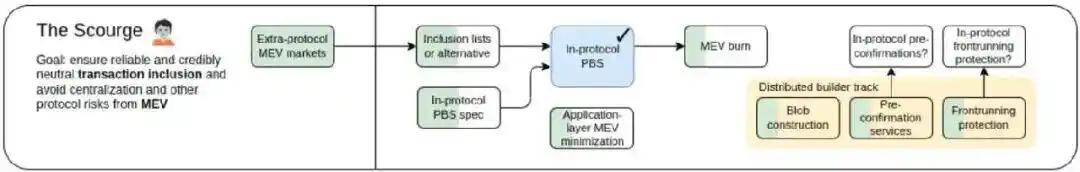

This article delves into the essence of MEV (Maximum Extractable Value) as a structural phenomenon in blockchain, systematically outlining its four-stage evolution on Ethereum and Solana: from chaotic race-up, Flashbots standardization, PBS layered governance, to BuilderNet's decentralized attempt with trusted hardware; it compares and analyzes the institutional differences between Ethereum's open game model and Solana's internalized auction model, pointing out that MEV is essentially a problem of allocating ranking rights, which cannot be eliminated and can only be tamed through transparency, verifiability, and user exit mechanisms.

Article author: Fourteen Jun

Article source: Mars Finance

1. Introduction

Every so often, the blockchain community reignites a major debate about "decentralization": some defend the ideal, some have already dismissed it as a false proposition, and others have long since shifted to a more realistic approach focused on performance, profitability, and regulatory compliance. They've forgotten why they even embarked on this path in the first place.

But I still feel that we haven't really figured out a question: when we talk about "decentralization," what are we actually avoiding? What forces are resisting its move towards centralization, and what logic makes it constantly self-correct?

Over the years, I have observed a particularly ironic trend— so-called decentralized blockchains have gradually given rise to new centralized agents, new power structures, and former challengers have become new vested interest groups, and then dragons.

They are not companies, banks, or governments—they could be miners, MEV searchers, block builders, or even the chain itself.

I chose MEV (Maximum Extractable Value) because, in my opinion, it is the most authentic and naked mirror of this ecosystem.

It pulls blockchain from the pure world of mathematics and cryptography back into the real-world dimensions of game theory, institutional design, and even power politics.

No matter how decentralized a blockchain becomes, as long as there are differentiated powers over transaction ordering and block packaging, MEV will not disappear; it may even intensify and become more covert and systematic.

So I decided to write this article not just to "popularize" MEV, nor just to summarize existing solutions, but to try to go a step further from the perspective of evolution— to use a critical perspective to sort out the structural problems and evolutionary mechanisms behind MEV, and to figure out how it reappears in different roles and institutional forms in every chain and every round of technological upgrades, and continues to occupy the center stage in a different guise.

We all say "code is law," but MEV shows us another side of the reality that "power is law": whoever controls the ordering control controls the distribution of on-chain information, the decision-making power for transaction execution, and even the redistribution of on-chain wealth.

In this article, I would like to start with the following questions:

- Why is MEV not an occasional "arbitrage behavior" but a structural phenomenon?

- How does its role shift as protocol design, consensus mechanism, and on-chain economic structure evolve?

- What exactly have Ethereum's PBS and mev-boost "solved," and what have they left behind?

- How does the design of "high-performance chains" like Solana change the form and participant structure of MEVs?

- Is it truly possible for us to "eliminate MEVs"? Or is our only option to coexist with them and try to tame them?

Only by deeply understanding MEV can we truly understand the underlying institutional logic of blockchain.

This is not only about balancing fairness and efficiency, but also about whether our industry is heading towards becoming a "neoliberal, high-speed financial laboratory" or retaining some kind of idealistic spark of "openness, neutrality, and censorship resistance".

2. Ethereum: From Dark Forest to Layered Game Theory, How Did MEV Evolve?

The term MEV is actually quite misleading, as people might assume that miners extract this value. In reality, MEV on Ethereum is primarily captured by DeFi traders through various structured arbitrage trading strategies, while miners only indirectly profit from these traders' transaction fees.

It's hard to pinpoint exactly when the term "MEV" was invented, but it's certain that it wasn't some unexpected mechanism, but rather a "painful feeling of having to be named."

Back in 2020, Paradigm wrote the now-classic article "Escaping the Dark Forest," comparing the entire on-chain trading environment to a dark forest rife with undercurrents. The suffocating feeling of "you've just finished writing an arbitrage trade and are about to send it out, only to have it snatched up by another bot at a higher price before it's even spread in the mempool" is a fear familiar to anyone who has ventured into the deep waters of DeFi.

If a hacker is foolish enough to directly pursue profit, they will be snapped up by hunters at high prices.

If the hacker is clever, they might use a method similar to the author of this article, employing contracts within contracts (i.e., insider trading) to hide their ultimate profit-making trading logic. Unfortunately, unlike the article "Escaping the Dark Forest" (https://samczsun.com/escaping-the-dark-forest/), which ultimately succeeded, the hacker was still beaten to the punch.

This means that the hunters not only analyzed the parent transactions on the blockchain, but also every single sub-transaction, simulating profit projections. They even went further and examined the deployment logic of the gateway contract, reproducing it exactly, all of which was done automatically within seconds.

Before this, people may have vaguely sensed that on-chain transactions were not equal, but they had not systematically summarized it. The emergence of the term "MEV" gave this structural inequality a clear name for the first time.

The now-defunct "Time Bandit Attack" model existed before Ethereum transitioned to Proof-of-Stake (PoS). If reorganizing a single block yielded extremely high returns, miners could collude to create a higher-yield blockchain to replace the existing ledger. For example, the author of "Escaping the Dark Forest" (https://samczsun.com/escaping-the-dark-forest/) discovered a $9.6 million vulnerability on the chain and ultimately produced a block through privacy transactions. Even with white-hat assistance throughout, their primary concerns, besides transaction leaks and being preempted, were the possibility of malicious miners discovering and forcibly constructing large-scale reorganizations. (Don't underestimate the rarity of reorganizations; when running a BSC node, I observed up to five reorganizations per day even in this supernode mode when block height was insufficient.)

"25,700 ETH Successfully Rescued" (https://samczsun.com/escaping-the-dark-forest/)

This is why MEV has a tense relationship with decentralization.

