Compiled by: Liu Jielian

Jielian's note: The FOMC meeting of the Federal Reserve in September unexpectedly cut interest rates by about 50bp. Many self-media, experts, and financial advisors jumped out to be bullish on bonds and urged everyone to rush into US Treasuries. At that time, they presented a watertight financial common sense: when interest rates fall, bond yields will fall and bond prices will rise. Jielian has repeatedly reminded in internal references and articles to pay attention to the occurrence of "counterintuitive" situations, but still heard and witnessed many unfortunate cases. On September 18, when the Federal Reserve decided to cut interest rates, the yield on 10-year US Treasuries was 3705bp; more than a month later today, it has soared to 4224bp. In other words, rushing into US Treasuries has resulted in a loss of over 12% - for bond investments, which are generally considered relatively low-risk, a loss of over 10% in a month is quite a lot. If leverage was used, the feeling would be even more sour. A sentence that has never failed: A 100% certainty is almost certainly a money-losing opportunity. If something is bound to make money, you probably won't even know about the opportunity. And if a windfall is actively delivered to you by a financial advisor, it's probably a poisoned pie. Below, Jielian has compiled a post by netizen Porter Standsberry to reveal the truth behind the Federal Reserve's interest rate cut and the abnormal surge in US Treasury yields.

"Everyone has a plan, until they get punched in the face."

This is the situation facing Jerome Powell (Jielian's note: the current Federal Reserve Chairman), as the bond market has pushed back against the Federal Reserve's best plan to lower borrowing costs.

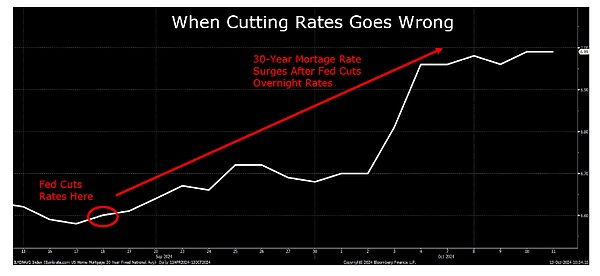

After Powell lowered the overnight rate by 50 basis points on September 18, the yield on long-term bonds such as the 10-year US Treasury actually soared by 50 basis points.

This should not have happened...

Normally, when the Federal Reserve and the market are in sync, long-term borrowing costs will follow the overnight rate set by the Federal Reserve. But when the Federal Reserve makes a policy mistake - such as cutting rates before a presidential election, even though inflation is high - the market will push back.

We've seen this before, and the ending is not good.

In 1971, despite inflation above 4%, Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns cut rates to boost Nixon's political prospects in the 1972 presidential election.

Cutting rates in the face of high inflation entrenched price pressures in the US economy. American workers, fearing continued price increases would erode their wages, began demanding higher pay.

This led to a self-reinforcing wage-price spiral, resulting in a decade of double-digit inflation, destructive interest rates, and stagnant economic growth: a toxic combination known as "stagflation".

To finally tame inflation, the Federal Reserve under Volcker raised the overnight rate to 20%.

But in the meantime, American investors experienced a "lost decade", with negative real returns on stocks and bonds. The price level of the S&P 500 in 1979 was the same as in 1968... and considering the over 50% raging inflation, stock investors lost half their real purchasing power.

Bond investors fared no better, with 10-year Treasuries losing 3% per year in real, inflation-adjusted terms, a 30% decline in purchasing power over the decade.

This was the worst decade for investor returns since the Great Depression.

In this post, I will explain why all signs point to a repeat of this situation.

Unlike stocks, which can temporarily defy economic gravity in extremely optimistic times (like today), the bond market is much more strict. For fixed-income investors, inflation is the number one enemy - this silent thief can turn positive nominal yields into negative real (inflation-adjusted) returns.

Before taming consumer prices, Jerome Powell has prematurely lowered short-term rates, repeating the fatal mistake of Arthur Burns' Federal Reserve, fueling people's fears of entrenched inflation.

Bond investors remember the 1970s. Their growing concern about the suppression of real returns by persistent inflation is now forcing them to demand a larger safety margin, causing long-term borrowing costs to soar, such as the 10-year Treasury yield.

The 10-year US Treasury is one of the most important global lending benchmarks, determining the borrowing costs for a wide range of consumer and business loans. This includes the standard 30-year US mortgage rate, which has been pushed higher by the 10-year Treasury and soared 50 basis points after Powell's recent rate cut.

This becomes a big problem, as higher borrowing costs actually further drive inflation. Especially in the housing market, high mortgage rates directly lead to higher housing ownership costs.

Currently, the monthly payment for an average-priced US home is $2,215, meaning a household income of $106,000 per year is now required to afford an average home, compared to just $59,000 four years ago (2020).

Not surprisingly, housing costs were one of the biggest winners in the September inflation report, rising 4.9% year-over-year, far exceeding the 3.3% overall inflation rate.

At the same time, the Federal Reserve's rate cut measures - which were supposed to support US economic growth - have had the opposite effect. Higher long-term rates have not lowered borrowing costs and promoted lending in the real economy, but rather the opposite.

We can see from the latest weekly data that new mortgage applications have plummeted 17%. The drop in mortgage refinancing was even more dramatic, down a stunning 26% last week.

Higher borrowing costs are not the only factor driving stubborn inflation. Insurance is another major culprit, with costs generally rising at a faster pace than the overall CPI.

For almost every American adult, insurance is a major living expense, and often legally required. Imagine the consequences if you didn't report health insurance when filing taxes, didn't have homeowner's insurance to get a mortgage, or drove without auto insurance.

Insurance companies faced significant profit losses in the early stages of post-pandemic inflation, as their previous policies were priced based on 1-2% historical inflation rates. So when soaring inflation caused claims to far exceed expectations, they had to absorb huge losses.

