Event Overview

On February 21, 2025 at 02:16:11 UTC, the Ethereum cold wallet (0x1db92e2eebc8e0c075a02bea49a2935bcd2dfcf4[1]) of Bybit was drained of funds due to a malicious contract upgrade. According to a statement by Bybit CEO Ben Zhou[2], the attacker used a phishing attack to trick the cold wallet signers into erroneously signing a malicious transaction. He mentioned that the transaction was disguised as a legitimate operation: the Safe{Wallet} interface showed a normal transaction, but the data sent to the Ledger device had been tampered with to contain malicious content. The attacker obtained three valid signatures, replaced the implementation contract of the Safe multi-sig wallet with a malicious contract, and stole the funds. This vulnerability resulted in a loss of approximately $1.46 billion, making it the largest security incident in the history of Web3.0.

Attack Transaction Records

Upgrade the Safe wallet implementation contract to a malicious contract:

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x46deef0f52e3a983b67abf4714448a41dd7ffd6d32d32da69d62081c68ad7882

Multiple transactions transferring funds from the Bybit cold wallet:

- 401,346 ETH[3]

- 15,000 cmETH[4]

- 8,000 mETH[5]

- 90,375 stETH[6]

- 90 USDT[7]

Key Addresses

- Bybit multi-sig cold wallet (victim)[8]

- Attacker's initial attack operation address[9]

- Malicious implementation contract[10]

- Attack contract used in the Safe "delegate call" process[11]

Attack Process

1. The attacker deployed two malicious contracts before the attack (on February 18, 2025, UTC time).

- These contracts contained backdoor functions for fund transfers[12]

- And code to modify storage slots to achieve contract upgrades[13]

2. On February 21, 2025, the attacker tricked the three multi-sig wallet owners (signers) into signing a malicious transaction, thereby upgrading the Safe's implementation contract to the previously deployed malicious contract with a backdoor[14]: https://etherscan.io/tx/0x46deef0f52e3a983b67abf4714448a41dd7ffd6d32d32da69d62081c68ad7882