We initially assumed that blockchain technology was open, transparent, and disintermediation-free, allowing anyone to participate in transactions based solely on rules, not identity. However, the reality is that while you can own an address, you may not have priority in ordering; you can send transactions, but they may not be included in the blockchain before others; you can be an ordinary user, but a certain "Searcher" can always profit from you. This "structurally unfairness" is essentially a "power misalignment": the power of ordering is not in the hands of the user, yet it affects the user's costs and fate.

This misalignment is the starting point for the evolution of the MEV mechanism on Ethereum.

2.1 Phase 1: The Chaotic MEV Free Market (2018–2021)

In the early days of the Ethereum blockchain, MEV was a battlefield without unified rules.

Miners are responsible for packaging transactions, while users can only send transactions hoping to be promptly added to the blockchain. In theory, everyone can compete fairly for blockchain access based on gas fees, but in reality, some people quickly realized that if they could monitor the mempool and immediately copy and pre-package an arbitrage transaction after someone else sends it, they could profit from the arbitrage for free.

This is what is known as "front-running," also called the prelude to a sandwich attack.

At this point, the first active players are the Searchers – like a pack of wolves, they constantly monitor every transaction in the mempool, simulate results, automatically identify arbitrage opportunities, and send their own preemptive transaction packets at extremely high frequency to try to be prioritized by miners.

Miners weren't pushovers either. Initially, they were simply passively collecting higher gas fees, but gradually some miners started bypassing the Searcher altogether, deploying their own MEV bots to participate in arbitrage and circumventing the competition.

Thus, we entered the so-called "miner self-extraction of MEV" stage. Even more extreme, some miners even sell the right to package transactions—openly stating, "I can put your transactions first, as long as you share the profits with me."

The most prominent feature of this period is:

- The ordering rights are not hierarchical; miners, who are both consensus players and ordering players, are also ordering players.

- The MEV market is chaotic; anyone can jump the gun, creating a free market where everyone is vying for dominance.

- Users have no voice; the very act of disclosing their transaction information is a form of deprivation.

Paradigm's "Dark Forest" sparked heated discussions not only because its writing style resembled science fiction, but also because it captured an essential point: blockchain transactions are essentially in a "suspended state of open but unconfirmable information" before a block is generated, and the essence of MEV is to obtain structural profits by utilizing this "deterministic lag".

But this can't go on. Miners are rushing to get ahead, Searchers are harming each other, and users are losing money, causing the user experience of the entire chain to deteriorate.

Thus, the next stage began.

2.2 Phase Two: Flashbots and an Attempt at “Extractable Fairness” (2021–2022)

Flashbots proposed a seemingly illogical but very Ethereum-like solution: since early access is inevitable, why not turn early access into a standardized service?

Thus, the Flashbots Auction system was born—Searchers no longer speculate on the mempool alone, but instead submit their own constructed "transaction bundles" to Flashbots. Flashbots is responsible for organizing multiple bundles into blocks and auctioning them to miners (or later validators). Miners only need to choose which block is the most profitable.

This mechanism solves at least two problems:

- The responsibilities are clearly defined : the Searcher is responsible for proposing profit plans, the Builder (Flashbots) is responsible for organizing transactions, and the miners are responsible for producing blocks. This clear division of responsibilities reduces the incentive for miners to engage in speculative arbitrage.

- User privacy is protected : many transactions no longer enter the public mempool, but instead go through a private channel (Flashbots Protect), preventing them from being preemptively disseminated publicly.

At this point, MEV entered the "mechanized mining" phase. Flashbots became the core infrastructure, through which the vast majority of organized Searchers and Builders participated in block building.

But this does not mean the problem is over.

Because Flashbots is a centralized system, and only transactions that follow its route can avoid being preempted, the issue of "fairness" remains unresolved, only hidden in a different way.

The real turning point came with the "Ethereum merger".

Ethereum merger refers to the upgrade of its consensus mechanism from Proof-of-Work (PoW) to Proof-of-Stake (PoS). The final merger plan was based on the lightweight reuse of Ethereum's pre-merger infrastructure, while the consensus module for block production decisions was separated.

For Proof-of-Stake (PoS), the block time is now every 12 seconds, instead of the previous fluctuation. The block mining reward has been reduced by approximately 90%, from 2 ETH to 0.22 ETH.

This is very important for MEVs for the following two reasons:

- Ethereum's block interval has become more stable. It is no longer the relatively discrete and random situation of 3-30 seconds as before. This has both advantages and disadvantages for MEV. Although the Searcher does not have to rush to send out transactions that are slightly profitable, but can continuously accumulate a better overall sequence of transactions and hand it over to the validators before block production, it also intensifies the competition among Searchers.

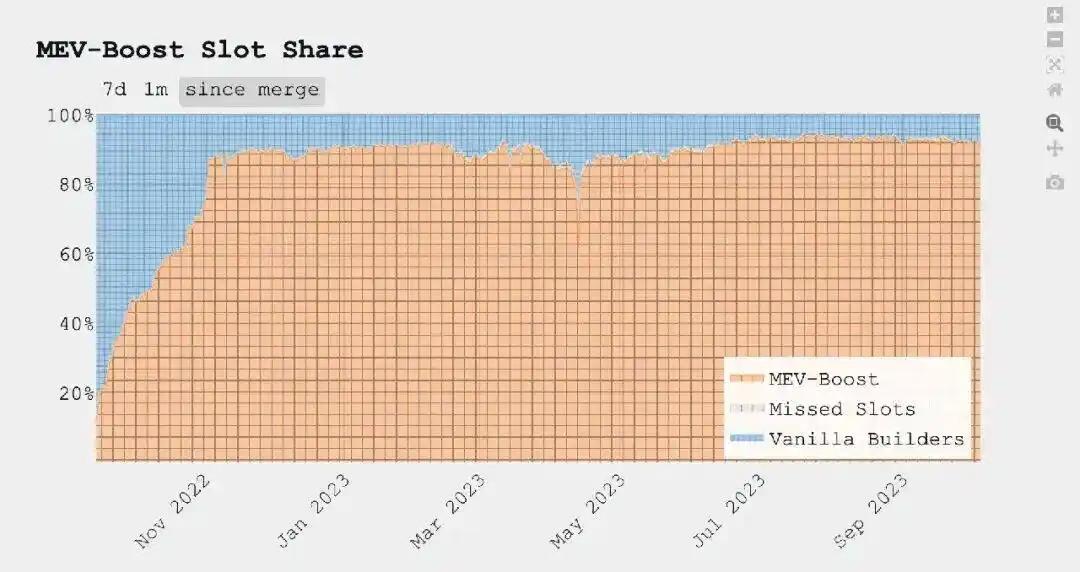

- Reduced miner incentives have made validators more willing to accept MEV trading auctions, allowing MEV to reach a 90% market share in just 2-3 months.

