then the attacker will destroy all coinjoin activity at that coordinator's location. This is highly suspicious! Conversely, if rounds involving spending non-target coins also succeed, it means that rounds involving spending target coins will also include non-target wallets, thus reducing the information gained from this attack.

With the cooperation of a coordinator, this type of attack requires far less capital and can be much more successful. First, let's assume the attacker knows all the coins the target wants to coinjoin.

The attacker participates in each round, registering their own witch coins as input. If other participants register coins that are not the target , the attacker withdraws, resulting in a responsible round with no witch coins. Because the attacker "cooperates" with the coordinator, these witch coins are not blacklisted and can be reused.

If other participants register the target coin, the coordinator prevents non-target coins (other than the witch coin) from participating in the same round. From the perspective of non-target participants, this appears to be merely a temporary glitch in the coordinator's behavior. Either the target coin registered immediately, resulting in a "successful" round; or (if a non-target coin joined first) the coinjoin succeeded after an attribution round. In either case, the final transaction involves only the witch attacker and the target, thus easily deanonymizing the transaction.

Such an attack, while still costly to form a convincing coinjoin round, still requires the attacker to pay transaction fees for their inputs and outputs. However, it can be accomplished with far less available funds because blacklists are no longer an obstacle; and if blacklists are made public to other participants, detecting attacks colluded with malicious coordinators becomes much easier.

3.3 Address reuse after Coinjoin failure

Ideally, addresses should never be reused. Like almost all wallet software, Wasabi uses a deterministic wallet model: addresses are deterministically generated from a seed. However, the problem lies in the " empty address limit ": the length of a consecutive queue of empty addresses that the wallet software allows before stopping the balance scan when reconstructing a wallet from a seed.

Currently, if a coinjoin round fails completely—even the attribution phase cannot produce a valid transaction—Wasabi will use the same output address in subsequent coinjoin attempts.

So what can an attacker learn from this? Suppose we have a round that fails, with two or more (real) participants. The coordinator and all participants, during the round, know the inputs and outputs that all participants collectively want. The inputs and outputs (correlations) that individual participants want are protected by a k-anonymity set because there are multiple participants.

Now suppose that after the round fails, one or more participants join a subsequent coinjoin round. Unless it is the exact same group of participants from the previous round trying to join the subsequent round, address reuse breaks the k-anonymity set: if the inputs and outputs of the current round intersect with those of the previous failed round, it means that the same participant is involved, which allows for the deanonymization of that participant.

The fix for this flaw is to not reuse addresses after a failed round. As of this writing, there is a public pull request (PR) that uses the flag for addresses in failed round events. However, it's unclear how this will interact with empty address restrictions.

Perhaps this problem can be solved using a technique based on " silent payments ." This way, the new output address for a coinjoin round would be deterministically generated from the transaction inputs (and possibly the nLockTime field), ensuring wallet recovery regardless of the number of failed rounds. A drawback of this approach is that the seed for the Wasabi deterministic wallet will be incompatible with all other wallets: you will only be able to retrieve funds within the Wasabi wallet.

Finally, the Wasabi client supports sending payments directly within a coinjoin round via an RRC call. This saves on transaction fees (avoiding sending a separate transaction). However, this feature inherently presents the problem we're discussing: after a failed coinjoin round, such direct payments don't revert to a new address and are retried. Furthermore, aside from being a high-level feature accessible only via RPC and not exposed to a graphical user interface (GUI), the GUI doesn't provide any explanation regarding the anonymity of direct payments within coinjoin.

3.3.1 Disclosing the input set of shared ownership

Avoiding address reuse doesn't solve the second (slightly smaller) information leak: attackers can learn about a collection of coins belonging to the same owner. For efficiency, Wasabi often spends multiple inputs in a single coinjoin round. Therefore, attackers can obtain statistical evidence that different coins belong to the same owner. It remains unclear how this problem can be fully mitigated in coinjoin schemes that aim to spend multiple coins at once.

3.3.2 Information Extraction Through Invalid Rounds

A riskier but potentially more informative attack involves the coordinator using completely invalid inputs to pretend there are many Alices (when there aren't actually that many). This is risky because in the Wasabi protocol, participants know all the inputs for a round before the output registration phase—necessary for optimal coin denomination selection. Participants with access to the latest UTXO set can detect this fraud. However, current Wasabi clients do not assume access to the UTXO set and therefore cannot automatically detect this fraud.

Compared to attacks via failed turns, the advantage of invalid turn attacks is that a misbehaving coordinator can obtain better statistics about the relationship between intended inputs and intended outputs at a lower cost. However, once the address reuse problem is fixed, this attack becomes less effective because the learned matching relationships are essentially useless.

3.4 Attack Round Consistency

As mentioned earlier, while it is always possible for a Sybil attack to occur in a coinjoin round, it can be inferred that doing so would be extremely costly, as the attacker would have to pay a fee for a successful round (the resulting mined transactions).

But what if you didn't have to pay this cost?

