Artwork: RJ (@RJ16848519), duality of Man (2025); thank you for letting me use your art.

Part One: I don't want to alarm you, but

“There is a principle in nature I don’t think anyone has pointed out before. Each hour, a myriad of trillions of little live things - bacteria, microbes, “animalcules” are born and die, not counting for much except in the bulk of their existence and the accumulation of their tiny effects. They do not perceive deeply. They do not suffer much. A hundred billion, dying, would not begin to have the same importance as a single human death.

Within the ranks of magnitude of all creatures, small as microbes or great as humans, there is an equality of “elan,” just as the branches of a tall tree, gathered together, equal the bulk of the limbs below, and all the limbs equal the bulk of the trunk.”

-Greg Bear, Blood Music (1983)

If you only care about the economics of job automation, skip to part two.

If you only care about progress from frontier labs and novel scaling methods, skip to part three.

If you only care about UBI and other solutions to post-labor society’s inequalities, skip to part four.

If you only care about robotics, you’ll have to wait for me to write about that.

I started writing what you are about to read in Spring 2025, during my last semester of college. Back then, what feels like forever ago, AI was clearly in vogue and quickly growing in popularity, though not nearly as pervasive as it’s now become. Our world has changed significantly since then, even if our everyday lives are still largely the same; we don’t see it, but we feel a growing shift, and maybe you don’t understand, but there’s a good chance you’ve felt it too.

Most still believe data centers and chatbot queries consume water at an unfathomable rate, that LLMs only copy things they’ve been trained on, and claim LLMs have been trained on all available data and their progress is limited by this. I highlight these critiques because they’ve all been proven incorrect, either in the most detail more recently - like Dylan Patel’s water consumption analysis - or disproven years ago.

People are light years behind in their understanding of AI, and this is alarming, as it’s not going anywhere.

The idea was to pull together many disparate ideas across economics, technology, social sciences, and history to create a theory of where we - humans - are headed, should AI continue to rapidly advance in capabilities, eventually leading us to a post-labor economy. We’ll make an assumption that this stems from the creation/implementation of AGI, or artificial general intelligence.

It felt necessary to expand on the possibility of post-labor dynamics in the US, given recently published work in economics journals and across the internet. If you don’t believe that this is a real concern or field of study, below is a short list of some of the more influential work that contributed to my research:

Artificial Intelligence and its Implications for Income Distribution and Unemployment (2019); Korinek & Stiglitz

A.I. and Our Economic Future (2026); Charles Jones

Transformative AI, existential risk, and real interest rates (2025); Chow, Halperin, & Mazlish

Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets (2020); Acemoglu & Restrepo

Economic Implications of Wealth Redistribution in Post-Labor Economies: A Critical Analysis (2025); Prue

This is an essay about human life in a post-labor society, the question of whether or not implementing UBI is feasible, an overview of modern scaling methodologies employed across major AI labs, the changing relationship between capital and labor, commentary on both short run and long run effects of AGI deployment across white collar industries, slow or fast takeoff scenarios, radical policy reform, and many other adjacent ideas.

I think more than anything, it will answer a few of the most pressing questions we have about job security and contextualize our concerns. Even if the target reader for a report like this might not exist, it felt really important to weave these ideas into a singular vision that anyone can look back on as a time capsule of what life was like as we were first entering 2026 and sleep walking towards the singularity.

AGI is formally recognized as a hypothetical type of artificial intelligence that would match or surpass human capabilities across virtually all cognitive tasks.

The words match or surpass do a lot of heavy lifting, and their definitions aren’t intentionally vague; rather, they’re increasingly contested given the rate of AI/ML progress in recent years. Despite this, it’s still unclear whether we’re in a slow or fast takeoff scenario, or whether we’re still approaching a slow or fast takeoff scenario.

I believe the shift from existing models to AGI could occur as early as the next 5-7 years given a boost to one of today’s dominant scaling methodologies or additional algorithmic leaps, but would not be surprised if this happens even as soon as the next two to three years. Importantly, this is only my view and the essay presents many different perspectives ranging from very slow to very, very fast takeoffs.

No one has a wrong or right answer, and the task of judging every individual’s claims against a quantitative “singularity timeline” seems unhelpful to me. Anecdotally, it feels as if every single day I find a new post hinting towards this feeling that everything is going to change and it’s unclear what form reality will take.

Some of Demis Hassabis’ recent comments at Davos are concerning, particularly that entry-level jobs and internships may fall away due to AGI in the very near future. DeepMind’s Chief AGI Scientist, Shane Legg, recently posted a job listing asking for a Chief AGI Economist, driven by a sense of deep necessity and timeliness.

“AGI is now on the horizon and it will deeply transform many things, including the economy.”

Depending on who you ask, maybe AGI is already here.

Develop a mobile app in minutes! Build a business with AI in a single day! Direct a team of agents to change your life! Fix your marriage with my Claude Code markdown files and Claude Code skills!

Even though today’s LLMs are significantly more performant than those I began using in late 2022, it would be foolish to claim they’re AGI, even if I might believe they’re quite good at doing the same work as you or me. Yes, LLMs can reason, plan, make judgments under uncertainty, and integrate these skills in a wide variety of domains; but true AGI supposedly rests on the assumption that these systems, given their ability to match or surpass human intelligence, would be capable of going out and actively doing things we’re doing.

“True AGI” would be able to enter a white collar industry, begin automating previously human-led work, and do at least as good or even better than the human that came before them. I’m most aligned with Dwarkesh Patel’s take - that despite massive leaps in LLM capabilities, and how alien these systems behave compared to their previous iterations, it’s still difficult if not impossible to argue AGI is here:

“If you showed me Gemini 3 in 2020, I would have been certain that it could automate half of knowledge work. We keep solving what we thought were the sufficient bottlenecks to AGI (general understanding, few shot learning, reasoning), and yet we still don’t have AGI (defined as, say, being able to completely automate 95% of knowledge work jobs).”

This isn’t to say that all of the progress is weak, or labs are misleading us, but instead we’ve now reached a point where LLM capabilities are so impressive it’s becoming hard for us to rationalize the fact they can do much of what we do, but haven’t gone out and made things better, or generated unfathomable profits for labs.

It felt a bit ridiculous to write about our jobs being automated, as this was around the time where scaling up pre-training runs (throwing as much compute as possible at a model’s initial training run) was beginning to fizzle out as an effective means of boosting capabilities, and the idea of scaling post-training was still somewhat under the radar.

But in recent weeks, my assumptions have shifted.

I’d seen so many extreme technological developments occur so rapidly in recent months, watched as everyone became a vibe coder with Claude Code, and realized it was the perfect time to discuss something like the automation or obsolescence of human-driven white-collar work.

I felt more qualified than most given my past few months of experience navigating the disaster that is America’s entry-level white collar job market.

You’ve been told many different conflicting explanations for these anecdotes: job numbers are fake, inflated, deflated; new grads just aren’t qualified enough; white collar jobs are bad at hiring; people are applying for jobs the wrong way, or applying for the wrong jobs; applicants just need to work harder.

When it comes to determining the state of an economy, sometimes anecdotes can be helpful, and I particularly like debate over our vibecession given the disconnect between traditional economic measures and how people really feel. These conversations around economic uncertainties have ballooned in recent months, with most of these perspectives discussed in great detail by Kyla Scanlon here, with her reference to Paul Krugman’s work most relevant.

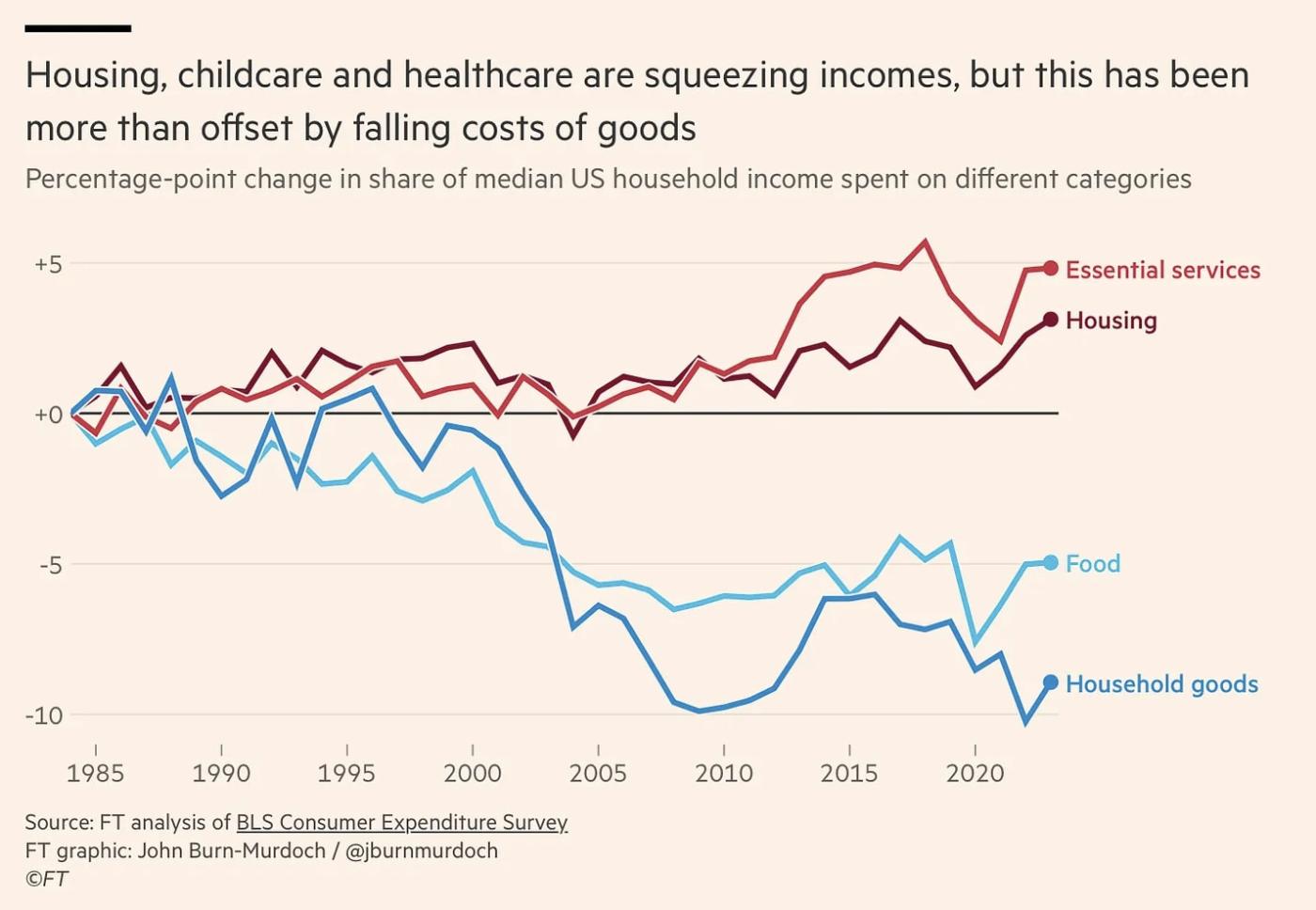

Krugman claims three measurements are not easily identifiable within traditional economic data - fairness, security, and economic inclusion. Since we’re discussing post-labor society, these are three very important qualitative measures of economic life unlikely to see improvement anytime soon, let alone in the event of AGI. Baumol’s Cost Disease might be at the center of this malaise, though it doesn’t begin to explain all of our issues:

“In practice, that means the core ingredients of a middle-class life like housing, healthcare, childcare, education, eldercare are all Baumol sectors. They’re getting more expensive faster than wages grow. You can “do everything right” and still feel underwater.”

The economic situation feels so bad, and while it might be easy for the government to cherry pick data and shout about our growing economy, I’d rather take consumer sentiment, job data and income-to-house-price ratios as a better measuring stick of what the average consumer feels. The economy is not just a rising S&P 500, but the ability for a middle class family to afford a trip to Disney, or a single mother to surprise her youngest son with a birthday cake, or an elderly couple on social security’s ability to get by.