The actual impact is also significant.

- The average profit calculated from MEV-Explore in the year prior to the merger was 22MU/M (starting in September 2021 and ending in September 2022 before the merger; numerical mergers include Arbitrage and Liquidation modes).

- One year after the merger, the average profit calculated from Eigenphi was 8.3 MU/M (from December 2022 to the end of September 2023, the figure includes Arbitrage and Sandwich models).

The final conclusion regarding the change in returns is that, after removing hacking incidents that should not be attributed to MEV from the above data statistics, the overall return rate decreased significantly by 62%. Note that since MEV-Explore's statistics do not actually include sandwich attack data (https://explore.flashbots.net/data-metrics) but do include liquidation returns, the decline might be even greater if only Arbitrage is considered.

So why is that? We need to start with the mechanism after the merger.

2.3 Phase 3: After merging, the separation of blocks brings new complexities (2022–2024)

Flashbots proposed a seemingly illogical but very Ethereum-like solution: since early access is inevitable, why not turn early access into a standardized service?

In 2022, Ethereum completed its historic merger, officially transitioning from PoW to PoS. This was a revolutionary event at the consensus level, and for MEV, it was an "earthquake of structural magnitude."

With the introduction of PoS, block production became predictable (every 12 seconds), the role of miners disappeared and was replaced by Proposers and Validators, and the ordering and block production rights were further separated.

This is the so-called PBS (Proposer-Builder Separation) mechanism.

https://twitter.com/vitalikbuterin/status/1588669782471368704

Flashbots intervened again, launching MEV-Boost—an external module that allows validators to "outsource" block building to third-party Builders, while receiving "build offers" from different Builders through a relay and selecting the optimal solution to produce blocks.

The entire process is as follows:

- A builder creates a block by receiving transactions from users, searchers, or other (private or public) order streams.

- The builder submits the block to the relay (i.e., there are multiple builders).

- The relay verifies the validity of the block and calculates the amount it should pay to the block producer.

- The relay sends the transaction sequence packet and the profit price (also the auction bid) to the block producer of the current slot.

- Block producers evaluate all the bids they receive and select the sequence that yields the highest payout to them.

- The block seller sends this signed title back to the relay (thus completing this round of auction).

- After a block is published, the rewards are distributed to the builder and proposer through transactions within the block and the block reward.

Market share is growing rapidly

[https://mevboost.pics/]

From then on, the lifecycle of MEVs became a "supply chain model." On-chain competition entered an era of "layered specialization":

- Searcher requires volume algorithms and order flow;

- The builder needs to consider volume resources, stability, and simulation speed;

- Relay is a "data messenger" and needs to be neutral and efficient;

- Validator only looks at the quote, minimizing interference and avoiding regulatory pressure.

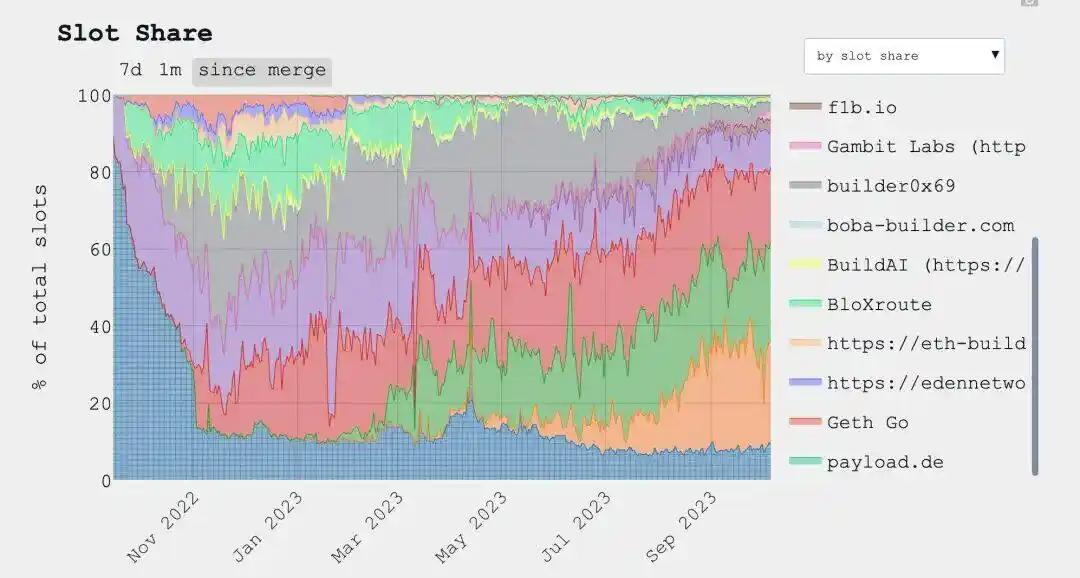

This model is successful in a sense—by the end of 2023, Flashbots held more than 90% of the MEV-Boost market share, forming a de facto "off-chain ranking hub".

But it also brought two new problems:

The first issue is centralization . Flashbots has a very limited number of Builders and Relays. Currently, over 90% of block construction comes from just four Builders, causing what should be a decentralized structure to revert to oligopoly.

"Builder Distribution Trends Involved in Block Production" https://mevboost.pics/

Secondly, there is a lack of incentives . Relays do not inherently charge fees, but they bear the costs of computing, storage, and networking. Several Relay operators, including Blocknative, have announced their exit, and the withdrawal of long-tail participants further exacerbates the risks of centralization.

We can actually understand why this system evolved in this way.

This is not only due to the complexity of building off-chain systems, but also because of the competitiveness of information silos. Faced with the ubiquitous obstruction of MEVs, some have gradually abandoned the AMM mechanism and switched to auction-based bidding protocols, such as UniswapX (which essentially sacrifices the real-time nature of transactions but gains better exchange rates). This allows ordinary users to avoid searching for the best trading path on the client and instead lets professional players fight against MEVs. In addition to professional path deduction and off-chain transaction intention matching, UniswapX also encourages price quoters to build private order flows to reduce competition in MEVs, so as not to grab profitable orders too much and give profits to ordinary users, ultimately reducing the experience gap between DeFi and CeFi.

