Thanks to Barnabé Monnot, Caspar Schwarz-Schilling, Charles St. Louis for feedback on this post.

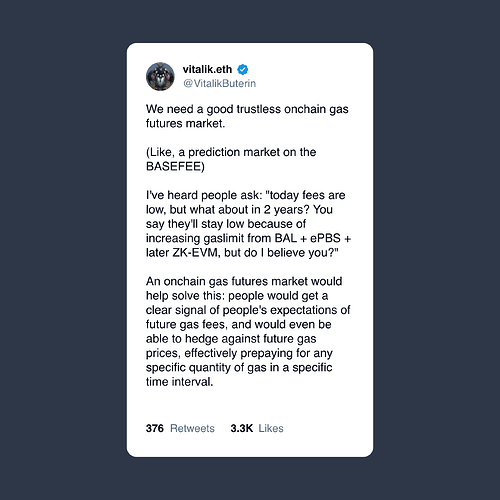

Blockchain users must pay gas fees to transact. Variation in gas fees leads to bad UX. Users of Ethereum need to have funds set aside in case fees spike and businesses take fee volatility into account when deciding where to deploy. These problems are very real and have come up repeatedly over the years: Ed Felten, founder of Offchain Labs and Arbitrum, mentioned fee volatility as a problem for L2s in a talk in 2022, and Barnabé Monnot describes the problem around the same time. Arc, Circle’s planned chain, Arc, argues price volatility is exacerbated by ETH price volatility. Finally, Vitalik’s recent tweet inspired this post:

Markets for future blockspace are clearly desirable. Many parties have tried to structure a product to achieve it. I have chatted with around a dozen individuals and companies that tried to launch such a product. Still, we don’t have it today. In my 2022 posts on structuring blockspace derivatives (here and here), I point out two main reasons why these products are hard to create:

- The majority of the gas fee proceeds, the base fee, is burnt. No party will receive base fees in the future, as a result, no party that has a natural long position on gas futures. Therefore, only speculators can supply the short side of gas futures. Because the base fee is burnt, gas futures only shift risk from one party to another instead of reducing overall risk.

- The base fee is manipulable. EIP-1559 sets a rule that determines the next-slot base fee price based on the current slot’s gas usage. Holders of gas futures could manipulate the base fee to their benefit.

In this post, we explore how EIP-1559 is the core cause of these problems and sketch a possible solution. In summary, EIP-1559 and gas futures are two mutually exclusive tools that try to solve a similar issue: improving predictability of fees. EIP-1559 does so for the current slot whereas gas futures would do so for any slot. To allow gas futures, Ethereum would need to remove EIP-1559 and create in-protocol gas futures market. The main contribution of this post is a sketch for such an in-protocol gas futures market.

Incompatibility between EIP-1559 and Gas Futures

Gas futures require a buyer and a seller. There is clear buyer demand for these products as mentioned before. L2s would want to buy blob futures, users, dapps, and wallets may want to buy regular gas futures. The problem is that there is no seller of these financial products because no single person receives the gas fees, instead they are burnt. Speculators would need to step in to provide these products which has not happened yet despite repeated attempts.

Perhaps you could even prove that EIP-1559 and gas futures are incompatible. We attempt to do so, very informally, with a proof by contradiction. EIP-1559 satisfies three properties: users pay no more or less than the base fee, proposers accept any transaction that pays the base fee, and users and proposers cannot profitably collude. For those familiar with Tim Roughgarden’s paper related to EIP-1559, these properties are DSIC, MMIC, and OCA-proofness respectively.

Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that base fee futures exist. There is a holder of the future who paid some price for it previously and will now receive some amount of blockspace at no additional cost. The seller of the derivative was previously paid by the buyer and must pay for the blockspace today.

Consider the special case in which the proposer is the holder of the base fee future. You can interpret this as the case in which base fees are not burnt but given to the proposer. Normally, the proposer would not accept a transaction that pays less than the base fee. However, if it’s also the holder of the base fee derivative, it could sell the base fee derivative to the marginal user even if their maximum willingness-to-pay is less than the base fee.

By selling the gas future to the marginal user, the proposer at least gains the marginal user’s willingness-to-pay which is higher than zero even if lower than the base fee. This is a profitable collusion between the proposer and user to include a transaction below the base fee price, breaking Roughgarden’s OCA-proofness, and therefore the base fee.

Even if not the proposer, but some other entity holds the base fee future, the holder could sell to a user who wants to include their transaction for some value. The sale happens even if the price is below the base fee. Therefore, a functional base fee derivatives market would defeat EIP-1559’s properties, but today EIP-1559 prevents a functional base fee derivatives market.