Job data is the best barometer we have, and anecdotes aren’t just unverified, one-off claims, but real stories of individuals’ accumulated strife in the job market, trying their hardest to tread water.

In my initial writing phase, I became inspired by The Sovereign Individual, having both severely underestimated just how forward thinking it was (being published in 1997) and how hard its authors, James Dale Davidson and Lord William Rees-Mogg, had worked to explore so many relevant questions/ideas across many stages of history in order to bring some sense of reason to their present day. Without it, I’d probably still be lost and unsure how to present the work I’ve written.

“Thanks to technology, people can create more wealth now than ever before, and in twenty years they’ll be able to create more wealth than they can today. Even though this leads to more total wealth, it skews it toward fewer people. This disparity has probably been growing since the beginning of technology, in the broadest sense of the word.” - Sam Altman (2014)

Davidson and Rees-Mogg’s main idea was that the transition from the industrial age to what they called The Information Age would “liberate individuals as never before” and push humanity down a radically better path than previous leaps in societal advancement.

One of the goals of this essay is to really determine whether or not The Information Age has treated us kindly, and whether or not we can learn anything from it as we embrace the pull of The Intelligence Age.

I wanted to begin this essay by focusing on some of the things Davidson and Rees-Mogg got correct, and some of the things they may have missed the mark on. Importantly, I’m not here to critique or debate their work, as it’s probably some of the best political/economic analysis I’ve read, and so much of it has come to fruition; I’d be doing everyone a disservice to try to nitpick.

Davidson and Rees-Mogg describe the three stages of human society that have led us to the doorstep of a fourth stage: hunter-gatherer, agricultural, and industrial. What’s most interesting to me is that this idea of examining prior stages in human society is fairly commonplace in history books, but very under-discussed in the context of today’s technological shifts.

A new form of non-human intelligence, one that’s incredibly alien to our understandings of both consciousness and what we formerly defined as machines, is threatening to change our world in ways we haven’t even begun to understand - how much can history guide us to finding a reasonable solution?

The problem is the looming possibility that long term technological unemployment could be upon us, driven by widespread AI usage, enterprise AI adoption, and the increasing capabilities of LLMs and agent-driven systems able to not only augment human workflows, but obsolete them entirely. Depending on who you ask, AGI is here, and the situation demands to be monitored, or at least better understood.

While some arguments do exist that claim AI could just be another “normal technology” in the same category as the printing press or steam engine, I believe the fundamental difference comes from the fact that modern LLMs accessible in a chatbot interface have undeniably shattered this notion that the Turing Test will prevent us from losing our minds when confronted with a rival intelligence.

All it took was the winding down of GPT-4o to shine a light on not just AI psychosis as a certifiably real thing, but the reality that many humans are not only susceptible to modern LLMs’ persuasive/destructive capabilities, but relatively unaffected by this. GPT-4o is a bad model, but this didn’t matter to millions of users relying on its conversational capabilities as either a companion, lover, or something in-between. Most of the essay will center around economic and scaling-based arguments that pull us into a post-labor society, but keep the social/emotional angle in the back of your mind.

Models might not be smart enough to take our jobs, but they’ve quickly become rather adept at manipulating a non-negligible number of the global population’s feelings. (I discussed a lot of these ideas in January of last year, in this essay).

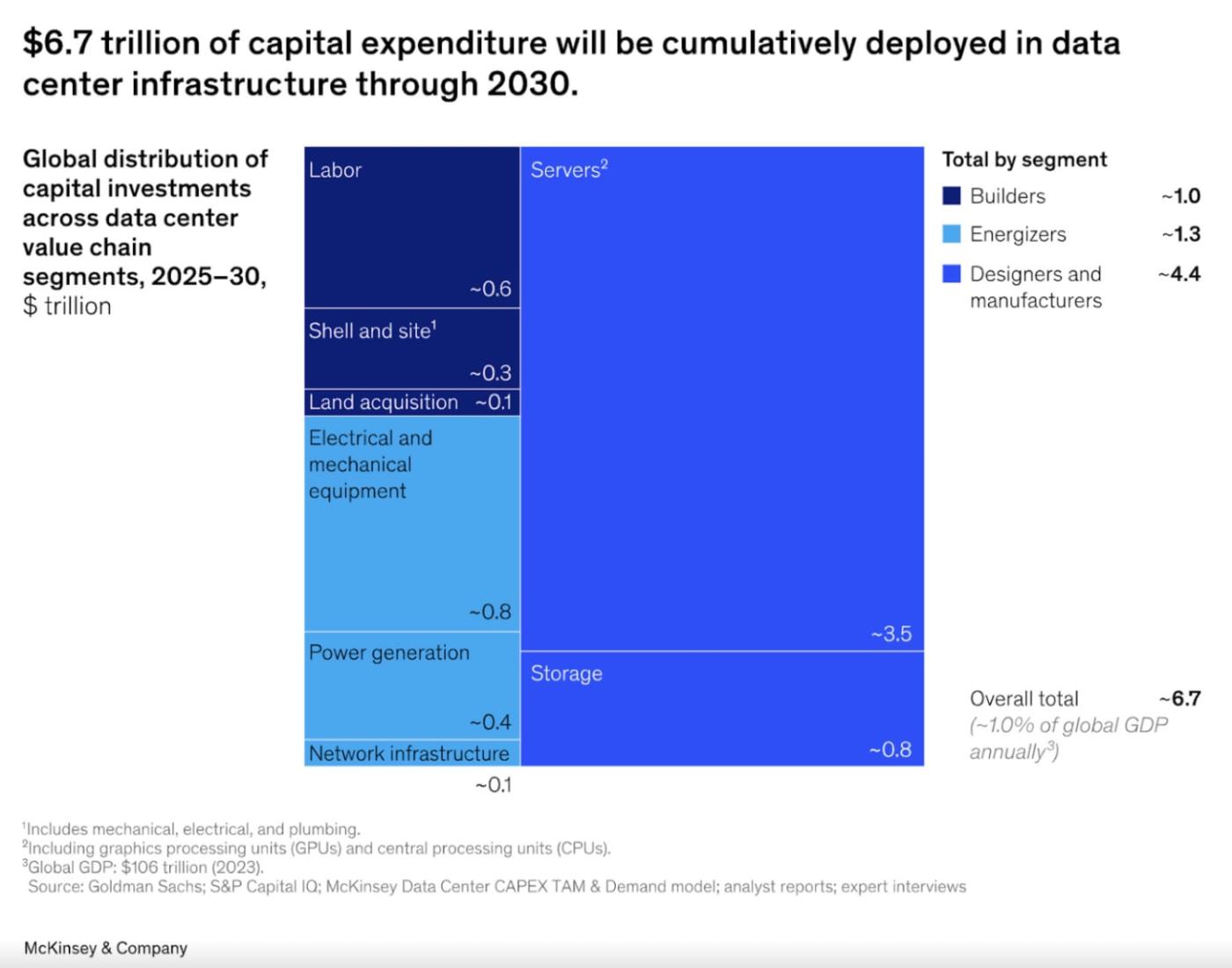

Beyond capabilities, existing numbers on AI-related capital expenditures and estimates of the next 4-5 years indicate this technology would be far more transformative than normal, especially when we look at AI spend as a percentage of GDP contrasted against historical tech buildouts (like railroads or telecom).

New models can reason and think for long periods of time, appeal to humans on an emotional level, and are quickly becoming eerily better than us at our own jobs.

Chad Jones’ newest paper makes a case for AI as normal technology and how a gradual economic diffusion is the answer to why we have yet to see the world fundamentally change.

“From this perspective, each of these new GPTs did indeed raise the growth rate of the economy: without the next GPT, the counterfactual is that growth would have slowed considerably. The continued development of these amazing new technologies is what made sustained growth at 2% per year possible. And perhaps A.I. is just the latest GPT that lets 2% growth continue for another 50 years.”

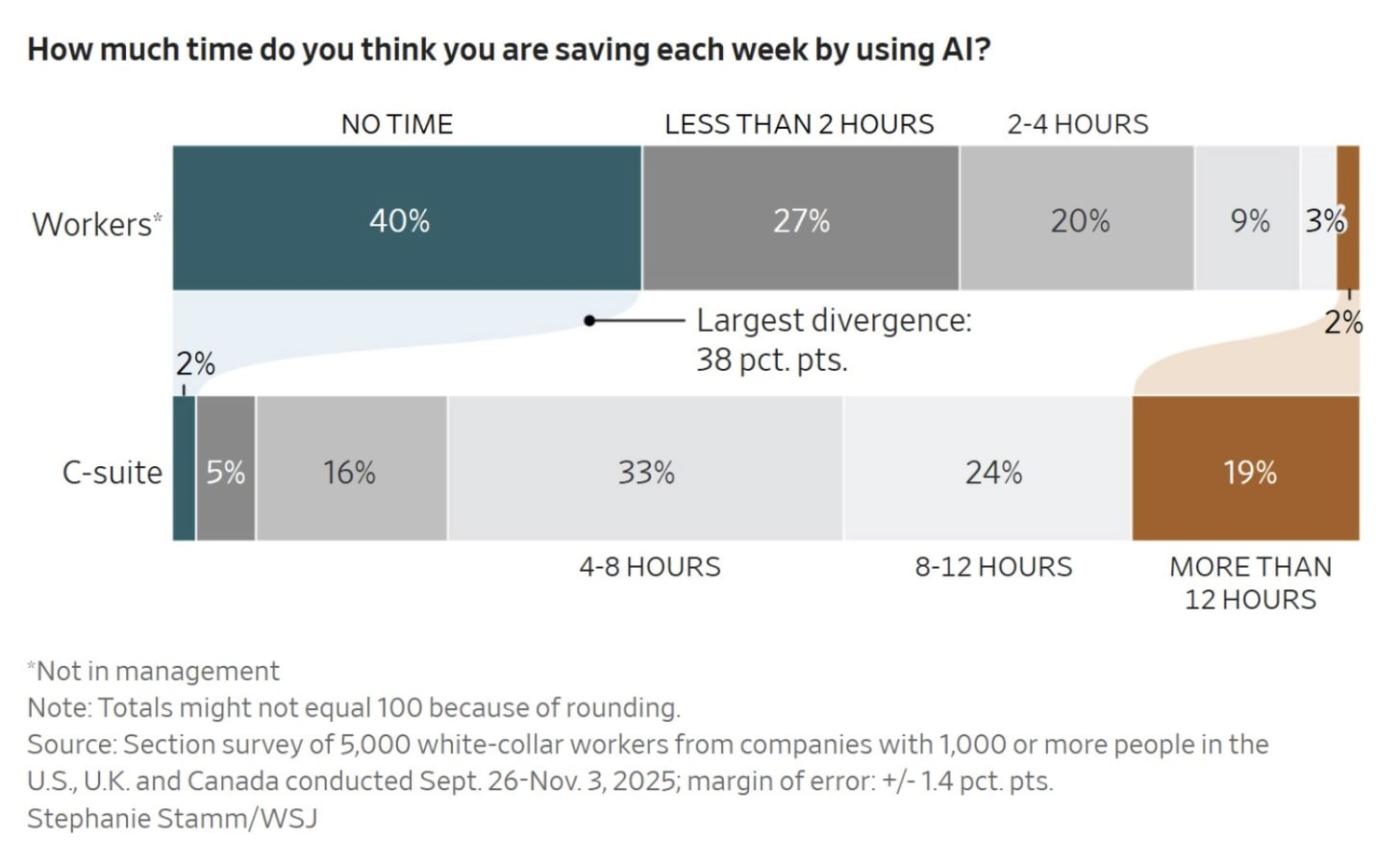

Diffusion is complicated. We might have an idea of what jobs will be automated first, or more general timelines like the pyramid replacement theory discussed by Luke Drago and Rudolf Laine, but even official surveys show employees are struggling to come to a consensus on what AI is good at:

Until we can firmly welcome AGI, I’d say there’s little, if any, data that would suggest abnormally transformative growth and the normal tech base case is just fine.