In this scenario, the private order flow is not entirely private. That is, when Searchers discover a profit delivery trap attack, the Builder can also discover and even steal transactions, constructing a block sequence. However, Builders that constantly steal transactions will eventually lose the ability to receive policy discovery from Searchers (Builders are not unique; overly malicious Builders will be blacklisted by Searchers). Therefore, unless the profit is extremely high, profit sharing will still be implemented to maintain a delicate balance.

In terms of system structure, they can replace each other, and ultimately the order flow will be king. Searchers will want to gradually increase their profit margin, which requires their private order volume to be large enough (so that the profit of the blocks they build is high enough), and thus they gradually become the Builder.

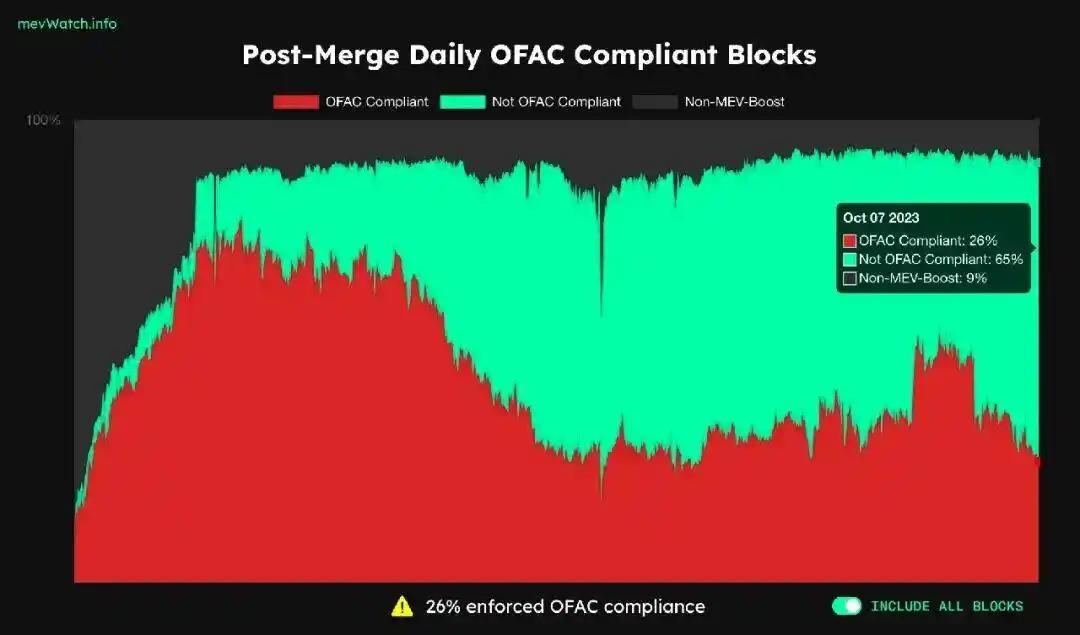

In terms of regulation, they are relatively able to breathe a sigh of relief.

As the cryptocurrency industry matures, regulation is inevitable. All entities registered in the United States and their operators of Ethereum Proof-of-Stake (PoS) validators should comply with OFAC requirements. However, the system mechanism of blockchain dictates that it will not exist only in the United States. As long as there are other relays that comply with local policies, it can be ensured that it can be uploaded and spread on the chain at some point.

Even if over 90% of validators vet relay-routed transactions via MEV, vetted transactions can still be added to the blockchain within an hour. Therefore, anything less than 100% is equivalent to 0%.

"PFAC-compliant Block Distribution Map" https://www.mevwatch.info/

2.4 Phase Four: Decentralized Builders on Trusted Hardware (2024-~)

If the MEV-Boost revolution initially spearheaded by Flashbots was an "open dismantling" of centralized miner power, then the emergence of BuilderNet is an attempt to further decentralize this dismantling itself—to provide a deeper structural response to the question of "who will be the builder."

Since Flashbots launched the BuilderNet project at the end of 2024 , one branch of Ethereum MEV has entered a new phase based on TEE (Trusted Execution Environment) and a decentralized builder network.

From its mechanism, this is not just another product update; it may foreshadow the redistribution of block ranking power in the coming years.

Builder Net is essentially an Ethereum decentralized block building network that runs on TEE and shares MEVs with the community .

