Source: FT Chinese Website

Since being elected president, Trump has repeatedly declared that he will wield the tariff stick to solve the trade deficit problem of "stealing American jobs"; and many American politicians have also stated that tariffs will only lead to inflation.

The problem of the US trade deficit is not new, and the solutions of past presidents have varied. Economic theory tells us that the best way to reduce imports, boost exports, and reduce the trade deficit is often to devalue the currency - this will cause the prices of imported goods and services calculated in the domestic currency to rise, and the prices of exported goods and services calculated in foreign currency to fall, thereby suppressing imports and encouraging exports.

As the theory suggests, past US presidents have often viewed the devaluation of the US dollar as the panacea for solving the trade deficit problem - this story dates back to the Reagan administration. In the 1980s, when Reagan was first elected president, the US economy was suffering from severe inflation. To alleviate inflation, Reagan supported the Federal Reserve Chairman Volcker's plan to sharply raise interest rates in the double digits to tighten the money supply, and also reduced taxes to ease the burden on small and medium-sized enterprises.

Although the sharp interest rate hike lowered inflation, it also led to a significant appreciation of the US dollar. In January 1981, when Reagan took office, 1 US dollar could be exchanged for more than 200 yen; by November 1982, the peak of the interest rate hike policy, 1 US dollar could be exchanged for more than 270 yen. Although the interest rate hike policy ended in 1983, the exchange rate of the US dollar against the yen remained at a high level of over 260 yen until the end of Reagan's first term in January 1985.

The high domestic interest rates burdened the US manufacturing industry with heavy financing costs, greatly affecting its competitiveness; the significant appreciation of the dollar also allowed the manufacturing industries of Western Europe and Japan, represented by the automobile industry, to make inroads into the US market. The combination of these two factors devastated the US manufacturing industry, including the automotive industry, and the anger of the workers reached a climax. In 1982, this anger culminated in a tragedy - in June 1982, Chinese-American Chen Guoren, a resident of Detroit, was beaten to death by two unemployed auto workers.

After fixing the inflation problem in his first term, Reagan had to fix the trade deficit problem in his second term. Therefore, at the beginning of Reagan's second term in 1985, the US government launched the Plaza Accord, which allowed the yen, pound, franc and deutsche mark to appreciate significantly against the US dollar, greatly stimulating US exports to Europe and saving the US industry.

Since then, the US government has frequently used the interest rate adjustment lever to establish a "low interest rate, low exchange rate, low tariff" business model. With low federal funds rates, the interest expense on government debt is low, allowing the government to control spending; the controlled government spending also allows the government to cut taxes, reducing the burden on businesses. On the other hand, the government can borrow to build infrastructure, while low interest rates lower the exchange rate of the US dollar, promoting exports, suppressing imports, and overall stimulating domestic demand. The combination of these two factors has to some extent improved the situation of manufacturing companies.

It is said that the earth goes through a cycle every twenty years. In the past twenty years, the Chinese economy has developed rapidly, gradually replacing the position of Japan, Germany, France and the UK in manufacturing. The renminbi has also been no exception - since 2005, the renminbi exchange rate against the US dollar has steadily appreciated, from 8.3 in 2005 to 6.3 in 2013, as the US dollar has been cut and the renminbi exchange rate has been reformed. The significant appreciation of the renminbi against the US dollar has greatly improved the US trade deficit: on the one hand, Chinese people have started to travel and study in the US, and service trade exports have become an important "export" commodity for the US to China.

However, after taking office, Trump found a problem. The dollar devaluation measures used by Reagan and Obama to alleviate the trade deficit have actually led to uneven development among US states. For example, the inbound tourism that benefited from the dollar devaluation naturally benefited the states with more attractions and a more developed tourism industry; the students studying in the US benefited the states with more developed education; the procurement of agricultural products benefited the agricultural states in the Midwest. As a result, it was found that the industrial products such as automobiles in the "Rust Belt" states of the Midwest were actually difficult to benefit.