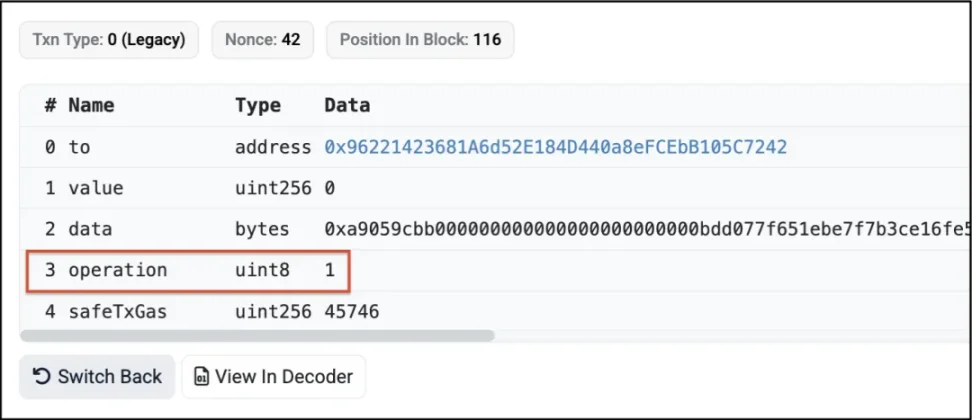

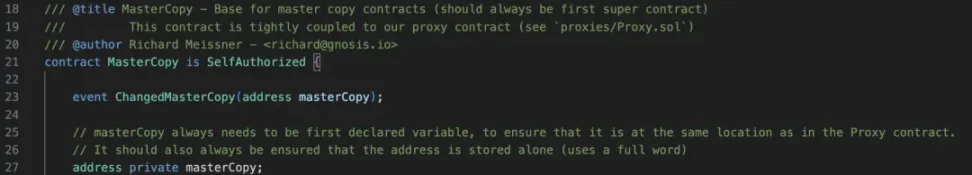

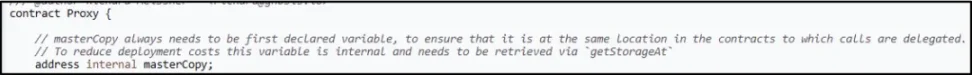

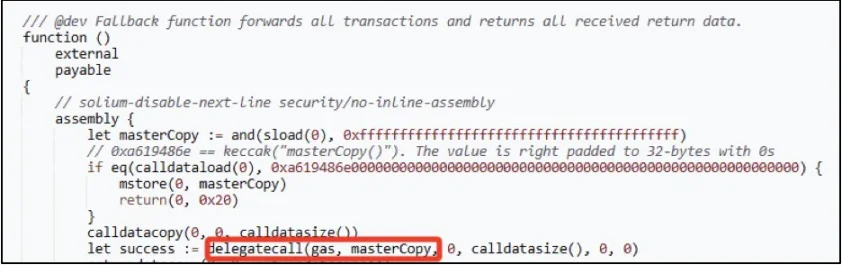

3. In the attack transaction, the "operation" field value is "1", indicating that the GnosisSafe contract should execute a "delegatecall", while "0" indicates a "Call".

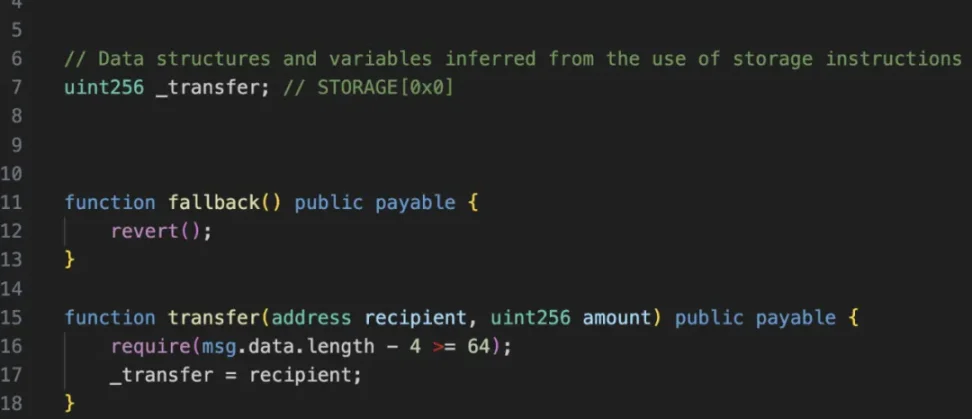

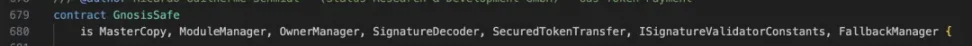

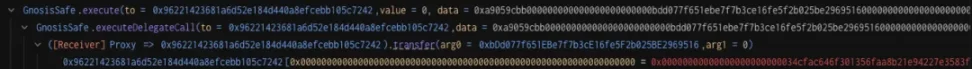

4. This transaction executed a delegatecall to another contract (0x96221423681a6d52e184d440a8efcebb105c7242[15]) deployed by the attacker, which contained a "transfer()" function that modified the first storage slot "uint256 _transfer" of the contract.

In the GnosisSafe contract, the first storage slot contains the "masterCopy" address, which is the address of the GnosisSafe contract's implementation contract.

By modifying the first storage slot of the Gnosis Safe contract, the attacker was able to change the implementation contract address (i.e., the "masterCopy" address).