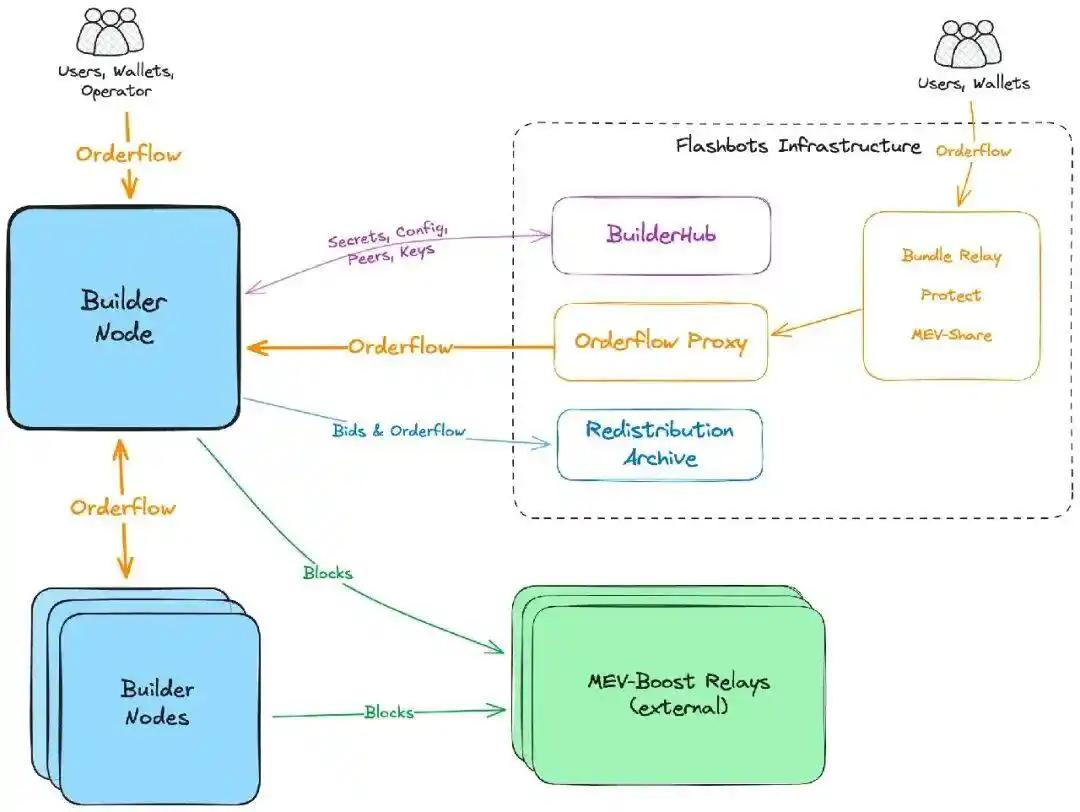

【buildnet Architecture Diagram】

His roles include: Builder node (TEE), Node operator (managing block builders), Flashbots infrastructure, MEV-Boost relay (giving them the final blocks), and Orderflow source (wallet, users, Searcher bot, etc.).

His core concept is multi-operator.

This means that multiple parties can operate the same block generator.

Each operator runs an instance of the [open source generator](https://github.com/flashbots/rbuilder) in a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE), which order flow providers (such as applications, wallets, users, and searchers) can verify and send encrypted order flows to.

Each instance shares the order stream it receives with other instances in the network and submits blocks to the MEV-Boost relay as usual.

After a BuilderNet instance wins a block, a refund will be calculated based on the value added to the block by the order flow provider and distributed to the order flow provider.

This creates an economic closed loop, attracting orders by providing feedback to users.

A detailed explanation of the operating mechanism under TEE

BuilderNet's systematic response to this problem is clear and direct: share the order flow among multiple build nodes running in TEE, build blocks using open-source, verifiable sorting code, and then access the final block production path via mev-boost.

Here's a brief overview of its working logic:

- Each builder node runs on trusted hardware such as Intel SGX or Azure TDX, and external verification mechanisms can be used to confirm that the sorting algorithm it runs has not been tampered with.

- Order flow providers (wallets, DApps, bots, etc.) can send transaction flows to these TEE builders through encrypted channels (HTTPS/TLS) to ensure that their own policies are not leaked.

- All TEE nodes share the order flow within the BuilderNet network, but the information is only readable within the TEE and cannot be spied on by the Builder nodes themselves, ensuring the protection of order flow privacy.

- After the winner block is generated, the system will allocate a refund incentive to the order stream source based on the value of the block, and users or wallets can receive the subsidy.

In other words, BuilderNet "depersonalizes" the builder—nodes are not companies or exchanges, but verifiable instances of sorting algorithms.

BuilderNet is highly similar in concept to the previous Flashbots MEV-Share. It can be said that BuilderNet is a "trusted hardware evolution of MEV-Share".

Through TEE and multi-node collaboration mechanisms, BuilderNet makes a more thorough attempt at structural decentralization regarding the original issue of ordering. It does not trust any single organization or server, but instead lets the code and hardware assume the role of trust.

From an adoption perspective, BuilderNet's current market share on the Ethereum mainnet remains limited; according to Dune data, it has only built a small number of blocks. However, this is not surprising.

- The build process is slower, and the TEE execution environment has a performance bottleneck compared to running in the native kernel;

- Sharing order flow across multiple nodes increases communication load and poses significant challenges to real-time performance.

- Users and wallets have not yet widely integrated their order flow channels (although cashback addresses are open source and operational).

But importantly, its system logic loop has been established , and every component (node registration, remote proof, order flow encryption, block auction, refund calculation) is open source and deployable.

A prototype of a "decentralized builder network" has been realized.

summary

Is MEV revenue really declining?

According to EigenPhi data, in the year following the Ethereum merger, the average profit of MEV was approximately 8.3 MU/M, compared to 22 MU/M in the year before the merger, representing a drop of 62%.

Does this indicate that MEVs are "receding"?

I believe that's not entirely true.

This is more like a case of "the weaker party in a game": in the early stages, due to the chaotic mechanism, low arbitrage threshold, and frequent preemptive moves, Searcher's profits were unrealistically high.

After the merger, the mechanism became more transparent, the ranking system became more hierarchical, and the competition became more intense. Profits were spread across multiple roles in the entire chain, which also stemmed from the intense competition upstream, causing profits to shift to the back end of the chain.

In other words, MEVs haven't disappeared; the "revenue chain" has simply become longer and shifted. In this process, users actually receive a degree of fairness.

As things stand, the problem of extreme market concentration in the builder market is actually more severe.

Over the past 30 days, the top five builders have built more than 80% of Ethereum blocks, and one of the root causes is the monopoly of order flow : large builders control the source of high-quality order flow and, through exclusive protocols or preprocessing capabilities, enable themselves to always provide higher-value block packages.

This is a dangerous centralized flywheel—the more it's built, the more the order flow tends to concentrate, leading to even more builds.

Because miners are the ones who ultimately produce blocks, they are the most capable of extracting mevs themselves. On the other hand, after a Searcher makes a bid, it also faces execution risks, limitations in the expressive capabilities of Ethereum's native transaction types, and concerns about miners preemptively executing its own strategies.

Because of this mutual skepticism and concern, miners and searchers have integrated with each other. Miners can increase their share of MEV by making customized deals with searchers and outsourcing the search for MEV opportunities to them, while searchers can better control the order of transactions by building relationships with miners they trust.

This will lead to a concentration of power in the hands of the most unethical participants, while simultaneously reducing network enforcement and user protection.

Looking back at the evolution of Ethereum's MEV, it is essentially a modernization process that has evolved from "natural early adoption" to "institutional stratification".

The earliest MEVs were like primitive jungles, relying on robbery, speed, and burning money;

Later came the contract society, which established order through Flashbots, but also brought about centralization;

After the merger, a stratified society was formed, with different roles fulfilling their respective responsibilities. However, inequality still existed, only in a more logical way.

This is like an evolution of social governance:

- From chaos and violence (primitive preemptive strike)

- To the black box agreement (early Flashbots).

- Then there's the constitutional separation of powers (PBS framework).