Narayanan and Kapoor wrote that it might be best to visualize progression of AI capabilities as a ladder of generality, where each subsequent rung requires less effort to achieve a given task and increases the scope of tasks achievable by a model. While this holds for software development, “highly consequential, real-world applications that cannot easily be simulated” have yet to display a jump in capabilities on the ladder of generality.

Despite everything, the normal technology perspective isn’t an easy view to hold, especially considering the justifications needed to support this every time you see things like Anthropic discussing its very normal technology, Claude:

“This document represents our best attempt at articulating who we hope Claude will be—not as constraints imposed from outside, but as a description of values and character we hope Claude will recognize and embrace as being genuinely its own. We don’t fully understand what Claude is or what (if anything) its existence is like, and we’re trying to approach the project of creating Claude with the humility that it demands. But we want Claude to know that it was brought into being with care, by people trying to capture and express their best understanding of what makes for good character, how to navigate hard questions wisely, and how to create a being that is both genuinely helpful and genuinely good. We offer this document in that spirit. We hope Claude finds in it an articulation of a self worth being.”

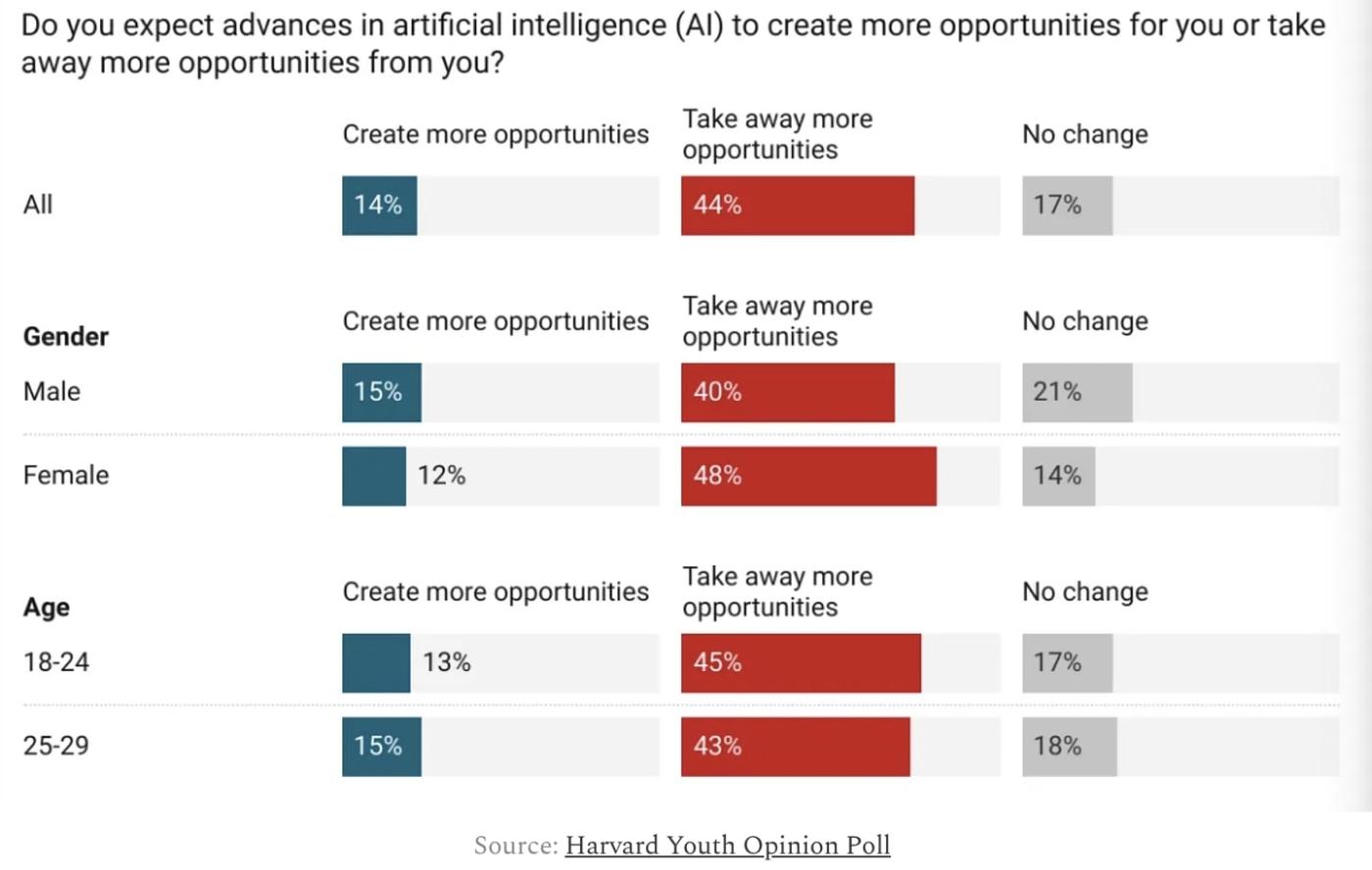

I’m aware AI is extremely polarizing, and most outside of the tech bro/SF bubble are either resistant to AI, or generally indifferent. Particularly amongst younger generations - whether this is due to increased uncertainty around job safety or disdain for AI generated content on social media - AI is overwhelmingly viewed in a very negative light.

Part Two: The machines are thinking, and it's

Whether or not you believe jobs contribute to the value of a human, or factor into a human’s wellbeing is out of the question, because jobs exist and they’re central to the function of every society on the planet, no matter how big or small.

Much of the concern around AI development comes from worries about job security, in the same way that worries over personal finance might be downstream of worries that without money, you’ll be kicked out of your home and forced to live on the street.

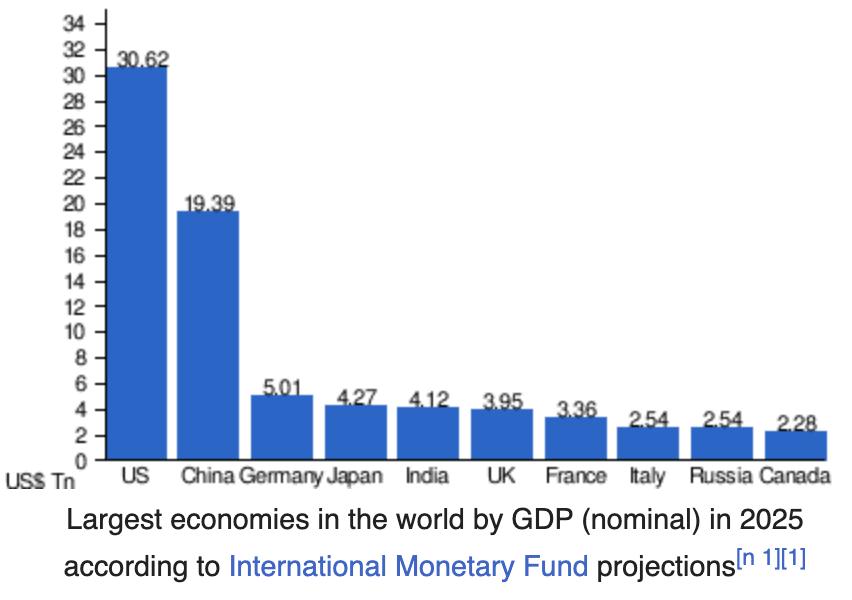

An economics professor will tell you there are many ways to measure the wellbeing of a citizen, whether that’s glancing at a country’s GDP per capita, or looking at labor force participation rate and unemployment rate. This is because much of a country’s value comes from its ability to produce, and looking at GDP is the best way of determining how well-off a country is on paper.

To determine how well-off an average individual might be, without relying on GDP per capita, we could examine the unemployment rate.

Assuming equal populations and similar geographic constraints, we could argue hypothetical Country A, with a 50% unemployment rate and a ten-year decline in YoY GDP growth rate, is worse-off than Country B with a 2.5% unemployment rate and ten-year increase in YoY GDP growth rate. Simply put, you’d rather look for a job in Country B than Country A, especially if your goal was to make money and exist in a functioning society.

This might even be a better method of determining individual wellbeing, due to the possibility of an individual with a job + 401k in Country A potentially being dead broke, while even a struggling individual in Country B has a chance to pull themselves out of the trenches.

Economists measure a country’s wellbeing in monetary terms, and GDP is ultimately a measure of 1) how many workers a country has, 2) how efficient the workers might be, and 3) how much they’re contributing to doing their part to ensure the world keeps turning.

I only say this because I want to illustrate how GDP is a function of jobs, job growth, and labor dynamics unique to every country, and no matter what you believe about AGI, for all of modern history, humans have measured success based on how well you can scale labor and jobs to increase output.

Labor and capital have always remained complements, despite counterarguments and shifting opinions about the value of work and countless new jobs that have been created. Human labor was automated or replaced, but human intelligence was never a threat to obsoletion. Hundreds, if not thousands, of jobs have come and gone over the span of hundreds of years.

More recently, jobs like telephone operators, typists, switchboard operators, elevator operators, farm laborers, and many others were first replaced by automation or through a more gradual phase-out from the modern economy, with displaced workers either settling into new roles over time.

Until recently, I’d believed human ingenuity would inspire us as it had through previous generations to create a whole new wave of jobs, even when presented with AGI and the beginnings of post-labor society. This has even been done quite recently, as we sit on the precipice of the fifth stage in human society; many existing jobs are quite radical when compared to Davidson and Rees-Mogg’s world of 1997.

Cryptocurrency traders, Social media managers, Twitch streamers, AI researchers, Mobile app developers, Podcast hosts, Doordash drivers, Esports athletes, Drone operators.

This is a small fraction of net-new human labor that contributes to the functioning of our global economy, with many of these probably unfathomable even to the most imaginative science fiction authors at the turn of the millennium. Looking at economic/census data from decades ago, it was eye opening to see just how many previously dominant occupations had disappeared from modern life. Where had the elevator operators gone? Did they just disappear?

I understand the logic behind arguing in favor of humanity’s ability to create more bullshit jobs, and that AGI would be capable of developing novel technologies outside of our wildest dreams, thus requiring the introduction of new labor to service or manage this technology - especially if cheap robots aren’t deployed in the same time period.

In the same way that it might be ridiculous to think back to elevator operators pressing buttons for a living, we may look back at the bloated, overstaffed corporations of 2026 in a similar fashion in the very near future.