If a coordinator can induce different participants from different rounds to sign the same valid transaction, the coordinator can reuse other participants' liquidity to perform a Sybil attack on each participant. Wasabi uses a 256-bit "round ID" to identify rounds, generated by hashing all the value involved in that round . Importantly, the start time of the input registration phase and the coordinator's identity are crucial. These two pieces of information are sufficient to uniquely identify a round. Furthermore, because all round settings are hashed into this round ID, if the round ID remains consistent, the coordinator cannot anonymize different participants through behavioral differences, as different rounds have different settings.

During coinjoin, the Wasabi client periodically requests the status of all rounds. Then, after a client decides to participate in a round, it uses that round's ID in its interactions with the coordinator . In certain situations, such as when a round is full, multiple rounds may occur in parallel; the coordinator may advertise different round IDs to different clients.

During the input registration phase, all Alices send their BIP-322 ownership certificates for their inputs to the coordinator. These ownership certificates commit to a round ID , preventing the ownership certificates from being reused in other rounds. Finally, before signing, the coordinator provides each client with ownership certificates for all their inputs. After receiving these ownership certificates, the clients verify them .

The problem Kogman points out is that verifying ownership evidence alone is insufficient: we also need to verify that this ownership evidence actually corresponds one-to-one with the script public key ( scriptPubKey ) of the transaction input that the evidence is intended to prove. Wasabi clients do not assume they have access to a valid set of UTXOs and therefore do not directly verify ownership.

If we stop here, then the ownership evidence mechanism can be fooled by "fake" ownership evidence: the real (generating evidence) public key does not correspond to the script public key of the transaction input that the ownership evidence is intended to prove.

However, Kogman failed to consider how Taproot signatures work: the signature of a Taproot input guarantees the public key of all input scripts in the transaction, meaning that any forged proof of ownership will ultimately result in an invalid signature (invalid transaction). This is simply another form of invalid input attack (which we have already discussed in section 3.3.2 above).

At this point, Wasabi still supports non-Taproot inputs because historically, many services adopted Bech32m (Taproot) addresses relatively late . Fortunately, as long as any non-attacker uses Taproot input in a Wasabi round, all inputs must have valid ownership evidence. In other words, to achieve a Sybil attack through round consistency, a malicious coordinator must have as much real liquidity as all Taproot inputs in the round (and spend the same proportion of fees), and they can only attack clients that did not contribute Taproot inputs.

Why? Because honest nodes only sign one round ID. Suppose there are three Alice participants in a round: Adams, Brown, and Turner. We assume Turner has more than one Taproot input, while the other two only have non-Taproot inputs.

For a valid transaction to occur in this round, the coordinator needs to provide Adams and Brown with correct and valid ownership proof from the Turner. However, once the coordinator does this, the TA can only give all Alice participants the same round ID, thus defeating any Sybil attack attempts, because all Alice participants will register outputs with the same round ID; all Alice liquidity is contributed to the overall set of anonymity.

Please note that such Taproot inputs can also be your inputs: given that you have contributed at least one Taproot input to a coinjoin round, you can be certain that all honest liquidity in that round will contribute to the same round ID. Payments to the Bech32m (Taproot) address are now widely supported, so it would be a good idea for Wasabi to generate Taproot deposit addresses by default; as of version 2.6.0, it hasn't done so. That said, there's a 50% probability that the output address is a Taproot address, which protects the vast majority of coinjoin, as many liquidity providers attempt to register at least one Taproot address.

3.5 k-anonymous sets of communication characteristics

Previously, Kogman raised the issue of registration latency in a GitHub issue . While Kogman did not provide a clear engineering basis for this criticism, we can infer that: a k-anonymity set of communication characteristics is important in any multi-party coinjoin scheme that attempts to achieve anonymity through identity separation at different stages.

Recall that Tor provides an anonymization equivalent to TCP streaming , routing via fixed-length relay cells. Now, imagine your internet connection is the slowest among all participants in the same coinjoin round, noticeably slower. In other words, your internet connection speed doesn't have a k-anonymity set. This is possible: the coordinator can detect this characteristic by the specific timing of data interactions and then deanonymize your inputs and outputs by observing this characteristic during the input and output registration phases.

It would be ideal if Wasabi could eventually migrate to a purely package-based data anonymity scheme—where all communication is achieved through the exchange of atomic packages with completely randomized timing characteristics. Unfortunately, such a widely used scheme with trust properties similar to Tor does not yet exist. Perhaps Wasabi could improve the current situation to some extent by increasing the use of randomized latency. But without a fully package-based communication scheme, it might be best to use Wasabi over a relatively common type of internet connection to maximize your k-anonymity set. Similarly, this problem can be improved in rounds with more participants because the k-anonymity set is larger.

Kogman also points to a related version 1 of this issue: there are subtle differences between serialization and deserialization. Wasabi utilizes JSON serialization, which is notoriously ambiguous and varies slightly across different implementations. Again, your k-anonymous set is determined by how many participants use the exact same serialization scheme. These subtle differences can also lead to the coordinator being able to correlate your inputs and outputs.