As for why the manufacturing industry is in such a sorry state, it is closely related to the Galapagosization of the US industry. Lowering the exchange rate benefits international development, but international development first requires the industry itself to have the ability to internationalize. Galapagosization precisely describes the situation where products have no competitiveness in the international market under the background of trade protectionism.

We are more familiar with the Galapagosization of Japanese society, but the US also has similar problems. For example, the US domestic automotive industry has long since abandoned the sedan industry in the face of trade protection policies for small trucks, and has instead engaged in the production of small commercial vehicles. However, the "small" commercial vehicles in the US are still too large for Europe, Japan or China - the smallest pickups in the US are often 5.5 meters long and 2 meters wide, while the vehicles used in the densely populated Europe, Japan and eastern China are often 4.5 meters long and 1.6 meters wide. In this context, the US automotive industry has long been Galapagosized, becoming a customized product that can only meet the domestic market and sell randomly in the foreign market.

But staying at home does not mean being immune to foreign competition - even in the Galapagosized market, foreign competitors can survive and develop through imitation. For example, even in the traditional "pickup" industry in the US, Japanese companies have developed products like the Toyota Tacoma to challenge the position of US companies; as for other fields, the competition from Chinese companies is countless.

At the same time, even if the demand is Galapagosized, the supply chain is often globalized. Even for products like pickups that are "domestically produced", there are often a large number of foreign components in the industry. In this context, exchange rate policy can have significant problems - under a weakening dollar, industries that rely on foreign supplies without domestic upstream industry support will naturally see their costs soar.

Against this backdrop, exchange rate policy has not worked. The Trump team can only turn to tariff barriers - unlike the broad-based exchange rate, in the view of American politicians like Trump, tariffs can "target" the final product, without affecting the import of parts.

But there is no such thing as a free lunch in this world, and those who come out to mix will eventually have to pay. As a trade protection policy, the essence of tariffs is to raise the price of imported goods to the same level as domestic goods - after all, if foreign traders lower their prices, the price with tariffs would still be lower than domestic goods, and no one would buy domestic goods. At the same time, for domestic product manufacturers, the best game strategy after the tariffs is actually to maintain existing capacity: once they expand capacity and increase market share, the government will think the problem has been solved and stop or reduce tariff subsidies.

Under the logic of "doing business with the government", domestic product manufacturers would rather raise prices for domestic goods, cry poor and lobby the government to raise tariffs to earn the extra profit from the tariff price increase, rather than improve their products and increase their competitiveness.

Therefore, the policy is constantly escalating under the "left foot on the right foot" logic of "raising tariffs - raising the price of imported goods - raising the price of domestic goods - market share first rises then falls - lobbying the government to further raise tariffs", ultimately leading to a general rise in social commodity prices. This has created the rare phenomenon of "tariff-driven inflation" - all the tariffs added have ended up on the shoulders of consumers.

To curb inflation, the FED will implement a high-interest rate policy in an attempt to ease inflation by withdrawing money. Interest rates began to rise even towards the end of the Obama administration; and during the Trump administration, interest rates continued to rise until 2019. If it weren't for the pandemic, interest rates would likely have continued to rise.

However, the high-interest rate policy has a major problem - the profit margin of the real economy is not that high.

Normally, to improve the situation of domestic voters as industrial workers, actively introduce foreign investment, and encourage domestic capital to invest directly. More investment increases the supply of local factories and "bosses", thereby giving industrial workers an advantage in their bargaining with bosses, and improving the workers' situation. This is something that any country in the world has experienced - even in the US, port workers have reaped real dividends due to the expansion of port trade.