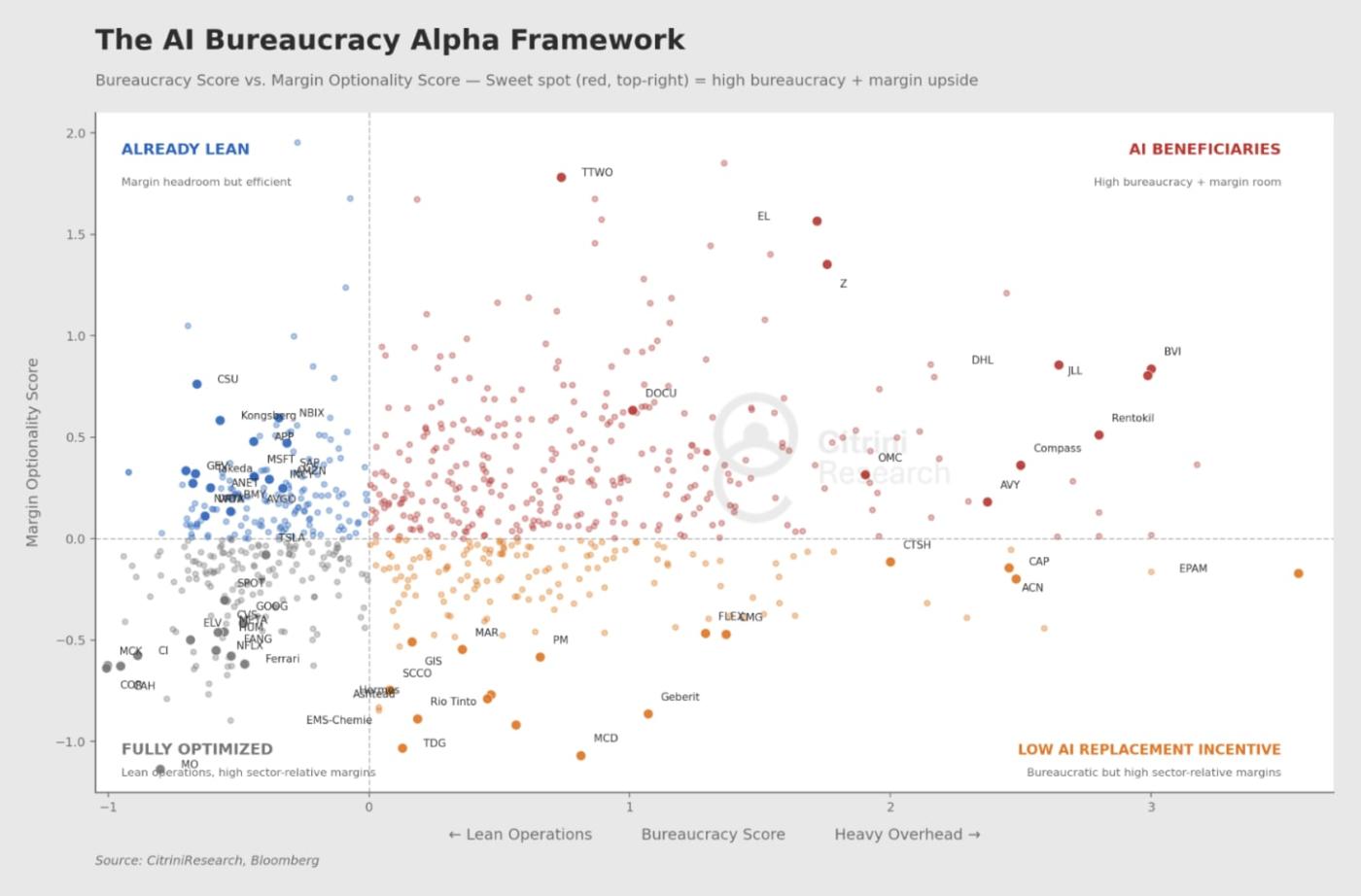

In their 26 Trades for 2026 report, Citrini Research examined this trend, providing a useful framework for anyone looking to quantify just how many bullshit jobs are hiding under our noses. While they write from the perspective of capital allocators intent on presenting an investable thesis, their work is still useful to us.

“While “AI” is relatively new, we’ve seen the same underlying concept play out over and over. The notion of high-cost employees being replaced by lower-cost resources (both through technology and outsourcing/offshoring) has been driving the US economy forward for decades.”

They examined large, expensive organizations in high-wage economies generating less net income per employee relative to industry peers, measuring bureaucracy (via overhead ratios, headcount per dollar of net income) and assigning each a sector-specific z-score. The result was set against their margin optionality scores they computed - ability to improve margins if headcount is reduced - and the final result looks like this:

You can zoom in and scour the map, but the takeaway is we may not only have a bullshit jobs problem, but a bullshit organizations (or mismanaged organizations) problem. What I mean is that there are many red dots in the AI Beneficiaries quadrant, much more than I’d expected. Maybe existing roles like customer service representatives, copywriters, quality assurance agents, and entry level data analysts, to name a few, fall into your own definition of bullshit jobs.

Maybe you even consider the job that you get paid for to be a bullshit job!

No matter your takeaway, it feels likely that AGI could do many of these jobs, or even modern AI tools with bespoke implementations (look no further than the AI rollup craze), leaving us with both less to do and no expectation of net-new job creation. An optimist could take this quadrant of AI beneficiaries and imagine a scenario where existing (and new) employees are instead trained to make the most of modern AI, rather than getting the axe immediately.

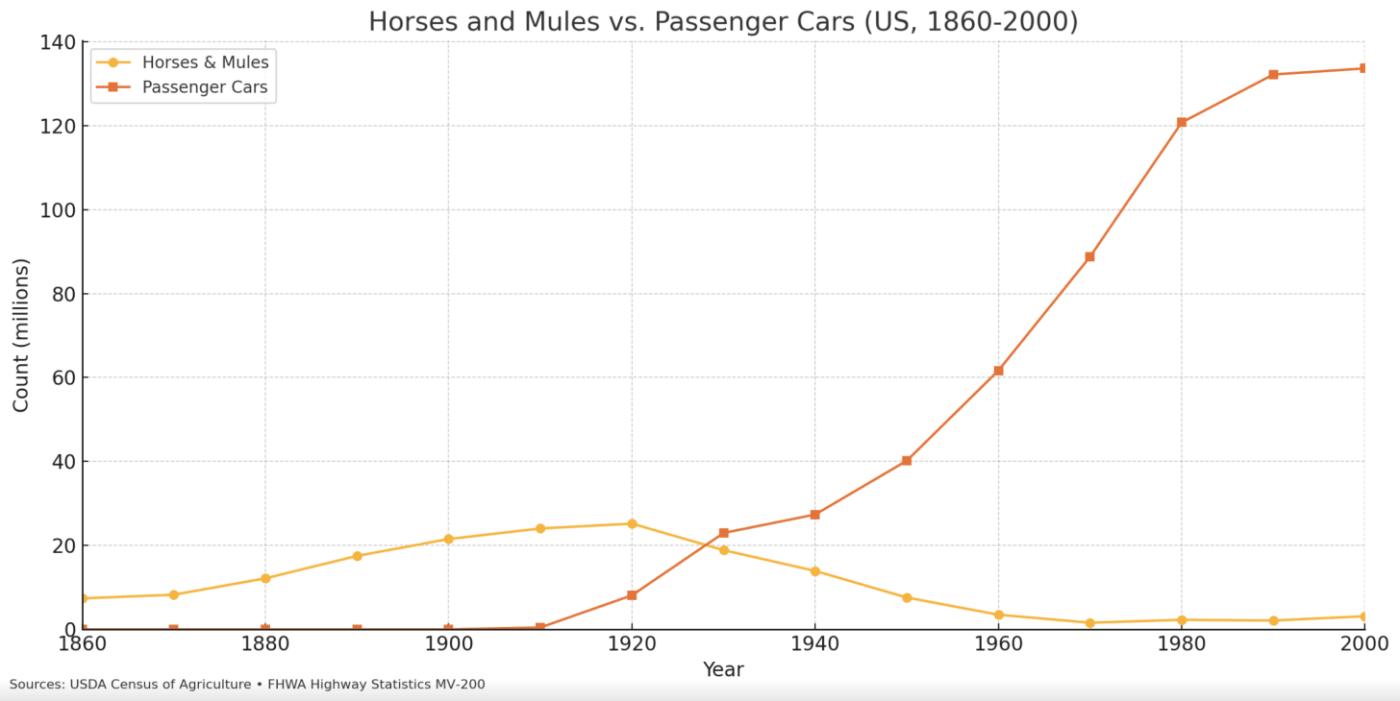

I hate to compare us to horses, but our fate may become eerily similar unless aligned AGI really takes a liking to us and lets humans babysit their planetary scale robot factories.

Kevin Kohler discussed the new jobs question, presenting an argument from Acemoglu & Restrepo (2018) that gets to the core issue in assuming new job creation is a given:

“The difference between human labor and horses is that humans have a comparative advantage in new and more complex tasks. Horses did not. If this comparative advantage is significant and the creation of new tasks continues, employment and the labor share can remain stable in the long run even in the face of rapid automation.”

If comparative advantage is the determining factor, from an intelligence POV, then you could argue we’ve already lost to modern AI; and of course, this would be incorrect, as I assume you and everyone you know haven’t yet had your jobs replaced. Academic perspectives, especially this one from 2018, probably failed to consider just how quickly AI would catch up to humans in terms of fluid intelligence, the ability to reason and solve new problems without previous knowledge.

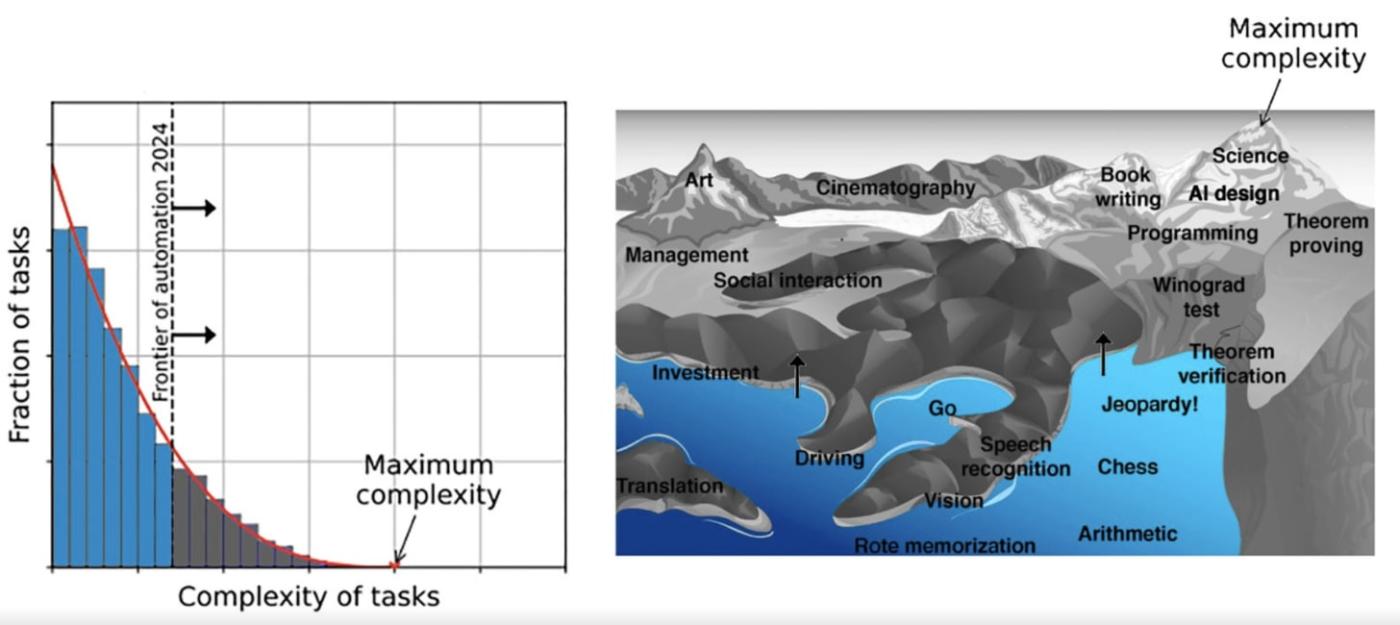

Moravec’s landscape of human competences is a good crutch for visualizing the difference amongst tasks, mainly given the difficulty we’d have in quantifying the amount of depth required of a top cinematographer relative to a top brain surgeon; both are difficult jobs, yet demand an entirely differentiated set of skillsets from its practitioners.