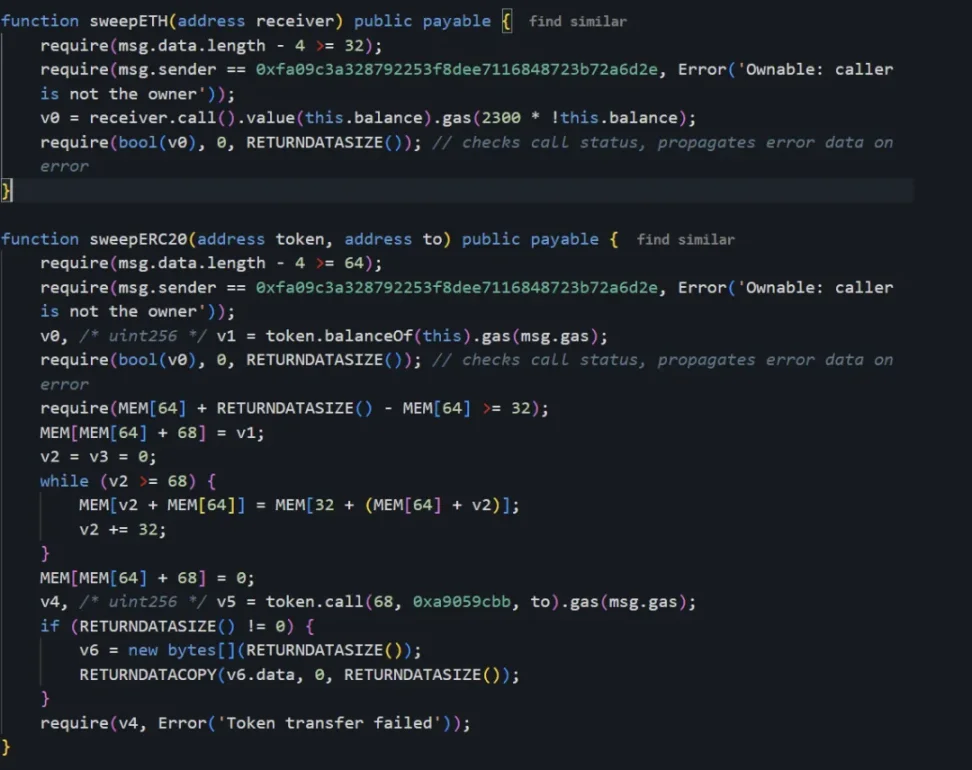

From the transaction details, we can see that the attacker set the "masterCopy" address to 0xbDd077f651EBe7f7b3cE16fe5F2b025BE2969516, which contains the "sweepETH()" and "sweepERC20()" functions described below.

5. The contract upgrade method used by the attacker was unconventional, as it was specifically designed to avoid detection of the malicious intent. From the perspective of the Bybit signers, the signed data appeared to be a simple "transfer(address, uint256)" function call, rather than a potentially suspicious "upgrade" function.

6. The upgraded malicious implementation contract[16] contained the backdoor functions "sweepETH()" and "sweepERC20()", which the attacker used to transfer all the assets from the cold wallet, ultimately resulting in the theft of $1.4 billion worth of ETH.

Vulnerability Analysis

The root cause of this vulnerability was a successful phishing attack. The attacker tricked the wallet signers into signing malicious transaction data, ultimately leading to the contract being maliciously upgraded. This upgrade allowed the attacker to gain control of the cold wallet and transfer all its funds. Currently, the specific planning and implementation details of the phishing attack are still unclear.

According to the explanation by Bybit CEO Ben Zhou in a live stream on the X platform two hours after the incident, at the time of the event, the Bybit team was executing a routine asset transfer process from the cold wallet to the hot wallet, and he himself was the last signer of the Safe multi-sig transaction. He explicitly stated that the transaction had been disguised - all the signers saw the correct address and transaction data on the Safe{Wallet} interface, and the URL had been verified by the official Safe{Wallet}. However, when the transaction data was sent to the Ledger hardware wallet for signing, the actual content had been tampered with. Ben Zhou also mentioned that he did not re-verify the transaction details on the Ledger device interface. As for how the attacker tampered with the Safe{Wallet} interface, there is currently no definitive conclusion. According to information disclosed by Arkham[17], on-chain analyst @zachxbt has submitted conclusive evidence indicating that this attack was planned and executed by the LAZARUS hacker group.

Experiences and Lessons

This incident is reminiscent of the Radiant Capital vulnerability incident on October 16, 2024 (reference 1[18], reference 2[19]), which resulted in the theft of approximately $50 million. In that incident, the attacker gained access to the developer's device, tampered with the Safe{Wallet} front-end interface to display legitimate transaction data, while the data actually sent to the hardware wallet was malicious. This type of tampering could not be detected during manual interface review or Tenderly simulation testing. The attacker initially gained access to the target's device by impersonating a trusted contractor, sending a compressed PDF file containing malware (establishing a macOS persistent backdoor) via Telegram messages.

Although the root cause of the interface tampering in the Bybit incident has not been confirmed, device compromise may be a key factor (similar to the Radiant Capital incident). Both incidents reveal two prerequisites for successful attacks: device compromise and blind signing behavior. Given the increasing frequency of such attacks, we need to focus on analyzing the following two attack methods and mitigation strategies:

1. Device Compromise:

Spreading malware through social engineering techniques to compromise the victim's device is still a major means of large-scale attacks in the Web3.0 domain. Nation-state hacker groups (such as the LAZARUS GROUP) often use this method to breach the initial defense line. Device compromise can effectively bypass security controls.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Strengthen device security: Implement strict endpoint security policies and deploy EDR solutions (such as CrowdStrike).

- Dedicated signing devices: Use dedicated devices in an isolated environment to perform transaction signing, avoiding the risks of multi-purpose devices.

- Temporary operating systems: Configure non-persistent operating systems (such as temporary virtual machines) for critical operations (like multi-sig transactions) to ensure a clean operating environment.