- However, power remains concentrated and elite rule still exists (a few Builders and Relays monopolize power).

One of the prototypes for the next stage is BuilderNet, which represents a reconstruction of the role of the "builder" itself and is also the most structurally sound sorting system design.

It is neither absolute idealism nor complete cynicism, but a "realist governance order" that is very similar to "blockchain-style democracy": there is freedom, but it must be earned through strength.

There is competition, but it's still better than chaos.

III. Another structural solution: Solana's auction pre-processing and high-speed blockchain scenarios

Beyond Ethereum's "open market + module role game" model, MEV has another model. Instead of building a multi-role relay network, it places the auction in advance and incorporates it into the client protocol stack kernel , attempting to complete transaction sorting and profit distribution at the chain level.

The most representative example of this "centralized path" is Solana and its core MEV infrastructure: **Jito**.

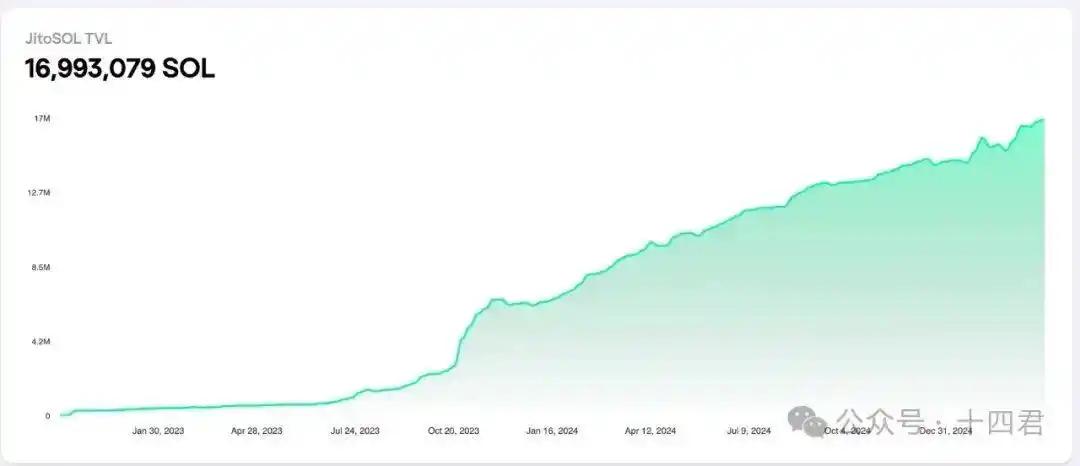

Let's take a look at the amazing speed of his market share growth using a timeline, and pay attention to the pledge ratio and related partners.

- Established at the end of 2021

- Launched on the Solana mainnet in June 2022, it already had 200 validators by September of the same year, covering 15% of the staked amount.

- From 2022 to 2023, through financing, iterations, and a collaboration with the Solana Foundation, the Jito client was included in the official recommendations.

- In 2023, TGE pledged Jito to obtain MEV yield bonuses, forming a pledge-re-pledge model.

- In Q1 of 2024, due to strong community opposition, the channel for jito-solana to send transactions to jito-blockengine was closed.

- In Q2 of 2024, we partnered with over 500 validators, covering 70% of Solana's MEV (Mean Estimated Transaction Values), and processed 3 billion transactions throughout 2024.

- In Q1 of 2025, the staking coverage ratio reached 94.71%. Today, the importance of cross-chain bridges remains self-evident.

Based on the amount of staking, Jito can be considered the leader in the infrastructure of the MEV ecosystem on Solana today, which has been developing over the past 3 years.

A robust support base of Solana validators was established, ensuring that the vast majority of transactions passed through Jito's system.

It was his system offloading that significantly reduced Solana's downtime.

He was the one who enabled the clippers to achieve high profits.

He also enabled Solana's validators to gain an additional 30% MEV reward, and it was a steady increase.

It was he who transformed from the initial dragon-slaying hero into the dragon himself, repeatedly switching between hero and dragon, sometimes ferocious, sometimes kind.

In today's mainstream meme narratives, it has become a versatile force that appeals to both mainstream audiences.

In the past year, he initiated a total of 4.3 billion bundles, generating a total of 5.51 million SOLs in tips fees. At a market price of 140, this would generate an additional $7.7 billion in revenue for the jito infrastructure.

3.1 MEV Auction and Block Generation Process on Solana

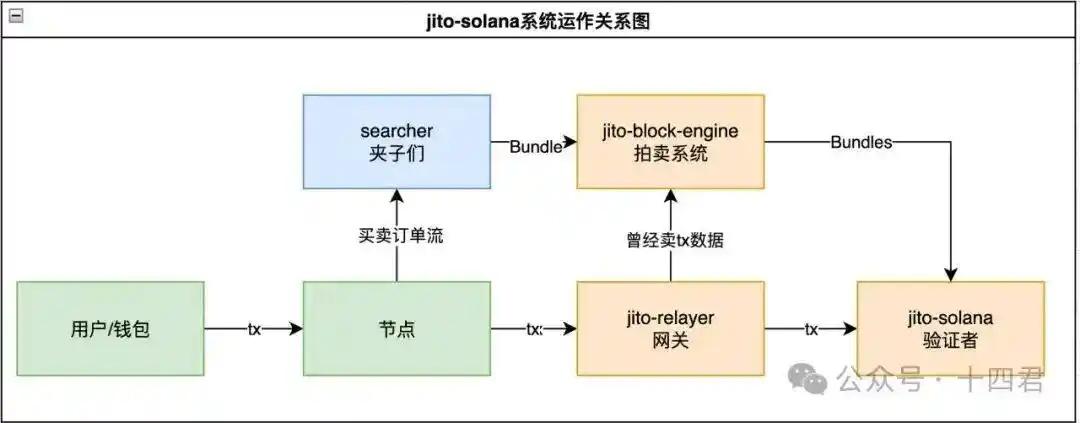

Jito's architecture can be divided into three parts:

- Block Engine: Responsible for the auction logic of MEV Bundle, allowing the Searcher to participate in the auction by submitting Bundle packages (a combination of multiple transactions), and attaching Tips to validators to achieve ranking priority.

- Jito-Solana Client: This is a custom validator client for Jito, integrating native support for the Block Engine. Validators running this client can prioritize auctioned bundles, skipping the regular transaction queue.