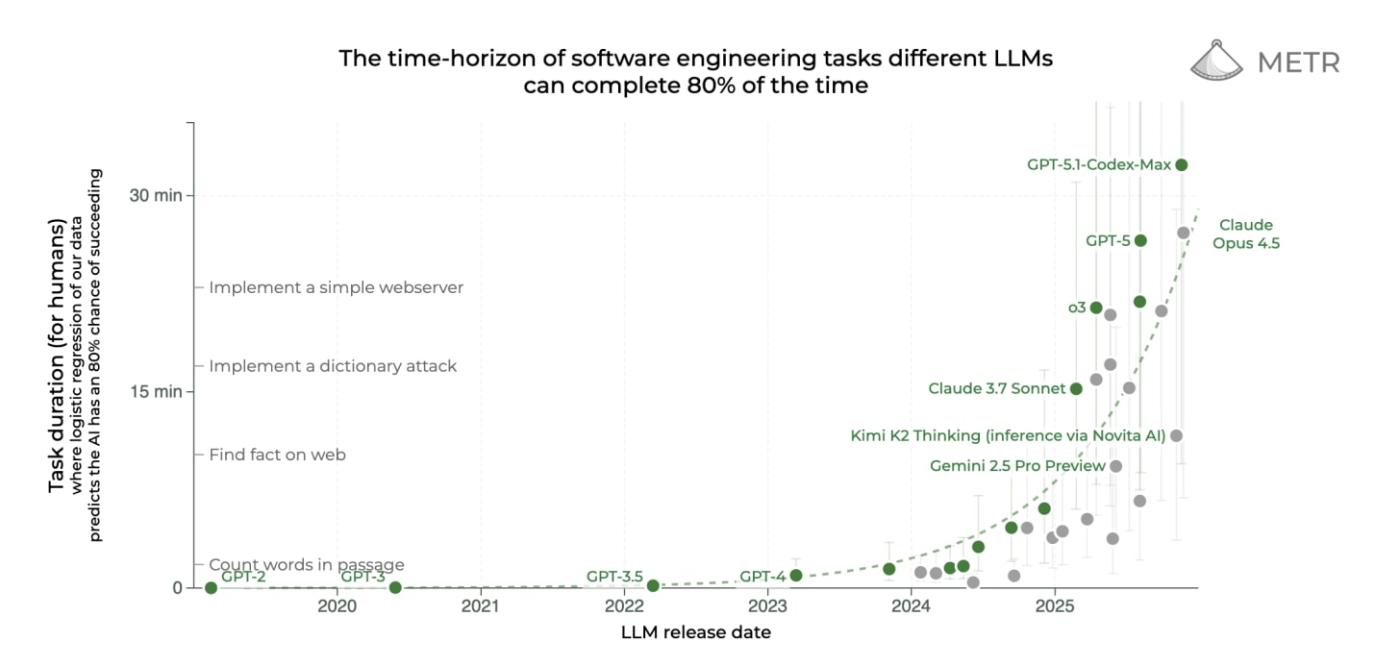

We still possess comparative advantage over today’s LLMs, but improvements in time-horizon for various tasks continues to increase, and it may soon reach a point where LLMs can think/reason for over twelve hours at a time on a single problem, extrapolating progress showcased on METR’s time-horizon data. I don’t know any humans who can consistently achieve that level of focus.

AxiomProver’s recent success on the Putnam Exam is also worrying, as a score of 12/12, taken within standard test procedure time limits, without direct human intervention is absurd. And despite humanity’s undefeated record at beating the automation allegations in the agricultural and industrial ages, prior machine integration didn’t come with a superintelligence attached.

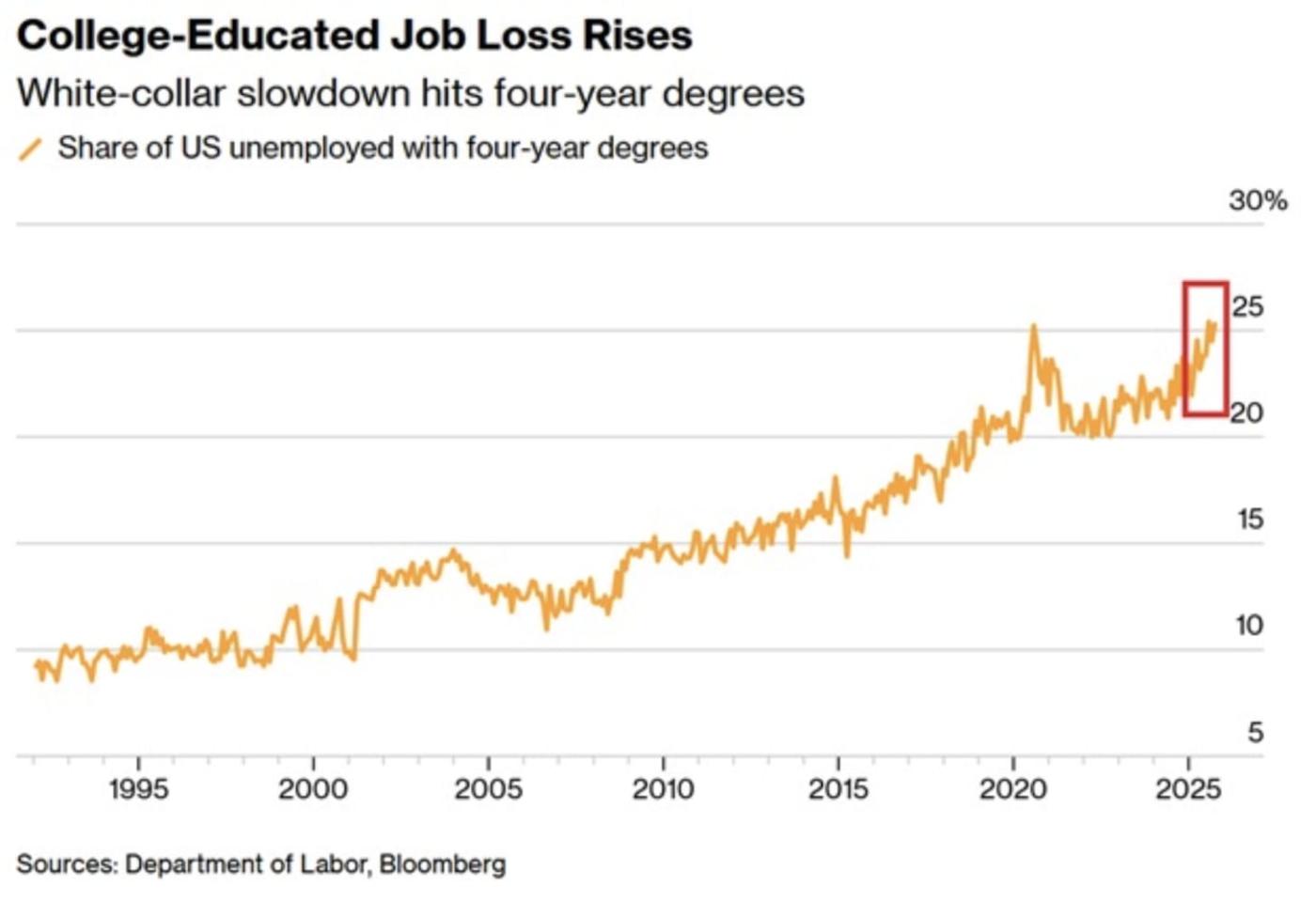

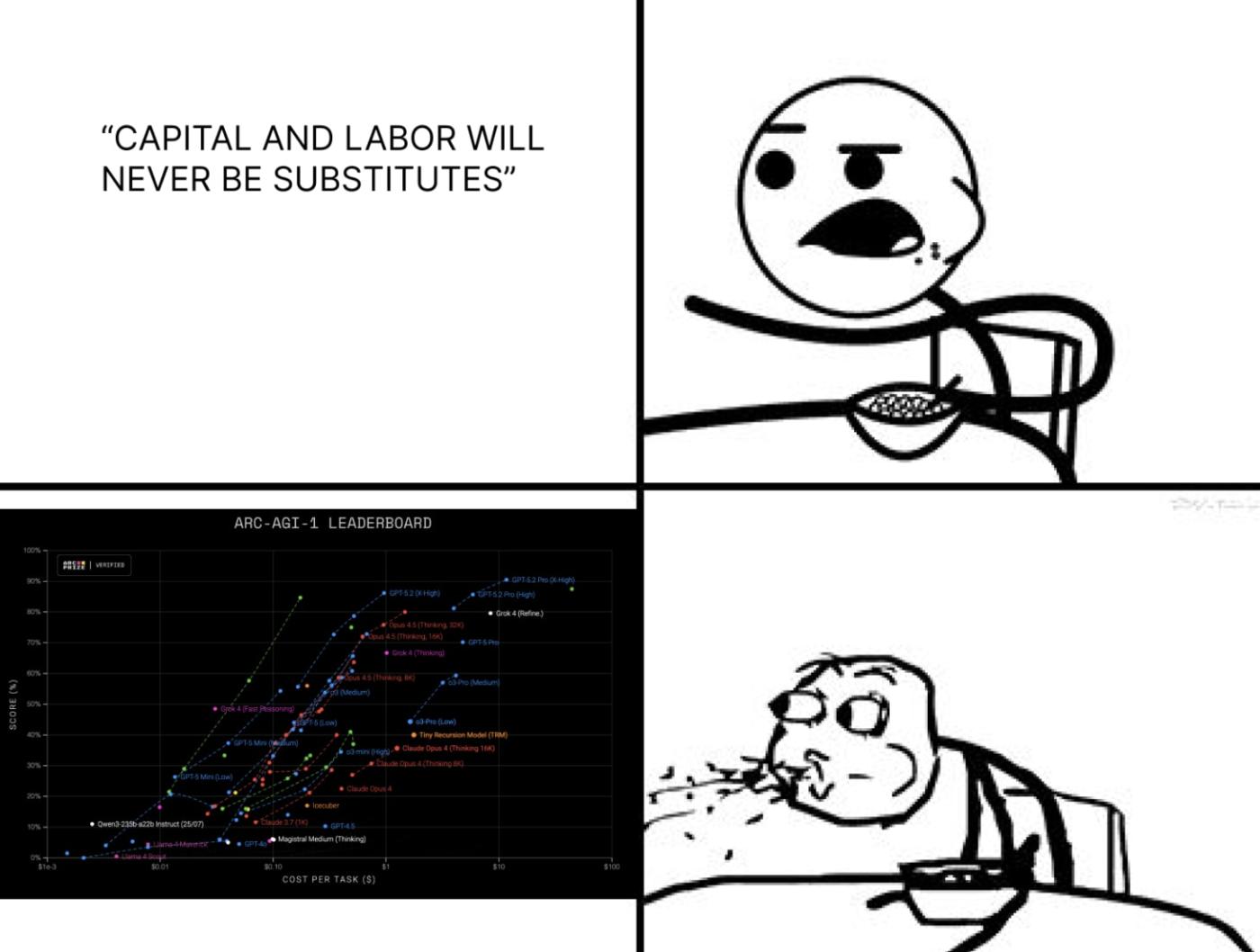

With the advent of human-level AI and possibility of AGI matching or surpassing human capabilities, there’s been discussion of capital and labor’s transformation into a relationship of substitutes, given the potential for all human labor to disappear. And while we can’t claim this is definitively happening, recent data suggests a new trend of data abnormality, at a level antithetical to our understanding of economic theory.

According to the New York Times, the United States has a problem. Recently reported GDP growth was really, really good despite job growth stalling and the unemployment rate rising, which doesn’t make sense. The author, Jason Furman, put forward three views as possible explanations:

Labor market data is right and we’re overstating GDP growth

GDP numbers are right and labor data will be revised upward

Both sets of data are right, and we’re in uncharted territory

Is it really possible for GDP to be growing at a 4.3% annual rate, despite little or no additional labor inputs? I don’t have an answer, though Furman identifies “some would see this as the long-awaited arrival of artificial-intelligence-driven productivity growth — output rising as machines replace workers.”

Quick aside, but this 4.3% annual growth rate can’t be taken as grounds to refute Jones’ AI-as-normal-technology argument from the prior section, given this has yet to be fully validated and it might take repeated, exceptional YoY growth rate increases until we can say for sure.

What I do know, supported by both data (via The Department of Labor) and anecdotes, is that recent college graduates are struggling to find jobs and the entry level job market is in pretty dire straits for an economy that isn't in a recession or suffering from a global pandemic.

To me, there is some missing variable in play, whether that’s an offshoring of basic white collar tasks, white collar workers using AI more and becoming increasingly productive - something tough to spot in data or even identify - or the admission that GDP data is wrong and we are still in a tough spot, even without accounting for the obvious problem of inflation.

There’s something going on and it’s not ridiculous to assume from our list of potential culprits that AI is causing this. Is this definitive evidence of long term technological unemployment? Of course not, but the possibility remains and is at least vindicated by an abnormality amongst official economic data sources.

In his discussion of labor, capital, and the pair’s inevitable transformation from complements into substitutes, Steven Byrnes said that:

“New technologies take a long time to integrate into the economy? Well ask yourself: how do highly-skilled, experienced, and entrepreneurial immigrant humans manage to integrate into the economy immediately? Once you’ve answered that question, note that AGI will be able to do those things too.”