Fortunately, Wasabi has only one commonly used implementation, so in reality, this may not be a problem. However, Wasabi should ultimately transition to a fully clear, strict binary serialization protocol.

4. Conclusion

While Wasabi has many areas for improvement, it is clearly the best option for participating in CoinJoin at present. Wallets that support PayJoin deserve praise, as it offers significant benefits if both the payer and recipient (their wallet software) support it. Unfortunately, despite my willingness to recommend JoinMarket, the ugly truth is that leaving clues on the blockchain about where the money came from is a very bad mistake, far worse than any theoretically risky coordinator willing to pay a high price to betray your trust.

Think about it: Would you rather take the risk that an entity might be untrustworthy and could find a way to bypass Wasabi's cryptographic protections? Or would you rather deliberately broadcast your metadata within the blockchain to the entire world, so that anyone, now or in the future, can use it to anonymize you?

While trusted coordinators are undesirable, being able to trust your coordinator provides a double layer of protection. It would be ideal if Kruw couldn't anonymize my coinjoin transaction even if he wanted to. However , it would also be good if there were a compelling human reason why he wouldn't.

JoinMarket fails on the first metric: under normal usage, many of your transactions can be deanonymized due to fee payment deficiencies. But it also fails on the second: it relies entirely on economics and probability to select counterparties, making it easy for any bad actor with spare cash to become your counterparty and deanonymize you. This is somewhat similar to how Tor, if decentralized, would become less secure because it lacks any human element to keep bad actors out; there's no way to prove you won't be logged.

Kogman's exaggerated behavior serves as a good example of what we shouldn't do. ... (Translator's note: This paragraph only addresses the character's reputation and is not translated.)

Technology is never perfect. I don't just use Wasabi myself. I prefer to use coins after CoinJoin to open Lightning Channels and use the Lightning Network to spend my money. This utilizes two very different privacy technologies, so my privacy is only compromised if both fail.

5. Footnotes

1. [bitcoindev] reiterates its deanonymization attack against centralized coinjoin schemes (Wasabi and Samourai) , 2024-12-21 14:16, Yuval Kogman; see also local archive (OTS) ↩ ↩ ↩

2. Kogman also criticized the Whirlpool protocol used by the now-defunct Samourai wallet software. We won't discuss this protocol in this article because the Samourai wallet was intentionally made to be very insecure: it would leak the user's xpub (extended public key) by default.

3. Gregory Maxwell's article, " CoinJoin: Real-World Bitcoin Privacy, " along with his earlier post, " I taint rich! ", popularized the concept. However, the idea of coinjoin had been mentioned even earlier, for example, in 2011 ; Maxwell didn't claim any invention rights. As for the name "coinjoin," Maxwell privately asked me to give the concept a good name—and I'm very happy with the result !

4. Chainalysis is a US-based blockchain analytics company; "chainalysis" is used here as a broad term to refer to this type of activity .

5. For example, I was privately told that the clustering technique used in Sarah Meiklejohn's 2013 book, * A Fistful of Bitcoins: Characterizing Payments Among Men with No Name *, is frequently used by blockchain analytics companies. However, the method described in that paper is purely heuristic analysis, not sound statistical probability analysis, and it wasn't originally designed for these purposes.

6. This might be true in practice if the fee strategies of those placing orders differ significantly, as subsequent transactions could deanonymize them due to varying fees. However , JoinMarket randomizes fees to some extent, which usually mitigates this issue.

7. GingerWallet also forked the Wasabi wallet's source code, at a time when Wasabi's central coordinator was shut down. Because GingerWallet doesn't seem to have received much development or widespread use, we won't discuss it further .

8. 5000, 6561, 8192, 10000, 13122, 16384, 19683, 20000, 32768, 39366, 50000, 59049, 65536, 100000, 118098, 131072, 177147, 200000, 262144, 354294, 500000, 524288, 531441, 1000000, 1048576, 1062882, 1594323, 2000000, 2097152, 3188646, 4194304, 4782969, 5000000, 8388608, 9565938, 10000000, 14348907, 16777216, 20000000, 28697814, 33554432, 43046721, 50000000, 67108864, 86093442, 100000000, 129140163, 134217728, 200000000, 258280326, 268435456, 387420489, 500000000, 536870912, 774840978, 1000000000, 1073741824, 1162261467, 2000000000, 2147483648, 2324522934, 3486784401, 4294967296, 5000000000, 6973568802, 8589934592, 10000000000, 10460353203, 17179869184, 20000000000, 20920706406, 31381059609, 34359738368, 500000000000, The values 62762119218, 68719476736, 94143178827, 100000000000, and 137438953472 satoshis were carefully chosen to minimize the average number of UTXOs required to decompose common values .

9. A closed coinjoin scheme can prevent Sybil attacks by restricting coinjoin participants to a range of known entities .

10. Statistics on the Wasabi rounds have been collected and published by Wabisator , LiquiSabi , and other projects .

11. This is the worst-case scenario. If the attacker doesn't know all the coins the target wants to participate in CoinJoin, the attack will be visible because some coins will mysteriously fail to register during the input registration phase .