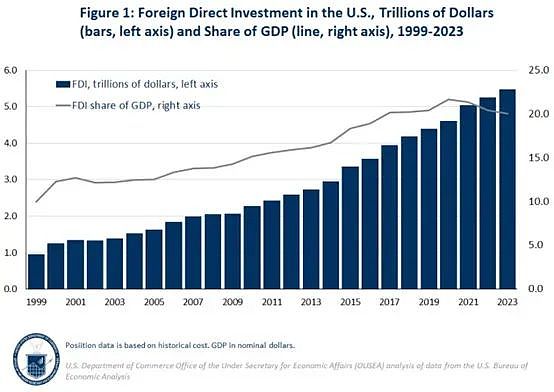

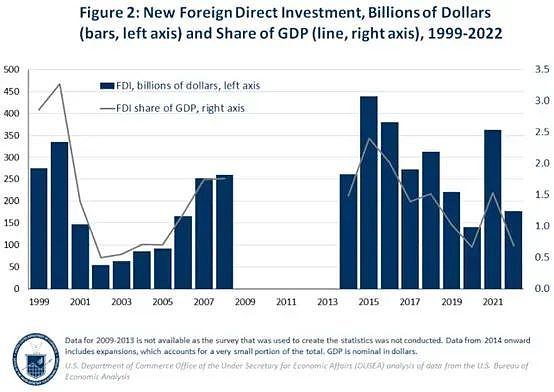

But the current situation in the US is completely the opposite: the high-interest rate policy has greatly dampened the willingness to invest in US manufacturing. Therefore, taking foreign capital as an example, although US FDI has been soaring, the capital invested in the US is mostly indirect investment (such as securities investment), and the direct investment in manufacturing has been declining year by year. If foreign capital is like this, domestic capital is even more so. Due to the lack of direct investment in manufacturing, the number of companies has not increased, and it is difficult for workers to improve their bargaining power and situation.

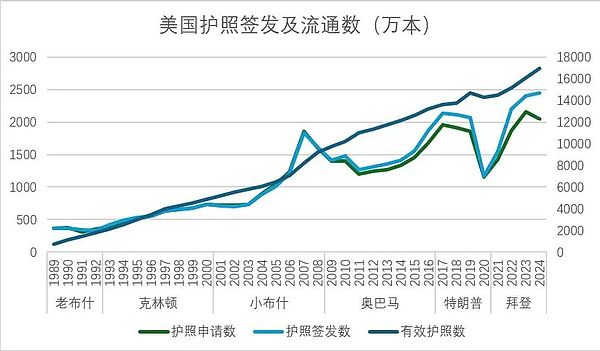

At the same time, the high US dollar exchange rate and severe domestic inflation have caused Americans to start going abroad to consume. We often hear news about Hong Kong people going to Shenzhen to consume, which is largely due to the peg between the HKD and the USD, the appreciation of the RMB, and the soaring prices in Hong Kong. As the originator, the US is certainly no exception: if you look at the number of US passports issued, you can see that the enthusiasm of Americans for outbound tourism has been soaring since the US dollar interest rate hike in 2015, and now in 2024, 25 million US passports are expected to be issued in a single year.

At the same time, the appreciation of the US dollar brought about by the US dollar interest rate hike has largely offset the effect of tariffs "raising the prices of foreign products", making the tariff policy ineffective. Although US politicians have not hesitated to call China a "currency manipulator" in the past, in reality, even if imports from China are stopped, goods will be imported from other countries (even the previously known "going through Vietnam" and "going through Mexico"), and US manufacturers have not benefited from the tariffs, but have instead suffered from the high capital costs brought about by the rise in interest rates and the outflow of demand caused by the rise in exchange rates.

At the same time, the appreciation of the US dollar brought about by the US dollar interest rate hike has largely offset the effect of tariffs "raising the prices of foreign products", making the tariff policy ineffective. Although US politicians have not hesitated to call China a "currency manipulator" in the past, in reality, even if imports from China are stopped, goods will be imported from other countries (even the previously known "going through Vietnam" and "going through Mexico"), and US manufacturers have not benefited from the tariffs, but have instead suffered from the high capital costs brought about by the rise in interest rates and the outflow of demand caused by the rise in exchange rates.

Looking back, this has become a rare phenomenon in the world - high tariffs, high inflation, high interest rates, and high exchange rates, the coexistence of these four factors in a country is really amazing and eye-opening. The only beneficiaries are probably the wealthy who rely on deposits to survive.