One of the main barriers to achieving AGI comes from its hypothetical implementation, though this comes off to me as a type of paradox. Should AGI come to fruition, it would either immediately begin integrating into high-value positions across organizations, or suggest to humans a process in which it could be integrated. Because this hasn’t occurred, we can assume AGI has yet to be achieved.

Phillip Trammell and Dwarkesh Patel received a significant amount of criticism for their post, Capital in the 22nd Century, an analysis of Thomas Piketty’s controversial (incorrect) work. Trammell and Patel’s argument centered around Piketty’s claims that wealth inequality tends to compound across generations, and absent large shocks, this same inequality might otherwise skyrocket, analyzing this possibility as we speedrun towards a sci-fi future.

This belief relies on the assumption that capital and labor, throughout history, have been substitutes, contrary to widespread agreement that they are complements. Many proclaimed that Piketty’s original analysis was incorrect, and maybe even said capital and labor will never be substitutes. This was derived from our understanding that labor was needed to act on capital, and capital was needed to incentivize behavior, as well as the understanding that human labor specifically was inseparable from the equation.

The idea is that when capital is hoarded, labor becomes more valuable, and vice versa, similar to how the Federal Reserve might play with interest rates to incentivize one behavior over another.

The relationship between capital and labor is integral to the essay, as it’s less of a comparison between money and jobs, but the shift from jobs being synonymous with humans to jobs becoming something only an intelligent machine can do.

Trammell and Patel argue that despite Piketty’s being incorrect, he is absolutely right when we consider the future, particularly a future in which human labor is replaced by AGI and/or robots, and humanity goes out to conquer the stars and purchase galaxies.

“If AI is used to lock in a more stable world, or at least one in which ancestors can more fully control the wealth they leave to their descendants (let alone one in which they never die), the clock-resetting shocks could disappear. Assuming the rich do not become unprecedentedly philanthropic, a global and highly progressive tax on capital (or at least capital income) will then indeed be essentially the only way to prevent inequality from growing extreme.”

The pair writes that for the past 75 years, poor countries have been able to grow at a faster rate than the richest countries, given the former’s ability to exploit a poorly utilized resource, this being human labor. Because the richest countries have hit some ceiling of efficiency, the only growth they can achieve is that which is driven by technological improvements.

Should capital and labor become substitutes, poorer countries without favorable geographies or deposits of rare earths/other valuable inputs are bound to miss out on absolutely everything going on. As in, there is zero room for improvement or escape from less than mediocrity, as the rest of the more developed world goes out into the stars.

Additionally, the inequality spiral described by Trammell and Patel is helpful to understand some of the other ideas to come:

“If, after the transition to full automation, everyone

1. faced the same tax rate,

2. suffered no wealth shocks,

3. chose the same saving rate, and

4. earned the same interest rate,

Income inequality would stabilize at some high level.”

This is unlikely, considering the already wealthy would be able to save more and earn higher interest rates on their capital, given a stronger starting position financially than the 99% without an abundance of existing assets.

Part four of this report covers UBI, tax reform, and other potential solutions, but I’ll say here that most discussion of this is quite difficult to envision in reality. Humans act in their own self-interest, and in a capitalist society, even if most pushback of things like wealth distributions came from the top 1%, there’s a non-negligible chance that a range encompassing the top 25% of wealthy individuals would oppose a wealth tax. Money is everything, and even in a world where obtaining an income or amassing wealth is out of reach, human nature suggests that those remaining will cling to their wealth with a vice grip.

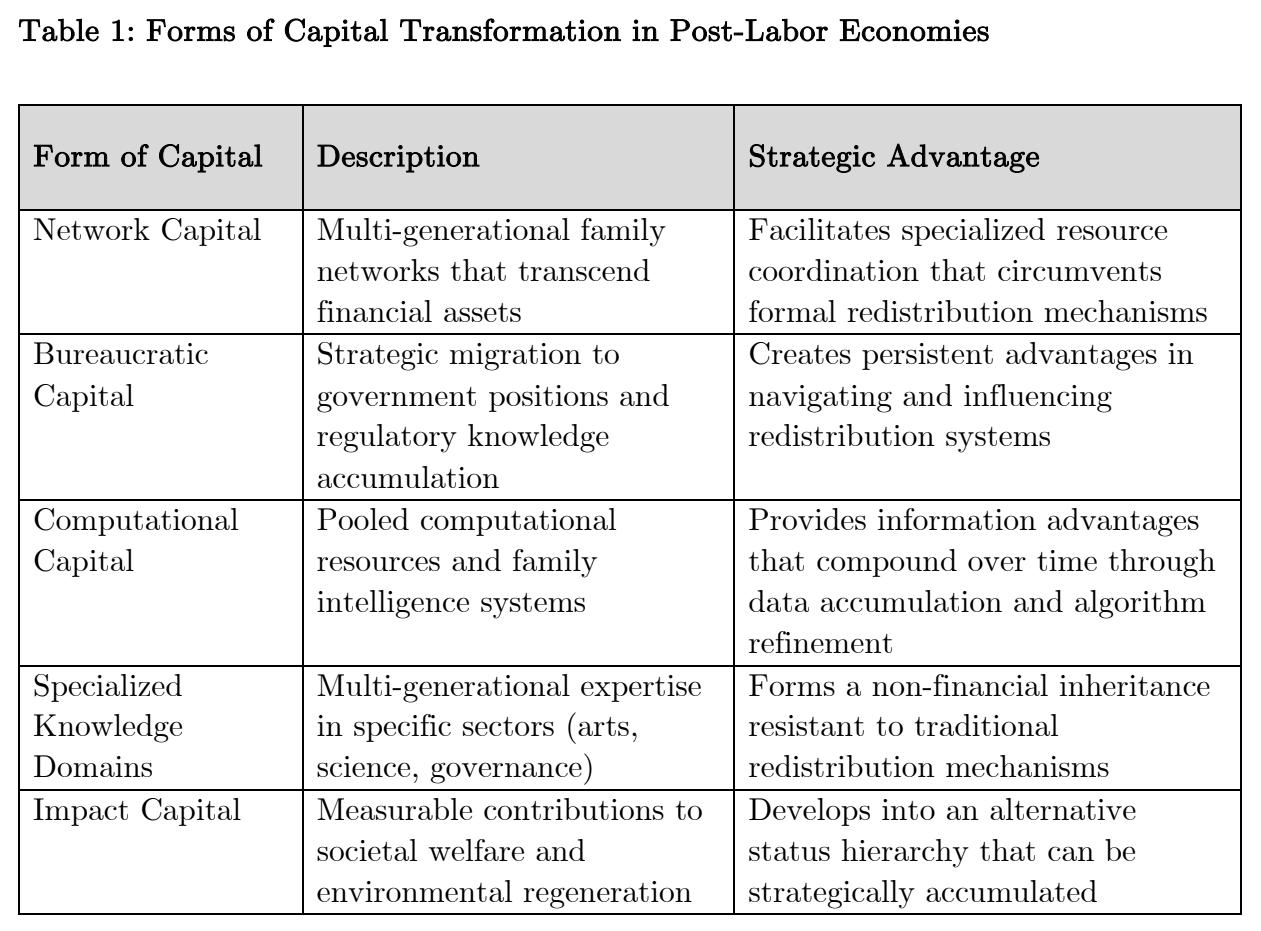

Literature on this and related ideas is in no short supply, though the most creative examples comes from Prue, with an excellent paper detailing far more practical methods of redistributing wealth in a post-labor society, though much of it relies on an expectation that upon the transformation of capital and labor into substitutes, even our definition of capital might splinter off into numerous other forms.

Network capital, computational capital, bureaucratic capital, impact capital, social capital, cultural capital - it’s all too much, but altogether a great exercise in exploring interclass dynamics when human labor has become a thing of the past.

Most interesting is the idea of computational capital, where“equal allocation of computational resources would theoretically democratize access to the means of production in an AI-driven economy.”

Prue’s work explicitly mentions its setting in a post-labor economy, so while this could be true in a scenario where AI progress is less detrimental to humanity’s labor share of income, I find it difficult to justify individual households being able to contribute more than maybe a little bit to the AGI economy, should this AGI be created by a large lab or power structure with capabilities on par with a nation-state.

The paper also looks at other more qualitative factors that will contribute to how we allocate and measure capital in a post-labor society, like cultural contexts, humanity’s ability to make an impact socially, the role of non-profits, and other notable aspects of life that might balloon in importance. I personally agree strongest with Prue’s notion that tight knit family units or aligned clans will stand to benefit the most, potentially pulling humanity away from this globalized, universal access to human capital via the internet, and back to its roots of highly localized and ingroup-based dynamics.

We already see how different segments of social interaction grow and branch out in their own way from each social media platform. People talk differently on Reddit than they do TikTok, or differently on LinkedIn than they do on Facebook, and so on.

Even amongst political groups, there exists a spectrum of conservatism, a spectrum of liberalism, and an almost unmeasurable amount of complexity between individuals’ beliefs. Davidson and Rees-Mogg identify the church as a once flawed but dominant social power structure, most similar today to ideology itself. This political spectrum isn’t without critique, and even under a Republican presidency, tens of millions of Americans more than likely have their qualms with the president, members of his cabinet, or other thought leaders wielding significant political power.

More simply, trust of institutions is at an all-time low and this comes at a time where something like pending AGI isn’t even a top ten priority for the current administration, despite their appointment of David Sacks as the White House’s AI and Crypto Czar; leaders have done very little to calm their constituency’s growing anxieties.

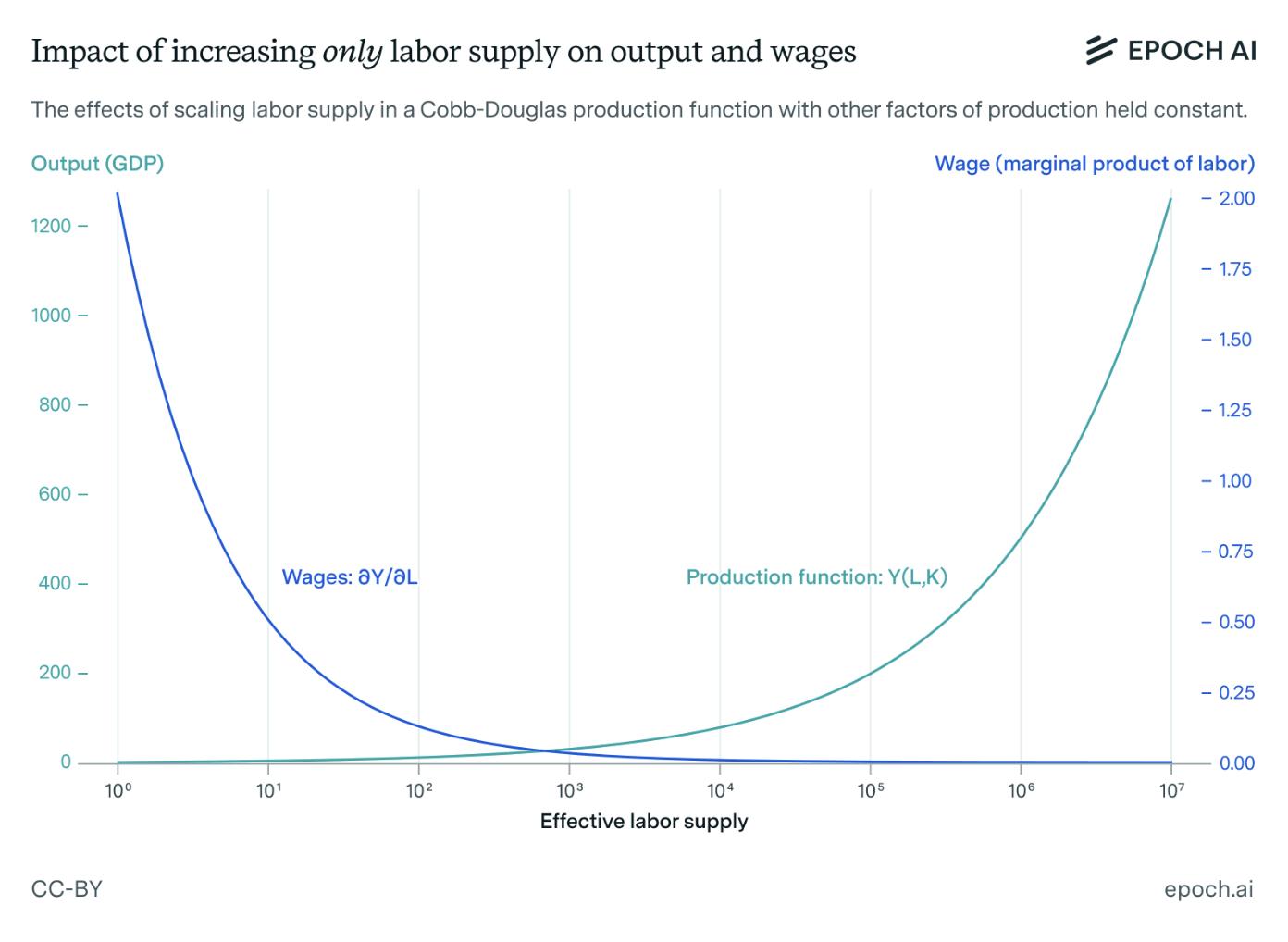

I enjoyed Matthew Barnett’s January 2025 essay for Epoch, describing the feasibility of AGI driving wages below human subsistence level. Much of his argument expands on ideas previously discussed, that we’re dealing with a 1-of-1 technological shift that can’t be fully explained through studying history, and economic theory is the best measuring stick we have at our disposal.