- Jito Relayer is a transaction sending and receiving hub. Early on, it was exposed for prematurely leaking transaction streams to the Block Engine and even others through a 200ms delay mechanism, essentially a private mempool fee mechanism. Now, there's an official statement that it will no longer sell transactions.

This system is not just for MEVs; objectively speaking, it serves all scenarios that require acceleration and bulk transaction integration.

For example, the lively opening events on Solana are actually the result of market manipulators using the bundling and acceleration mechanisms to open the market and deploy chips.

For example, major exchanges can also prevent attacks by bundling tips with users' large transactions. However, it's important to note that these methods cannot prevent validators from acting maliciously (in fact, you can't determine which validator is committing the malicious act).

This stems from Solana's unique chain mechanism.

Solana is a blockchain designed for high speed. It does not have a traditional public mempool ; transactions are broadcast directly to the next block producer (leader) through peer nodes. Its structural characteristics are as follows:

The most unique aspect here is the absence of a memory pool. However, Solana doesn't have a memory pool; it only reduces public data transfers, rather than completely eliminating (and impossible to eliminate) them. This characteristic makes the Searcher on Solana a tool exclusive to advanced users.

Secondly, there is also a prediction mechanism.

Validators will be randomly sampled from 1300 validators every epoch (approximately 2-3 days). The VDF algorithm is used here, and there will be a weighting effect of staking.

For example, if the total amount of SOL staked is 2 million, and you stake 200,000 SOL, then you will have a 10% chance of being selected in each random draw.

If selected, the block is generated in approximately 1.6 seconds for the next 4 slots (a concept of block representation in Solana).

This speed is so fast that any valid node can calculate who the next validator is and try to connect with him and submit the user's transaction. Due to network latency, it is also easy for the transaction to miss the current leader and be sent to the next leader instead.

Why are MEVs harder to manage on Solana?

These mechanisms all seem designed to make it less likely for users to get pinched, so why are pinches most rampant on Solana? The key reason lies in other factors.

It's difficult to definitively prove that the leader committed wrongdoing. There are two leaders, A and B, who can all obtain all user transactions, so the cost and ambiguity of leader B committing wrongdoing are reduced.

Imagine I'm the second leader, and I see a profitable deal. So I quickly create a trap attack and submit it to Blockengine for auction. Under the 80% Bundle priority mechanism, my attack will naturally take effect first, but the one packaged is leader A.

So how do you determine that I, leader B, am the attacker?

And why are Solana validators prone to defection?

Because the profits are so high, and the costs are also very high, it forces validators to constantly expand their sources of income and increase revenue.

The validator's annual voting cost is approximately 300-350 SOL (estimated at $42,000 based on a market price of $140) and hardware cost is $4,200 (not including the cost of the dynamic network).

Solana's huge node configuration burden requires nodes to have at least 24 cores, 256GB of memory, and 2 x 1.9TB NVMe modules.

The most common customized Latitude models on the market are currently used by 14% of validators, and they cost $350 per month.

Ultimately, this resulted in only 458 of Solana's 1,323 validators being profitable. This is why the " SIMD-0228 proposal " failed to pass the vote.

In conclusion, this proposal will further reduce block production incentives, inevitably forcing smaller validators to exit, and potentially leading to an irreversible shift towards platform centralization. Furthermore, what do you think will happen when the rewards for mevs increase while the rewards for core work decrease?

3.2 How to understand Jito's merits and demerits in Solana

This is my view: a truly good market will constantly attract new competitors, while an oligopolistic market will stifle challengers. And what kind of market does the platform aspire to be?

Jito's oligopoly, which is also a side effect of Solana's high-speed structure, effectively transfers the opportunity for fair on-chain competition to a small number of participants who have data and block-producing rights.

Jito was once the "dragon slayer" that solved Solana's downtime problem, but as its client monopoly and data privileges gradually solidified, Jito gradually became the representative of "becoming the dragon".

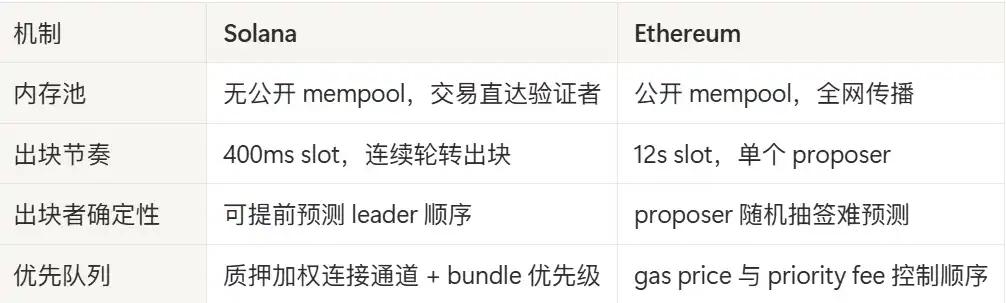

By comparing the core tokens, it can be said that Ethereum is an open, multi-player game-themed MEV market; while Solana is more like a closed-loop order system with a dominant platform for unified management.

What we are seeing today is no longer just a contest of different MEV tools or tactics, but a fundamental divergence in institutional design:

- Ethereum has chosen an open game market logic, where each participant has the right to participate and the exit mechanism;

- Solana opted for a centralized model that prioritizes platform internalization and packaging efficiency, while also focusing on system stability and throughput.

Solana has successfully achieved "extreme throughput + extreme sorting control", but at the cost of compressing the on-chain game space.

However, I believe that performance issues can ultimately be resolved.

Any company can long node global optimization. Ultimately, the company can establish the fastest SMS channel based on the continent where the leader is located, ensuring that its transactions reach the leader quickly. It can also establish a multicast strategy to distribute different user needs. The future competitive outcome will inevitably be the result of refined operations.

However, the problem of market competition crowding out businesses cannot be solved.

If Jito-Solaana leverages its oligopoly advantage and modifies its Bundle priority strategy from 80% to 90%, or even 95%, then ordinary users will have no choice but to endlessly increase Priority Fees to compete for the remaining 5% of CU space.

So why is the market competition for ETH more open, while the competition for Solana is more exclusive?

In my opinion, the root cause is the lack of a Builder bidding role.

In Ethereum, multiple Builders can produce multiple final block sequences, and the validators simply verify and select which one to use.