- Phishing simulation drills: Regularly conduct phishing attack simulations on high-risk roles (such as crypto asset operators, multi-sig signers) to raise security awareness.

- Red team exercises: Simulate attacker tactics to evaluate the effectiveness of existing security controls and strengthen them accordingly.

2. Blind Signing Vulnerability:

Blind signing refers to users signing transactions without fully verifying the transaction details, leading to the unintentional authorization of malicious transactions. This unsafe practice is widespread among DeFi users and is particularly dangerous for Web3.0 institutions managing large amounts of assets. The Ledger hardware wallet has recently started discussions on this issue (reference 1[20], reference 2[21]). In the Bybit incident, the malicious interface hid the true intent of the transaction, causing the tampered data to be sent to the Ledger device, and the signer did not verify the details on the device, ultimately leading to the vulnerability.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Avoid unverified Dapps: Interact only with trusted platforms; access official platforms via bookmarks to avoid phishing links.

- Hardware wallet double verification: Verify transaction details (recipient address, amount, function call) step-by-step on devices like Ledger to ensure they match expectations.

- Transaction simulation: Simulate transactions before signing to observe the results and verify their correctness.

- Use non-visual interfaces: Choose command-line tools (CLI) to reduce reliance on third-party graphical interfaces, as CLI reduces the risk of UI manipulation and provides a more transparent view of transaction data.

- Abort on anomaly: If any part of the transaction is anomalous, immediately terminate the signing process and initiate an investigation.

- Dual-device verification mechanism: Before signing, use a separate device to independently verify the transaction data. This device should generate a readable signing verification code that matches the data displayed on the hardware wallet.

After the multi-million dollar losses at Radiant Capital and WazirX2[22], Bybit has become the largest victim of theft in Web3.0 history. The frequency and complexity of such attacks continue to escalate, exposing significant operational security gaps in the industry. Attackers are systematically targeting high-value targets. As adversary capabilities improve, centralized exchanges (CEXs) and Web3.0 institutions must comprehensively enhance their security posture and remain vigilant against the evolving external threats.

[1] : https://etherscan.io/address/0x1db92e2eebc8e0c075a02bea49a2935bcd2dfcf4

[2] : https://x.com/Bybit_Official/status/1892986507113439328

[3] : https://etherscan.io/tx/0xb61413c495fdad6114a7aa863a00b2e3c28945979a10885b12b30316ea9f072c

[4] : https://etherscan.io/tx/0x847b8403e8a4816a4de1e63db321705cdb6f998fb01ab58f653b863fda988647

[5] : https://etherscan.io/tx/0xbcf316f5835362b7f1586215173cc8b294f5499c60c029a3de6318bf25ca7b20

[6] : https://etherscan.io/tx/0xa284a1bc4c7e0379c924c73fcea1067068635507254b03ebbbd3f4e222c1fae0

[7] : https://etherscan.io/tx/0x25800d105db4f21908d646a7a3db849343737c5fba0bc5701f782bf0e75217c9

[8] : https://etherscan.io/address/0x1db92e2eebc8e0c075a02bea49a2935bcd2dfcf4

[9] : https://etherscan.io/address/0x0fa09c3a328792253f8dee7116848723b72a6d2e

[10] : https://etherscan.io/address/0xbdd077f651ebe7f7b3ce16fe5f2b025be2969516

[11] : https://etherscan.io/address/0x96221423681A6d52E184D440a8eFCEbB105C7242#code

[12] : https://etherscan.io/address/0xbdd077f651ebe7f7b3ce16fe5f2b025be2969516

[13] : https://etherscan.io/address/0x96221423681A6d52E184D440a8eFCEbB105C7242#code

[14] : https://etherscan.io/address/0xbdd077f651ebe7f7b3ce16fe5f2b025be2969516

[15] : https://etherscan.io/address/0x96221423681A6d52E184D440a8eFCEbB105C7242

[16] : https://etherscan.io/address/0xbdd077f651ebe7f7b3ce16fe5f2b025be2969516

[17] : https://x.com/arkham/status/1893033424224411885

[18] : https://medium.com/@RadiantCapital/radiant-post-mortem-fecd6cd38081

[19] : https://medium.com/@RadiantCapital/radiant-capital-incident-update-e56d8c23829e

[20] : https://www.ledger.com/academy/topics/ledgersolutions/what-is-clear-signing

[21] : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-O7aX6vUvs8

[22] : https://wazirx.com/blog/wazirx-cyber-attack-key-insights-and-learnings