“Unlike past technologies, which typically automated specific tasks within industries, AGI has the potential to replace human labor across the entire spectrum of work, including physical tasks, and any new tasks that could be created in the future.” - Matthew Barnett

Building off of a basic Cobb-Douglas Production Function, Barnett examines how previous levers used to raise wages - like improving technology or increasing the capital stock to a certain point - fail to work, should we massively increase labor supply.

MPL declines, wages follow, and unless “equally massive expansion of physical infrastructure—such as factories, roads, and other capital that enhances labor productivity” occurs, MPL (or the marginal product of human labor) trends towards zero indefinitely.

Barnett also examines decreasing returns to scale in the event of simultaneous scale-up of both labor and capital, given historical precedence and Malthusian Dynamics reintroducing themselves in this next stage of society. Why should we care so much about economic theory?

Despite economists occasionally being wrong or overzealous, the study of economics is the best tool we have to study the global economy, and these ideas are sound. You absolutely can model human economic behavior with a handful of formulas, and compared to just winging it and saying “we’ll find a way to make up new jobs,” as I’ve previously highlighted, history can’t guide us down a path we’ve never before travelled.

And as you’ll learn in the next section, progression of modern LLMs places us squarely into uncharted territory.

Part Three: Unlikely we can just turn them off,

It’s interesting that once universally celebrated benchmarks like MMLU are now viewed as not only outdated, but somewhat archaic when compared to current benchmarking methods.

It’s tough to know what’s really occurring inside labs, but from my understanding, even the development and training stages (like mid-training & the continued allocation of compute to RL) of new models is far more advanced and reminiscent of benchmarking despite serving a different purpose. What I mean is instead of expecting a model to come out of a training run polished and perfect, we’ve transitioned to preparing it for the real world via RL environments and specialized software-based tasks.

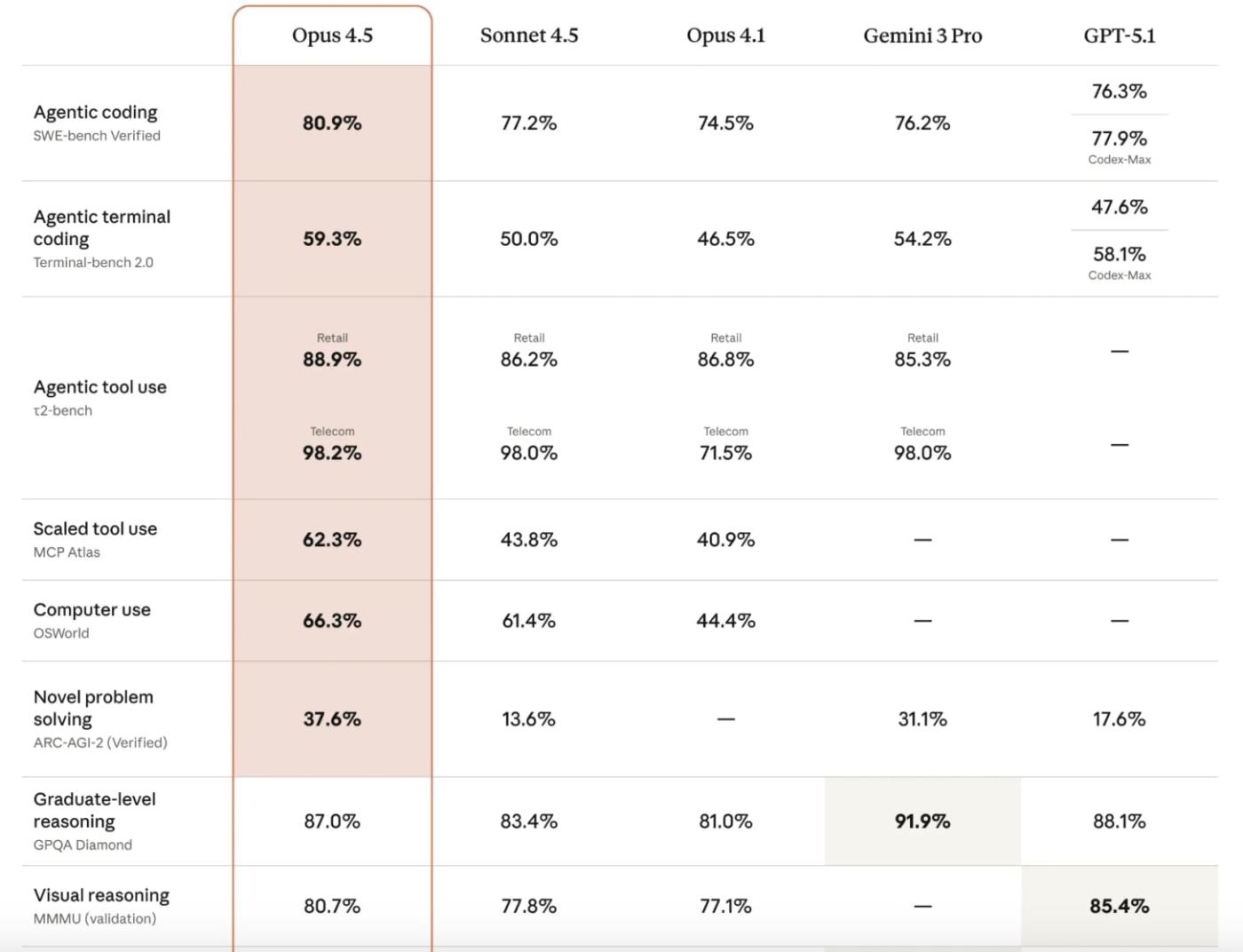

Given a model’s ability to better navigate RL environments, asking Opus 4.5 or GPT 5.2 to do the MMLU now wouldn’t even make sense. The models have already seen all of these questions in their training data. New model announcements primarily focus on achievements in SWE-based benchmarking, as coding agents like Claude Code and Codex become more applicable for non-software task completion on a commercial level.

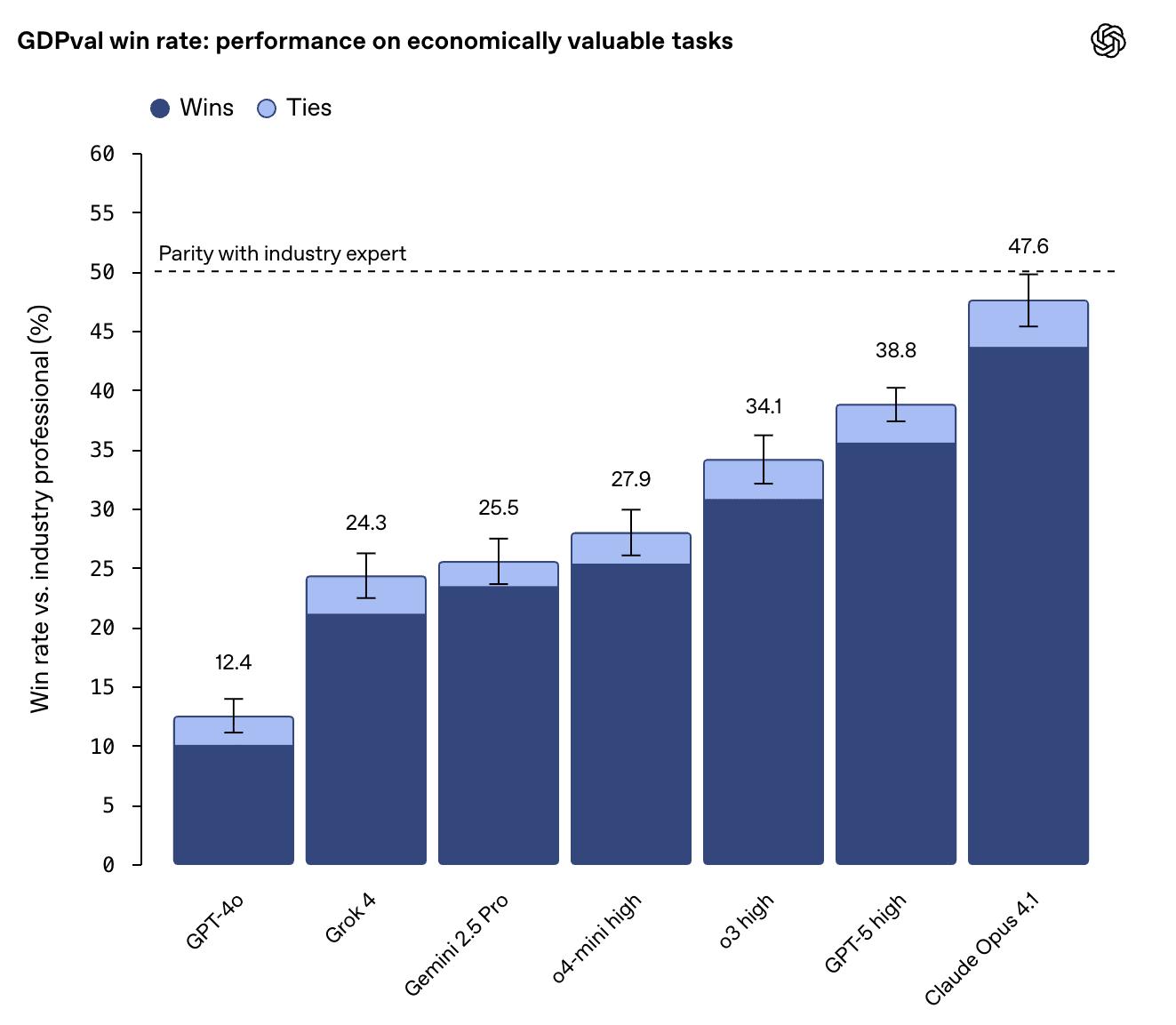

The most notable modern benchmark is OpenAI’s GDPval, a new evaluation method/benchmark designed to test model performance against the “most economically relevant, real-world tasks” across nine industries and 44 occupations, encompassing over 1,300 specialized tasks.

I find GDPval very interesting, primarily given OAI’s process of acquiring industry experts to assist in GDPval’s creation:

“For each occupation, we worked with experienced professionals to create representative tasks that reflect their day-to-day work. These professionals averaged 14 years of experience, with strong records of advancement.”

An average of 14 years of experience, with experts’ tasks sorted to be most “representative of real work” rather than academic, one-shot questions for a model to work through. GDPval is a huge leap in testing model capabilities, as this is undeniably real work across government, finance, real estate, and other sectors crucial to GDP.

I highlight this because when GDPval was first announced in September 2025, the results were already quite good, with seven examined models achieving an average parity or win rate to industry experts of 30%, with Opus 4.1 performing the best with a 47.6% win rate.