However, Solana only has multiple block engines (and each one is its own), and the transaction queue it provides to validators is actually a single bundle (5 transactions), which eliminates the competition among multiple builders.

Objectively speaking, looking at the history of ETH, there is no absolute fairness. This competition will significantly increase the rewards of validators and reduce the rewards of searchers. When the rewards of searchers decrease, the possibility of attacks will also decrease, eventually reaching a balance.

IV. The Shadow of Freedom

So far, we have seen MEV evolve from Ethereum's "decentralized game mechanism" to Solana's "platform-built-in auction distribution logic." Although the two paths differ greatly in their technical solutions, they both point to the same core problem:

Who controls the ordering?

The control over the ordering power is not a "technical detail" or "optimization item," but rather the deepest institutional foundation of blockchain: the protection and breaking of decentralized power structures.

4.1 Vitalik's Reflection: Was the MEV a Design Failure or Inevitable?

In his 2024 article, "Futures yet to be decided," Vitalik offered a highly philosophical reflection:

“MEV is not a bug, but a natural byproduct of a system’s power structure. Blockchain either explicitly grants ranking rights or implicitly generates ranking advantages… In the absence of a coordination mechanism, ranking advantages often evolve into opaque operations and rent-seeking structures.”

In other words, blockchain can never completely eliminate the right to order; at most, it can only determine who controls it, whether it can be verified, and whether one can exit it.

Today's MEV designs, whether it's Ethereum's MEV-Boost architecture, Solana's Jito auction, or other chains' private relay mechanisms, are essentially answering three questions:

- Who has the right to determine the order of priority?

- Is the sorting behavior transparent and verifiable?

- Does the user have an opt-out or self-selection mechanism?

4.2 Is MEV a poison for decentralization or a catalyst for evolution?

Many view MEV as a cancer on blockchain systems, while others believe it's a natural outcome of market-driven evolution. We can examine it from two perspectives:

Positive aspect: MEV incentive mechanism improves efficiency

- Validators have a stronger incentive to keep their nodes running because they can earn additional revenue through ranking fees.

- The Searcher introduces more sophisticated and intelligent arbitrage behavior, improving price efficiency in the DeFi market;

- Ranking auctions offer programmability and fund allocation mechanisms, and have even spawned new scenarios such as cross-chain arbitrage and NFT liquidation.

This is an approach that "acknowledges the existence of ranking rights but then handles them through market mechanisms ."

Negative perspective: MEV is a centralized, invisible corridor.

- The ordering power is transferred to non-consensus entities such as relays, builders, and client operators, resulting in the governance structure being bypassed;

- The information gap between the data providers is widening, and ordinary users are becoming the "data harvesters."

- Chain-level security models are increasingly relying on closed-source components, which violates the original intention of transparency and verifiability.

Jito's "client-integrated sorting logic" approach has both improved efficiency and, conversely, bypassed governance and community consensus, creating a de facto sorting oligopoly.

Both have their strengths and weaknesses. Without positive modules, validators themselves may find it difficult to survive. Without negative modules, profit-making entities (attackers) lack room to grow. Together, they form an ecosystem that evolves through a constant game of survival.

This has led to a more dynamic system.

Vitalik mentioned

“Trying to eliminate MEV entirely is futile. The best we can do is to make it transparent, fair, and optionally avoidable.”

In other words, MEV cannot be "eliminated"; it is a side effect of the system's openness and programmability. What we should really be thinking about is "allowing it to operate in a more transparent, open, and equitable manner."

The struggle over MEV is actually both a manifestation of economic freedom and an outlet for the centralization of power.

Just as the early internet claimed to "decentralize the world," it ultimately gave rise to super platforms like Google and Meta. The commodification of ranking power will eventually attract resources, capital, and authority to specific nodes.

Without intervention from chain-level governance and structural mechanisms, MEV will accelerate the formation of a "protocol oligopoly"—client providers, relay networks, and builder alliances will gradually control the "fate" of user transactions.

This is not a matter of who designed it better, but rather a natural consequence of the institutional prototype and incentive path.

4.3 The Next MEV Phase

The past decade of MEV has been an evolution of ranking rights. From miners' private mempools to Flashbots' builder network, and then to Jito's on-chain auction system, MEV has constantly changed its form and spawned new roles, but it has never disappeared; it has only become more sophisticated, institutionalized, and covert.

The future ranking market will evolve into an interchain mev market , where the main chain is merely a settlement layer. Ranking and priority selection will occur on a decentralized, cross-ecosystem ranking protocol, ushering in a "monetization era" of a freely floating market.

Privacy has become a prerequisite for the design of new systems, no longer just about "data protection." "Privacy is not about hiding information, but about balancing power." This has disruptive significance for the MEV world.

In the current architecture, premature exposure of information (such as exposing the mempool) is a major incentive for MEVs . Therefore, many solutions aim to prevent pre-insertion of clips by "encrypting the mempool." Suave, Fair ordering, FHE-Rollup, and Time-lock Encryption are all exploring this approach.

So I'd like to answer the original question again.

Why is MEV not an occasional "arbitrage behavior" but a structural phenomenon?

Because the power of ranking is an unavoidable resource allocation mechanism in all open systems. The existence of ranking is not a mistake, but a fundamental metaphor for power structures. Without addressing the governance of the power of ranking, blockchain cannot truly be "decentralized"; however, every attempt to govern the power of ranking itself creates new institutional centers and interest structures.

How does its role shift as protocol design, consensus mechanism, and on-chain economic structure evolve?

From miners to proposers, from builders to client operators, the participant structure of MEV is constantly shifting.

MEV is an "endogenous paradox" of the decentralized world.

It has put us in a dilemma: we want to eliminate it because it brings injustice and systemic exploitation; but we cannot really eliminate it because it is an inevitable byproduct of consensus mechanisms and on-chain markets.

We can only compromise, redesign, and redistribute to make it "appear controllable" under the new institutional structure.

By reflecting on MEV and confronting this mirror, we can see just how fragile and precious our so-called "decentralization ideal" truly is in the face of economic incentives and institutional realities.

The existence of the MEV game actually allows freedom to survive.

Like a shadow, through which we can see another dimension, our true selves.

Disclaimer

This article is very information-dense because many architectural overviews are highly condensed, and the technologies are not fully open source, but rather based on analysis of published information.

Furthermore, this discussion is purely from a technical solution perspective and does not imply any positive or negative evaluation of any company's products.