Now, insurance companies are starting to recoup those losses from policyholders.

Over the past few years, as old policies have expired, insurance companies have made up for their losses through steep hikes on new policies. For example, employer-sponsored health insurance plans are projected to cost 7% more for the second consecutive year - about twice the current CPI inflation rate. This is the fastest increase in over a decade, adding about $3,000 to the average family's health insurance costs just in the past two years.

At the same time, home and auto insurance premiums are also rising at double-digit rates, as experienced by those recently renewing their policies. With two consecutive destructive hurricanes expected to inflict massive losses on insurers, the industry will further raise rates to recoup those losses.

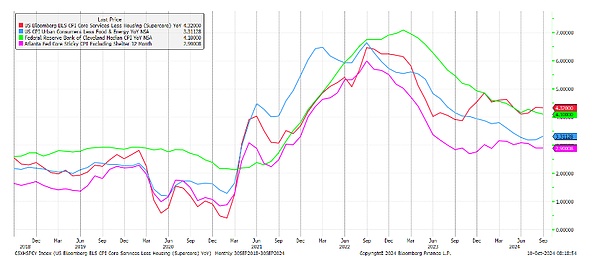

These and other stubborn costs are the reason - even excluding the volatile food and energy prices, the Federal Reserve's various "core inflation" measures have remained stubbornly above 3% since the last time CPI inflation was below 2%. And if you analyze the median price in the CPI basket, inflation has persistently hovered around 4%.

Notably, this was also the inflation floor that the Federal Reserve could not break through during the stagflation period of the 1970s.

While politicians and media pundits have done their best to make consumers believe inflation has been defeated, Americans living in the real world still feel the sting of soaring prices eroding their wages.

Now, American workers are demanding ever-higher wages to cope with the cost-of-living crisis.

For example, recently 32,000 Boeing factory workers went on strike after failing to achieve a 40% wage increase over four years. They ended the strike after Boeing agreed to a 35% wage increase over the next four years, equivalent to nearly 9% annual growth.

At the same time, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union ended its latest strike earlier this month, as the employer agreed to a 62% wage increase over the next six years, reaching an average hourly rate of $63.

With such wage increases setting the standard, it is clear that inflation is deeply entrenched in the U.S. economy, fueling the kind of wage-price spiral seen in the 1970s.

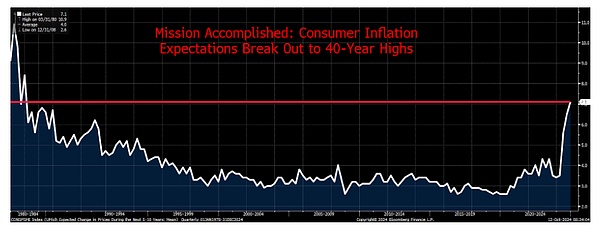

The chart below is about to become the Federal Reserve's nightmare, showing consumer inflation expectations soaring to the highest level in the past 40 years.

U.S. policymakers are repeating the mistakes of the 1970s. They have sown the seeds of a decade or more of stubborn inflation, steadily rising borrowing costs, and a "lost decade" for the U.S. economy and financial asset prices.

But this time, it may be worse. The biggest problem is that the highly indebted U.S. economy can no longer withstand the 20% interest rates needed to suppress the runaway inflation of the 1970s.

The U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio is as high as 120%, compared to 30% in the 1970s.

If the Federal Reserve simply maintains interest rates at 5% and forces the U.S. government to finance all its outstanding debt at that rate, annual interest expense will quickly approach $2 trillion. This would be equivalent to 40% of the government's annual tax revenue. If rates rise to 10%, the federal government will be forced to choose between paying Social Security and Medicare benefits and funding the military, without being able to do both.

And at 20% borrowing costs, America will officially be out of business. Uncle Sam's annual interest payments will exceed its tax revenue.

This is why all roads lead to long-term uncontrolled inflation. Raising the overnight lending rate is no longer a viable option to control inflation due to the unsustainable debt burden of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is rapidly heading towards bankruptcy, and policymakers are not even willing to acknowledge it, let alone solve the problem. Honest default and debt restructuring are clearly not viable options for politicians seeking re-election. Therefore, the only remaining choice is to default dishonestly through inflation.

But don't just take my word for it, look at legendary trader Paul Tudor Jones, who just explained today:

"All roads lead to inflation. I hold gold and , zero fixed income. The way out of this [debt problem] is through inflation."

More important than what they say is to watch the actions of the world's top investors.

Note Stanley Druckenmiller, who has just taken a massive position on long-term U.S. Treasuries. Note Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway and Ray Dalio's Bridgewater Fund, who are dumping bank stocks like outdated merchandise.

This weekend, I was told by several "keyboard finance gurus" that the problems I warned about for U.S. banks are just "a small matter." I heard the same objections when I warned about the crises facing Fannie Mae, General Motors, and more recently Boeing.

These judgments do not require any genius, just a matter of balance sheet math. The banking industry today is no different.

U.S. banks are currently facing an impaired bond investment portfolio, with losses equivalent to half their tangible equity value. If long-term interest rates exceed 10%, U.S. banks will go bankrupt.

Of course, you can hope that monetary and fiscal authorities will prevent this from happening.

But as they say, "hope" is not a strategy.[1]

1: Editor's note: This means that relying solely on "hope" is not an effective way to address real-world problems or challenges. It emphasizes the futility of hope, especially in the face of serious economic and financial crises. Hope can be inspiring, but it is not a viable method or strategy for solving problems. Effective strategies require concrete actions and plans, not just the expectation that things will improve. Therefore, the author here stresses that depending on hope without taking actual measures is not feasible.