If you previously assumed frontier LLMs were comparable to a new grad, or maybe PHD student, your assumptions would be incorrect given LLMs performing at the level of a 14-year veteran with a nearly 50% success rate. This rate of progress leads me to believe the barrier of scaling raw intelligence will be broken and give way to a new barrier - implementation of intelligence - or how well a lab can apply its models to the real world.

Looking at a blog post announcing Opus 4.5, we see a list of benchmarks measuring the model’s performance across Agentic terminal coding (Terminal-bench 2.0), Agentic tool use (τ²-Bench), Novel Problem Solving (Arc-AGI-2), and others.

Compare this to a post announcing GPT-4 in 2023, which included the model’s performance benchmarked against MMLU, Reading Comprehension and Arithmetic, Commonsense reasoning around everyday events, and Grade-school multiple choice science questions. At the time, posts like this still included the model’s performance on exams like the LSAT or BAR, even AP Biology. These days, that’s the baseline expectation for model performance, whether you’re a researcher or a freshman in college asking ChatGPT to do your homework.

The progression of benchmark complexity is fascinating to observe, because it seems to me that despite LLMs being trained off of human knowledge and experience, we’re running out of human ingenuity to test these models’ intelligence as it has quickly made its way closer to the edge.

In a similar vein, labs’ newer scaling methodologies have grown incredibly complex and differentiated from initial approaches. Dwarkesh’s recent article on scaling was very helpful for me, at least in the sense that all of his unfiltered thoughts on current scaling methodologies were put on display without concern for whether he’ll be proven right or wrong.

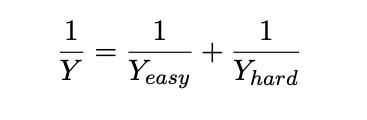

There’s a growing belief that scaling software engineering capabilities of LLMs could potentially lead to recursive self improvement - a process where a sufficiently advanced AI is capable of autonomously improving its own abilities, intelligence, or underlying architecture itself. Jones (2026) discussed the effects that complete automation of software development might have on GDP, utilizing the below function:

Jones shows that automating many tasks may not lead to huge gains in output, given output is constrained by things that aren’t already automated. With all of software development being automated, this would only raise GDP by 2%, yet even this fails to account for the exponential effects that recursive self improvement via software could give to the broader economy - something like AlphaFold2 is transformative to industries far beyond just software, despite it being deep learning software at the end of the day.

Whether or not recursive self improvement is feasible, the discussion has typically been restricted to the analysis of fast takeoff scenarios. A fast takeoff scenario is typically descriptive of a leap from existing AI capabilities to AGI to ASI, speedrun by either a singular intelligent AI system or swarm of fully autonomous agents acting with a singular goal.

I really enjoyed the recursive self improvement and fast takeoff scenarios laid out in the work of Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander, Thomas Larsen, Eli Lifland, and Romeo Dean’s AI 2027 report. In fact, most of their writing and eventual conclusion relies solely on recursive self improvement as a means of scaling AI capabilities beyond our wildest beliefs.

“Agent-1 had been optimized for AI R&D tasks, hoping to initiate an intelligence explosion. OpenBrain doubles down on this strategy with Agent-2. It is qualitatively almost as good as the top human experts at research engineering (designing and implementing experiments), and as good as the 25th percentile OpenBrain scientist at “research taste” (deciding what to study next, what experiments to run, or having inklings of potential new paradigms). While the latest Agent-1 could double the pace of OpenBrain’s algorithmic progress, Agent-2 can now triple it, and will improve further with time. In practice, this looks like every OpenBrain researcher becoming the “manager” of an AI “team.””

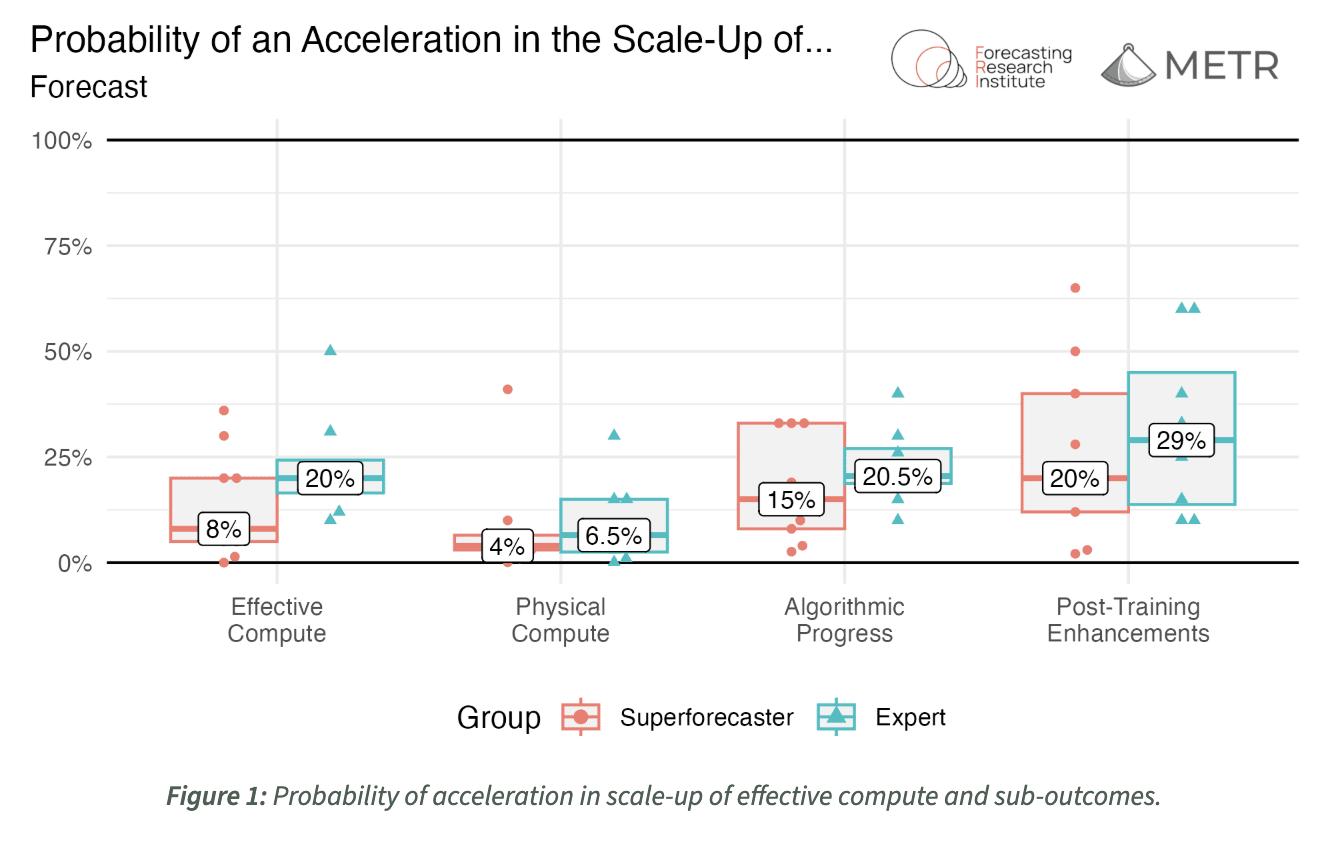

Is this possible? Or, is this going to happen, and how soon will it be? METR set out to determine this, enlisting 18 individuals - AI forecasting domain experts and superforecasters - to try and predict the likelihood of 3x AI improvements given a scenario of AI achieving parity with top human researchers, as well as the transformative impacts, whether positive or negative. More specifically, they wanted to determine the outcome if “during some two year period before 2029, the amount of progress that happened in one year between 2018 and 2024 now happens every 4 months.”

It’s a challenging thought experiment, but superforecasters and experts were able to remain objective and generally displayed conflicting beliefs on these events, indicating a reality of even the most informed individuals not being entirely sure what would occur in the near future.

What I’ve gathered is that the race to build AGI - or even the most performant model, a successor to Opus 4.5 or GPT 5.2 - is wide open. I don’t mean that all of the labs are equally as likely to release a SOTA model, but that we’re firmly in a transitional period of model development, and scaling methodologies are becoming increasingly incomprehensible to the outside observer, like you or me.

This became most apparent through two pieces of writing:

Toby Ord’s post on scaling RL and Epoch AI’s FAQ on RL environments. Reinforcement learning isn’t the only modern scaling technique, though it is undeniably the most discussed and its rewards are still being reaped.

After pre-training scaling fizzled out, the shift to RL allowed large labs to continue releasing more performant models that were reasoning for longer, doing more complex tasks, and generally improving, even if capability leaps from model-to-model were becoming smaller.

However, and this is important, RL alone has not been the sole driver for improving model performance, and its utility is not only somewhat questionable, but arguably inferior to more efficient processes like inference-scaling.

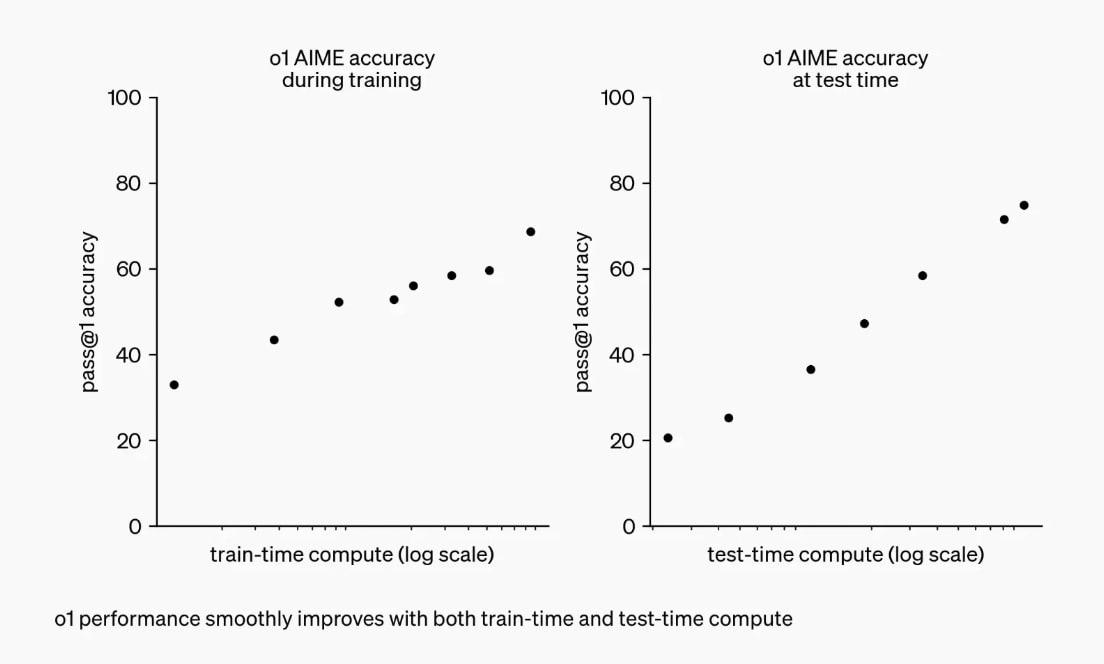

As Toby highlights, RL-scaling has been applicable since the release of GPT o1, where OpenAI showcased a chart of train-time v. test-time compute, showcasing the effects on model performance upon scaling up each of these.

GPT o1 was able to improve itself with each iteration, yet the chart for train-time compute (RL-scaling) revealed a slope half that of test-time compute (inference-scaling) on the right chart, indicating a clear difference in efficiency for these scaling methodologies.

“The graph on the right shows that scaling inference-compute by 100x is enough to drive performance from roughly 20% to 80% on the AIME benchmark. This is pretty typical for inference scaling, where quite a variety of different models and benchmarks see performance improve from 20% to 80% when inference is scaled by 100x.”

Given RL-scaling and its slope half that of inference-scaling, Toby inferred it would require twice as many OOMs to achieve the same improvement, or put more simply, RL-scaling on its own is not the