Author: Dr_Gingerballs, encrypted Kol

Source: Dr_Gingerballs X account

Compiled by: zhouzhou, BlockBeats

Editor's Note: This article analyzes the abnormal impact of the Fed's rate cut on bond yields, with the core view being that in the current environment, the Fed's rate cut will lead to a decline in short-term interest rates, but due to the massive debt and deficit, the market will demand higher yields on long-term government bonds to maintain the balance of the investment portfolio. In addition, the operations of the Fed and the Treasury have inadvertently transferred public wealth to asset holders, and the economic recession will exacerbate this problem.

The following is the original content (edited for easier reading):

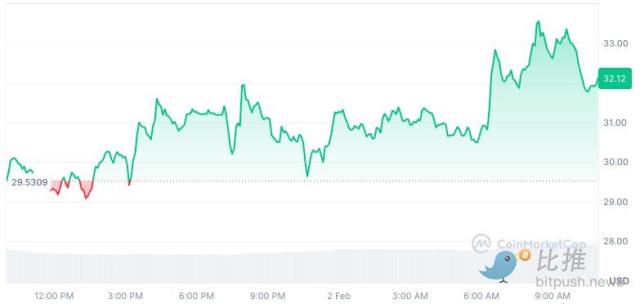

Tomorrow is a critical day for the Fed, with many expecting a 25 basis point rate cut. After the last 50 basis point rate cut, bond yields rose sharply, which did not surprise me. So why would the Fed's rate cut in 2024 lead to a rise in bond yields?

To be concise and clear, I have designed a chart to illustrate my point most intuitively. The chart shows the annual deficit growth rate in the US and the total interest paid on the existing national debt (data directly from the Treasury website). Note that before 2008, the US debt-to-GDP ratio was maintained at 40-60%, meaning that the private sector (banks) could issue a large amount of currency relative to the public sector, and the funds could be used to purchase new debt without worrying about the proportion of government debt in the investment portfolio. In fact, issuing government bonds to provide high-quality assets for the market to hold was beneficial.

But in 2008, the "original sin" of the Fed occurred, and Pandora's box was opened. Faced with a sharp drop in tax revenue, the government spent a large amount of funds, which the Fed monetized through quantitative easing (QE). People were concerned that this would lead to inflation, but surprisingly, inflation did not occur. This laid the foundation for the government's large-scale spending without consequences. So the Fed can buy our debt, maintain low interest rates, and there is no inflationary punishment? "Free money"!

The government has indeed spared no effort to spend. From 2009 to 2013, debt rose from 60% of nominal GDP to 100%, and has remained so until 2020. Many have forgotten that we actually had some inflationary issues even before the pandemic, and the Fed was then raising interest rates. By exporting inflation abroad, the benefits we have gained are gradually disappearing. Looking back, we have been stepping into dangerous territory.

In 2020, a new money printing plan began, further confirming the end of our "free money" era. When the Fed monetized these expenditures, inflation soared quickly. There is no more QE without triggering inflation.

So what did the Fed do? They stopped printing money, while the Treasury continued to issue debt. That is, the Fed no longer buys these government bonds, which means they must be absorbed by the private sector.

Omitting some details, essentially, the Fed and the Treasury have created an environment in which they reward debt holders by raising short-term interest rates and concentrating all debt at the short end. For government bond holders, this is good, as they can purchase these additional debts, obtain cash flow, and bear lower term risk. This is equivalent to "more free money".

It is worth mentioning that this "free money" is a process of transferring wealth from the public to asset holders (the rich). The Fed's raising of interest rates and the Treasury's reduction of term risk are intentionally directing funds from the poor to the rich. The deficit is borne by everyone, but the interest on government bonds only benefits a few.

But there is a problem. The Treasury must issue a large amount of debt, which means it must be purchased by the private sector (as the Fed will not risk inflation by buying it). But the private sector wants to maintain a specific proportion of bonds in its investment portfolio. The only way to avoid government bonds gradually occupying the entire investment portfolio is interest payments.

This brings us to the crux of my chart. In an environment where investment portfolio allocation determines valuation, portfolio allocation is relatively rigid, and overall, bond holders will only buy more bonds if they are compensated with cash flow. The result is that the interest payment on the existing debt must be balanced with the speed of new debt issuance.

The conclusion is simple: government bond interest payments must equal the new debt issuance rate. Currently, the deficit growth is about 6%-7% of nominal GDP, so bond yields must rise to 6%-7% to achieve balance. But remember that if the private sector grows fast enough, some of that money creation can be used to lower bond yields.

Okay, back to the Fed. In an environment where interest cash flow is king, what happens if the Fed lowers the short-term Treasury yields that the Treasury is concentrated on? The short-term interest payment will drop significantly. So what will the market do to maintain the portfolio allocation? It will demand higher long-term rates.

Therefore, the first-order effect of the Fed's rate cut must be to push up rates in other places to meet the cash flow needs of bond holders. So we are in a strange world where rate cuts will cool the economy (the economy depends on long-term maturities), while rate hikes will stimulate the economy.

I fully expect the Fed to cut rates tomorrow, and I also expect the long end of the yield curve to continue rising, with bond holders demanding returns from their portfolios. Counterintuitively, an economic recession will only make this problem worse, as the private sector cannot naturally absorb these bond issuances. Instead, a thriving economy will keep rates at a reasonable level.

I don't envy those who have just been elected into this predicament, as I'm almost certain they are unaware of these circumstances. Everything will seem fine until it suddenly becomes very bad.