To create a functional base fee derivatives market, I believe EIP-1559 must be materially changed. Ethereum could go back to a first-price auction as it had before EIP-1559 was implemented. Then proposers know they will receive the gas fee proceeds and could be sellers of gas futures. There are two problems with this: First, it depends on proposers opting in to becoming gas futures sellers. Ensuring the market has large proposer adoption is a difficult cold-start problem. Secondly, the futures could only be sold up to about 13 minutes in advance as it is unknown who would be the proposer before then. Such a market would not provide certainty to builders deciding where to deploy their application. For a proper gas futures market, Ethereum needs to implement it into the protocol itself.

In-Protocol Gas Futures

In this section, we assume for simplicity that no in-protocol transaction fee mechanism exists and sketch how a gas futures market may work. In the last section we discuss the interaction between a transaction fee mechanism, which allows regular users to submit transactions, and the futures market.

An in-protocol gas futures market has three phases.

- Primary Market. Futures for gas units of slot NN must be initially sold from the Ethereum protocol to users, for example, in slot N-kN−k.

- Secondary Market. Participants who bought futures in the primary market may want to trade gas futures, we call this the secondary market. The protocol must keep track of who the futures holders are.

- Settlement. The gas fee future holder must be given access to blockspace.

We sketch how these three phases may look.

Primary Market. Futures must initially be sold in slot N-kN−k. The sale could occur via a system contract on the execution layer. Potential buyers send orders with the form (bid_per_gas, units_of_gas) where bid_per_gas is the amount of ETH the user is willing to pay per unit of gas future they receive and units_of_gas is the amount of gas they want to receive. The system contract then runs an auction to allocate to the highest bidders.

Secondary Market. When the futures have been issued and have initial holders, they can start freely trading. Two things that may need to be tracked during trading are 1) public keys of holders and 2) market price per unit of gas. Public keys of holders allows the system contract to deliver the inclusion list proposing rights. This is in principle only necessary at the end so instead of continuously tracking this as holders change, it could be possible that holders are only updated just before block NN. The market price per unit of gas may have to be tracked in-protocol to help a transaction fee mechanism as described in the Other Considerations section.

Settlement. Holders of gas futures must receive access to blockspace for the units of gas their futures represent. Ethereum could provide physically settled gas futures by giving future holders access to blockspace for the units of gas they hold futures for. This could for example be done by giving a holder of 10M worth of gas futures the right to propose an inclusion list of 10M units of gas. This is similar to the IncluderSelect proposal which allows people to buy the right to become an includer in FOCIL. IncluderSelect works by letting anyone send an execution layer transaction that specifies how many units of gas the user needs and how much they are willing to pay per unit of gas. A system contract takes these bids as inputs and outputs which users receive what size inclusion list proposing rights.

Other Considerations

The goal of this post is to get a temperature check on whether Ethereum may consider a drastic change to its transaction fee mechanism from EIP-1559 to a gas futures market. It leaves important details like the auction settlement out of scope. Still, we highlight some important future considerations here.

Spot Transaction Inclusion. To buy futures in both the primary and secondary market, buyers must be able to get their transactions on-chain. More generally, many users today do not care to hedge against gas fee volatility and may want to send their transactions to the public mempool for inclusion as they do today. To allow both regular users and futures buyers to interact with Ethereum, it may be necessary to sell less gas fee futures than there is gas in the block. For example, if the gas limit is 60 million gas units, 30 million could be sold in a futures market and the other 30 million could be filled up with regular user demand. Ensuring that the prices for both forms of inclusion are in tandem with each other is a hard problem that requires careful transaction fee mechanism design.

Why futures? Users may want to hedge their exposure to gas fees via other instruments than futures. I believe offering standard futures is the best fit for Ethereum though since it matches the delivery via inclusion lists. Moreover, offering futures in the primary market allows traders to structure different products in the secondary market. It is a well-known result of finance, the put-call parity, that with futures it is possible to construct other financial derivatives like put and call options.

Squatting and Allocative Efficiency. A goal of Ethereum’s transaction fee mechanism is to ensure that the users that value blockspace the most receive it. When selling blockspace far in advance, it may be allocated to someone who valued it the most a year ago but does not do so anymore today. That is, the allocative efficiency of blockspace goes down. In the worst case, someone may simply not use their blockspace (i.e. someone may squat) and Ethereum throughput would be decreased. A decrease in allocative efficiency is inherent to gas fee futures. What Ethereum loses in allocative effiency it gains in investment efficiency. People are more likely to invest in building on Ethereum if they are ensured they can access blockspace in the future.

Unconditional Inclusion Lists. FOCIL is currently suggested with conditional inclusion lists. That means that if the block is full, inclusion list transactions may be excluded. If inclusion lists are sold far in advance as a means to hedge against gas volatility, the inclusion list should become unconditional. Unconditional inclusion list transactions must be included in the block and have priority over others if the block is full.